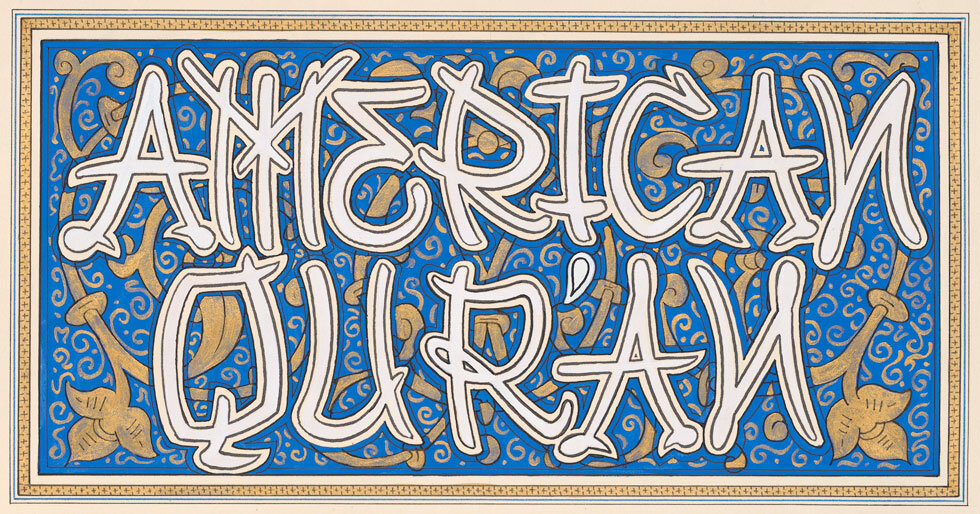

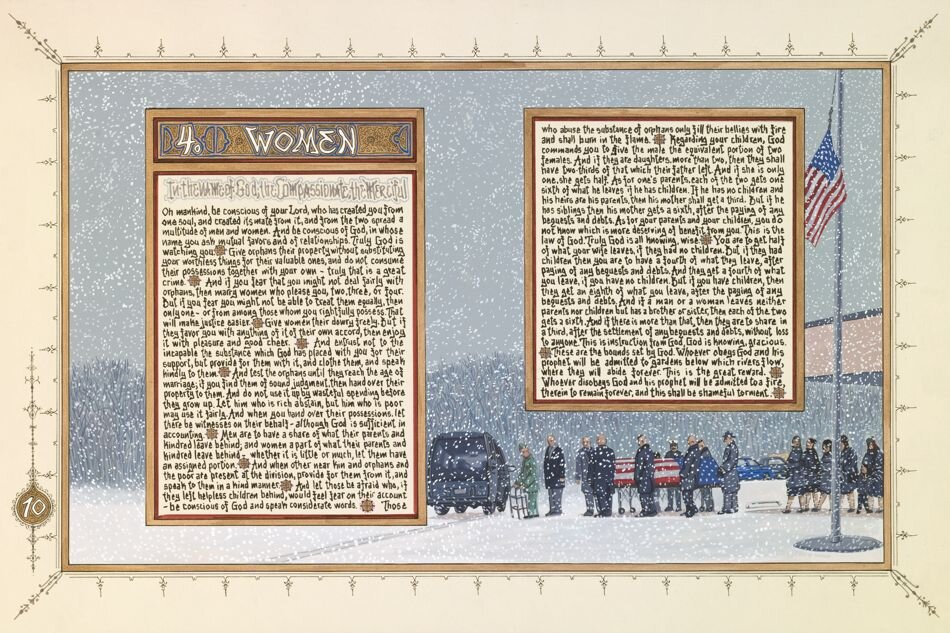

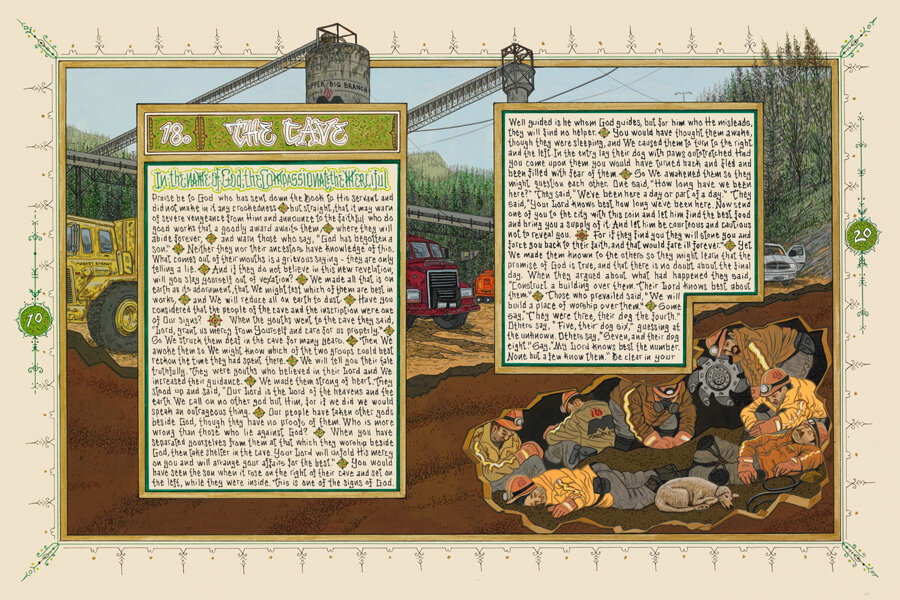

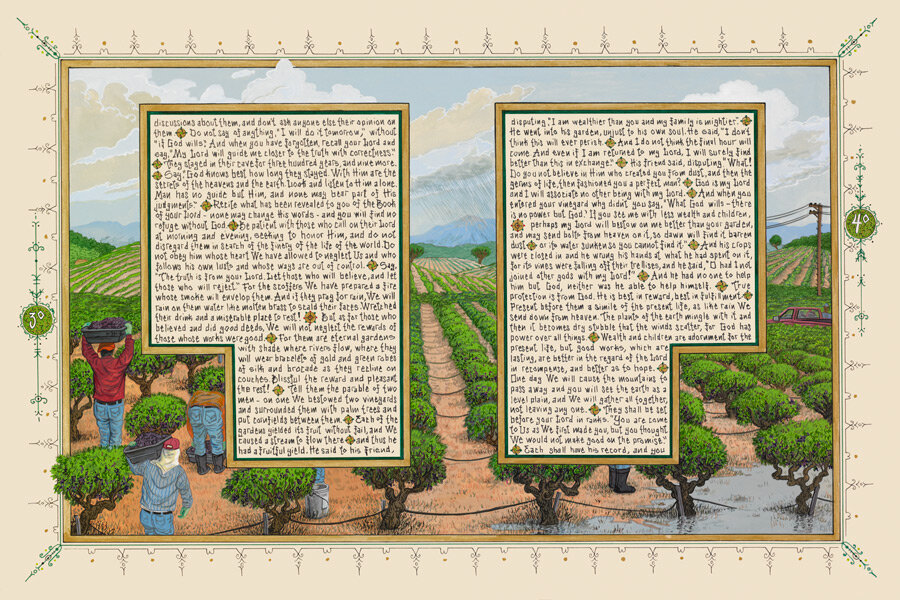

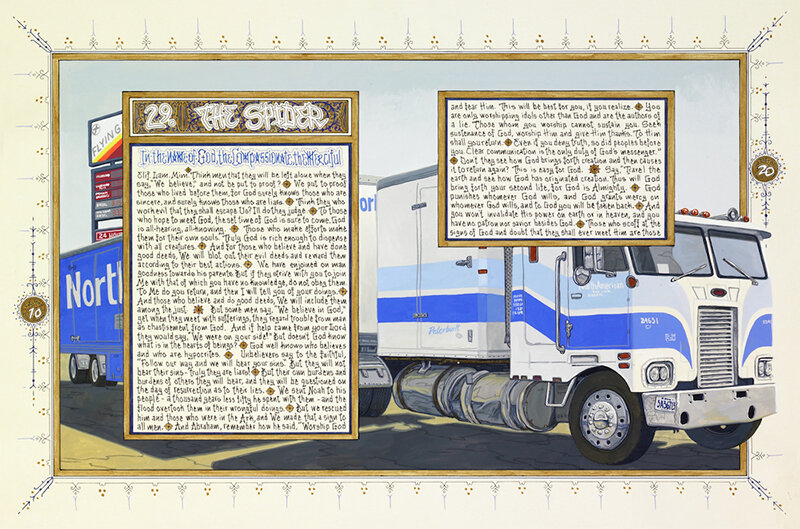

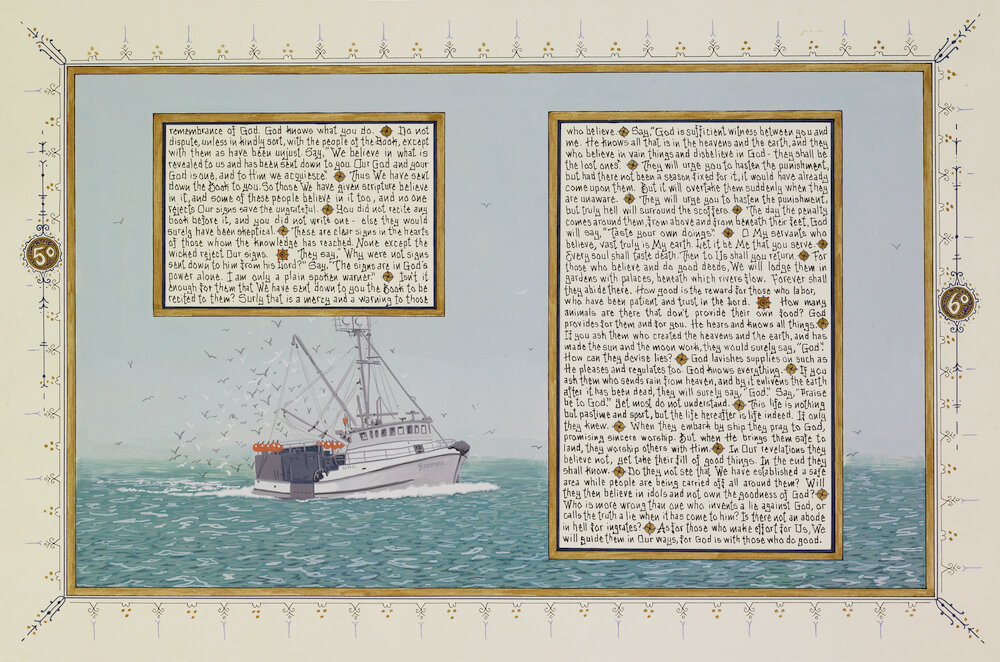

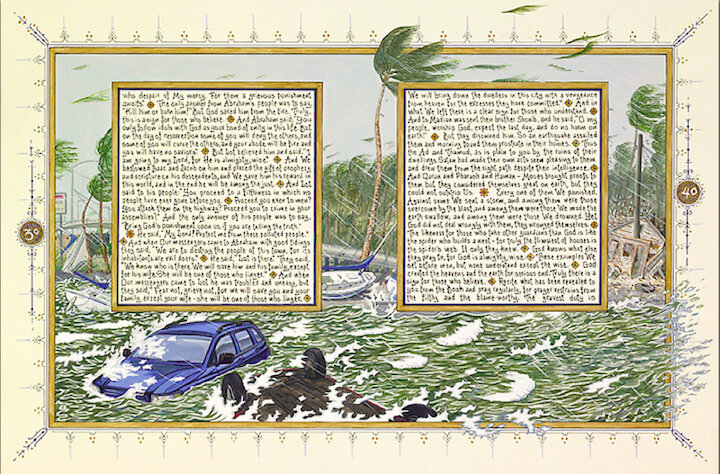

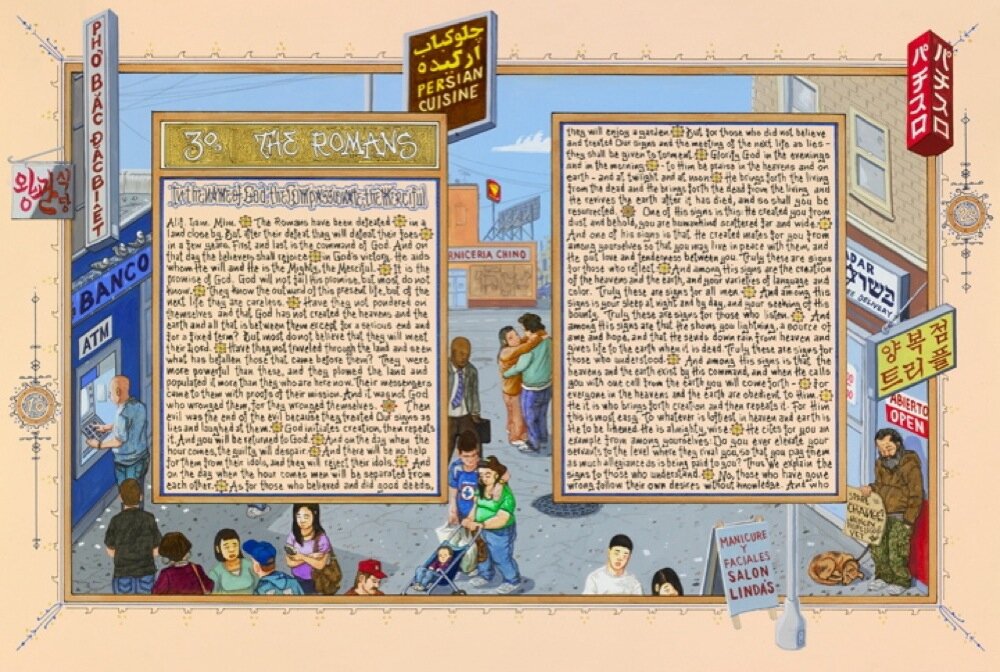

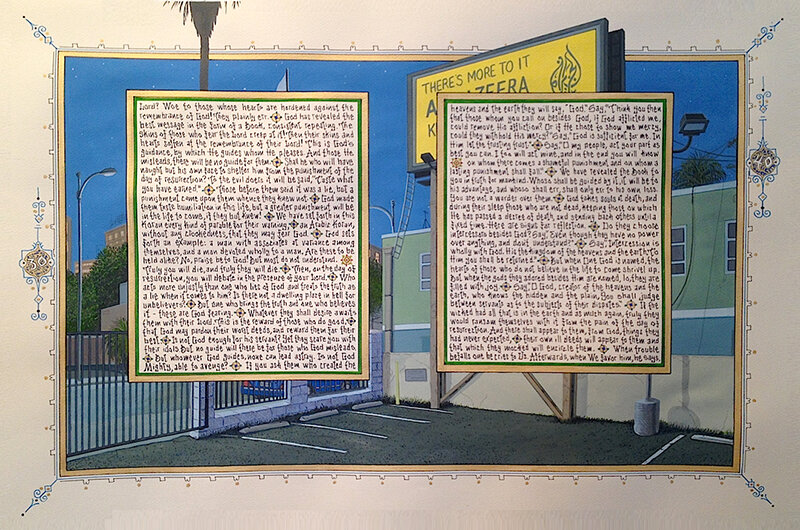

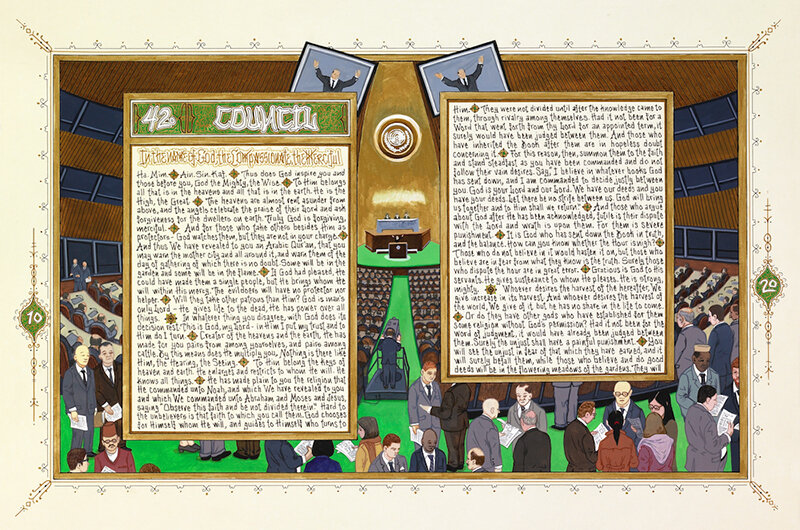

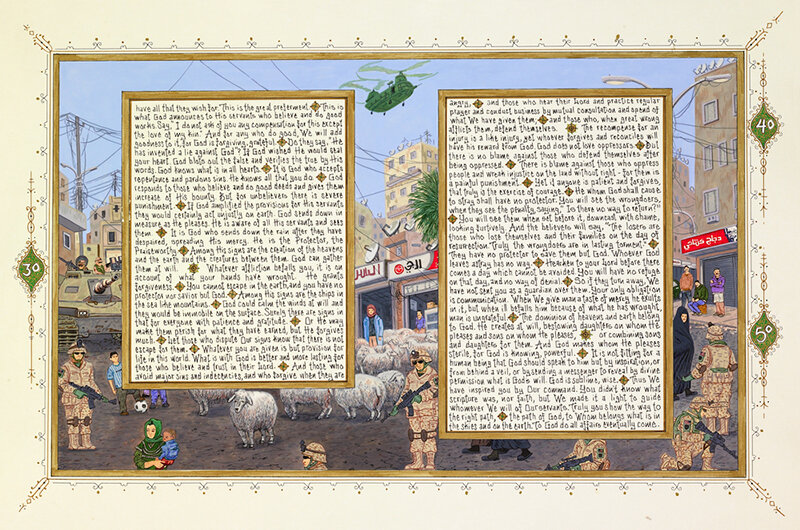

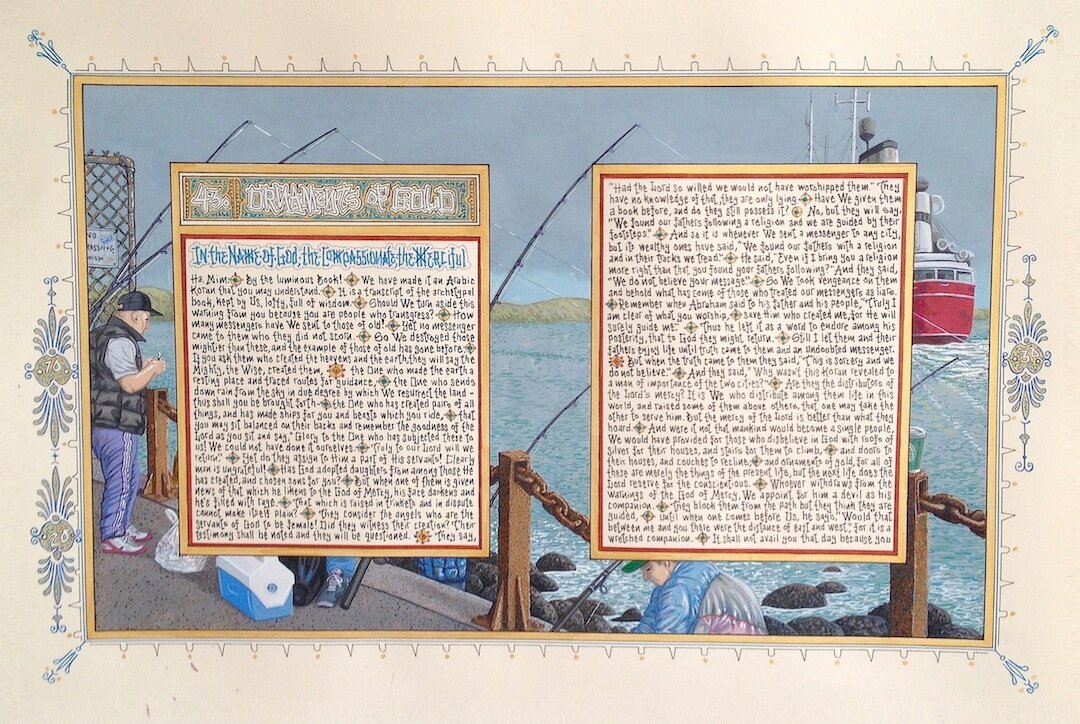

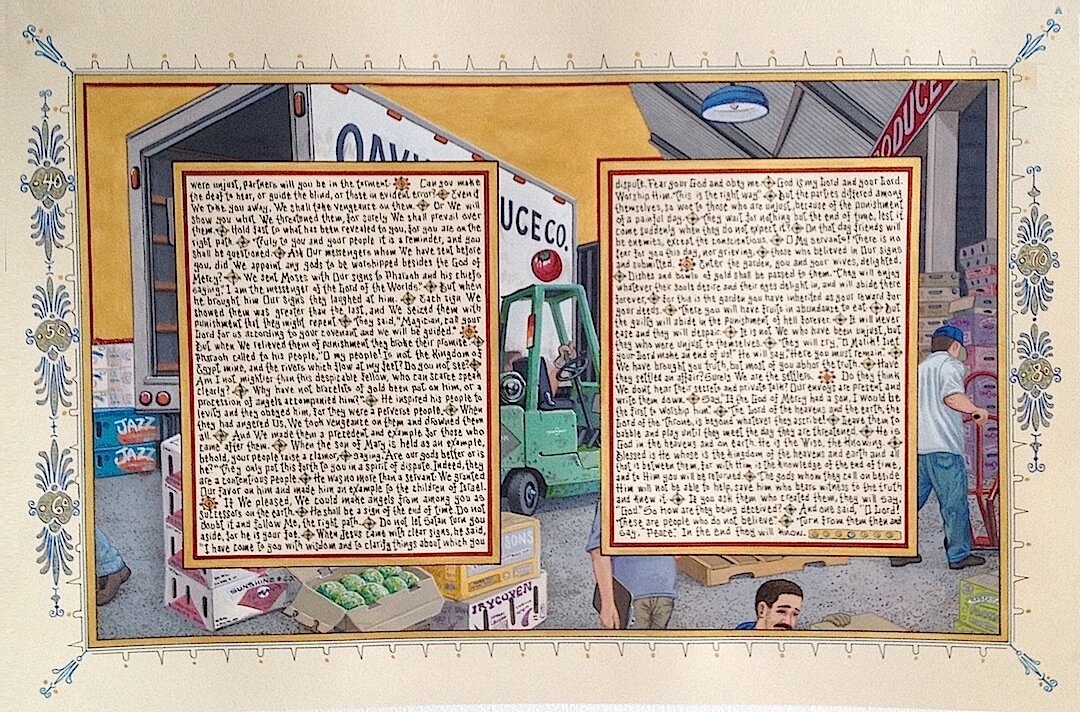

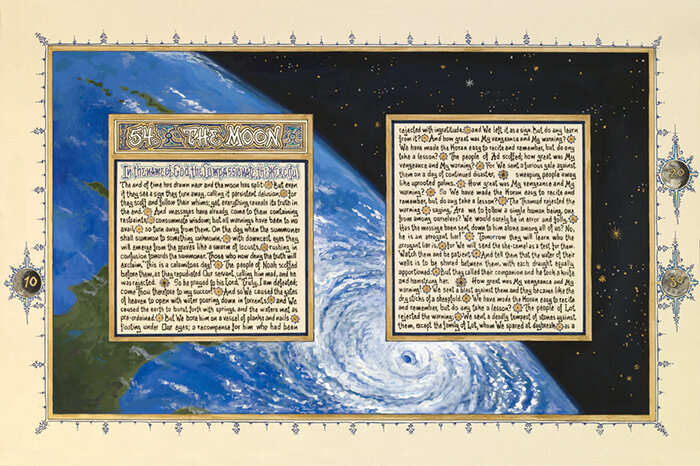

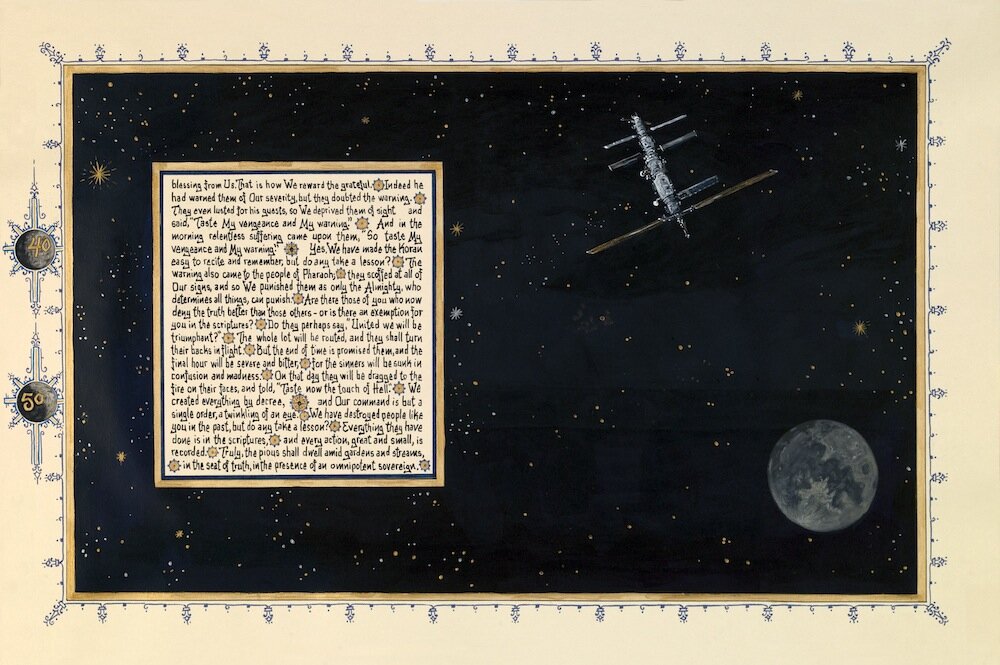

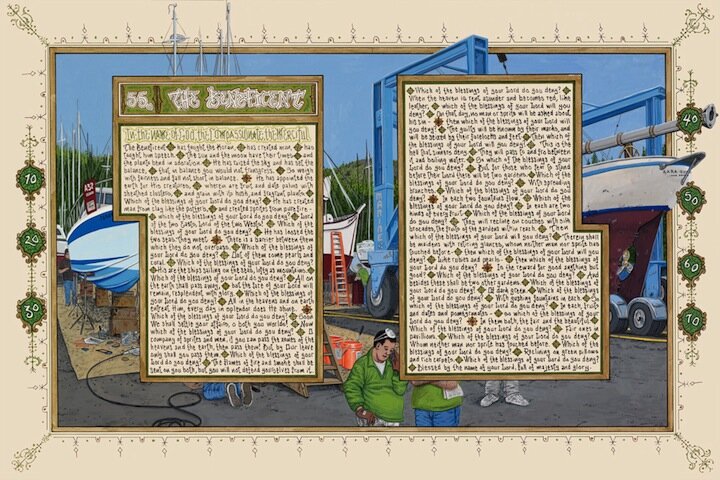

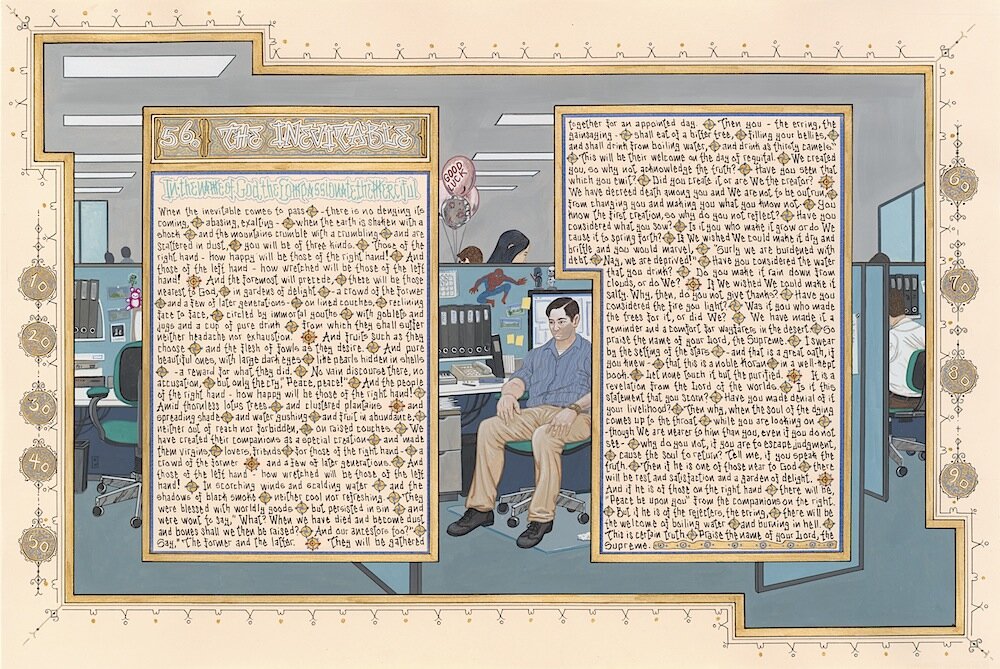

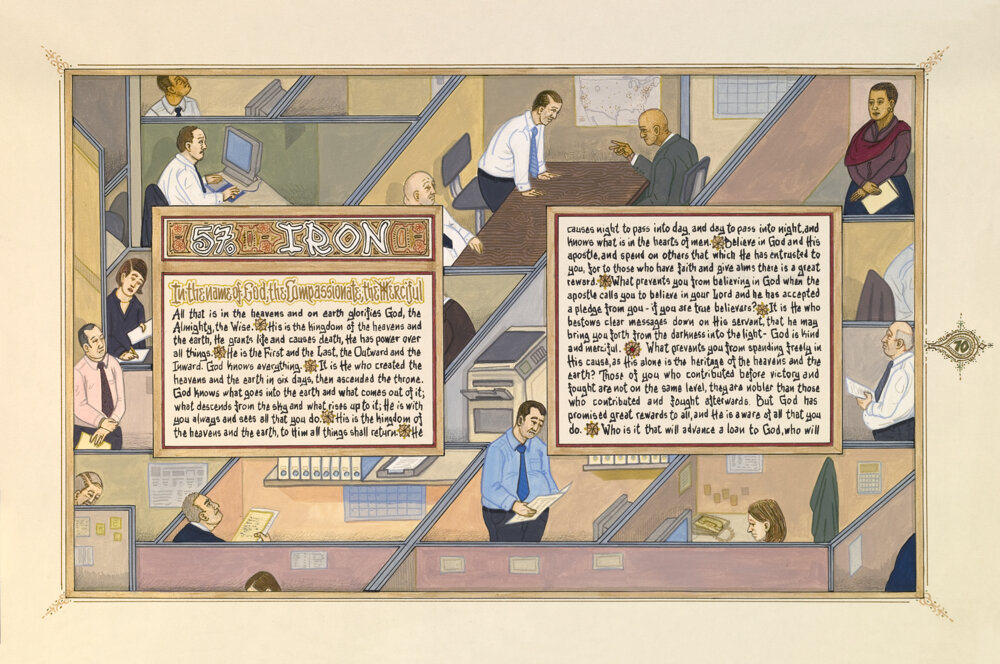

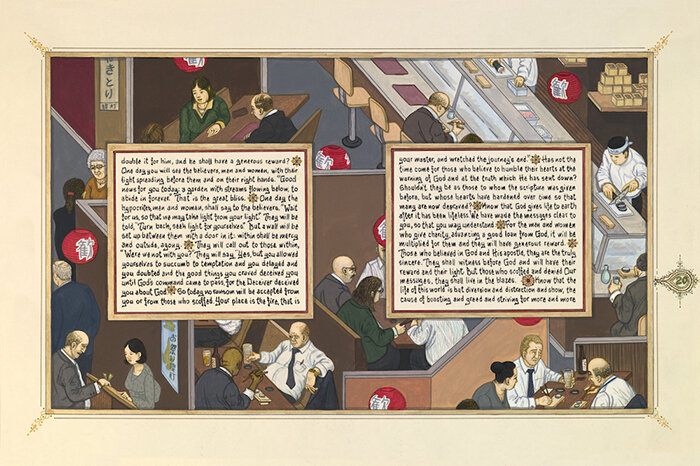

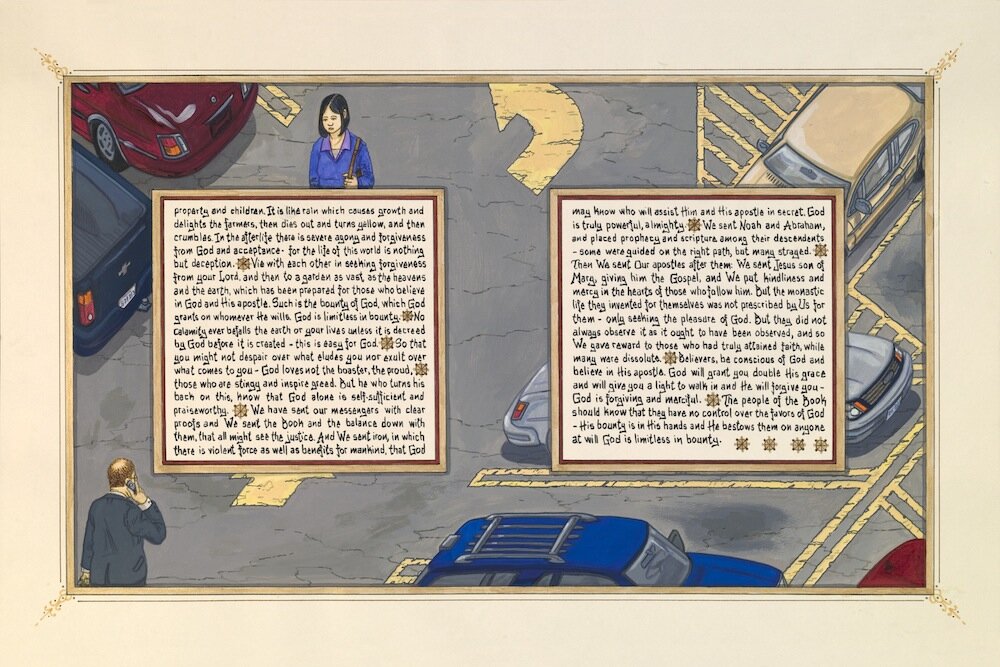

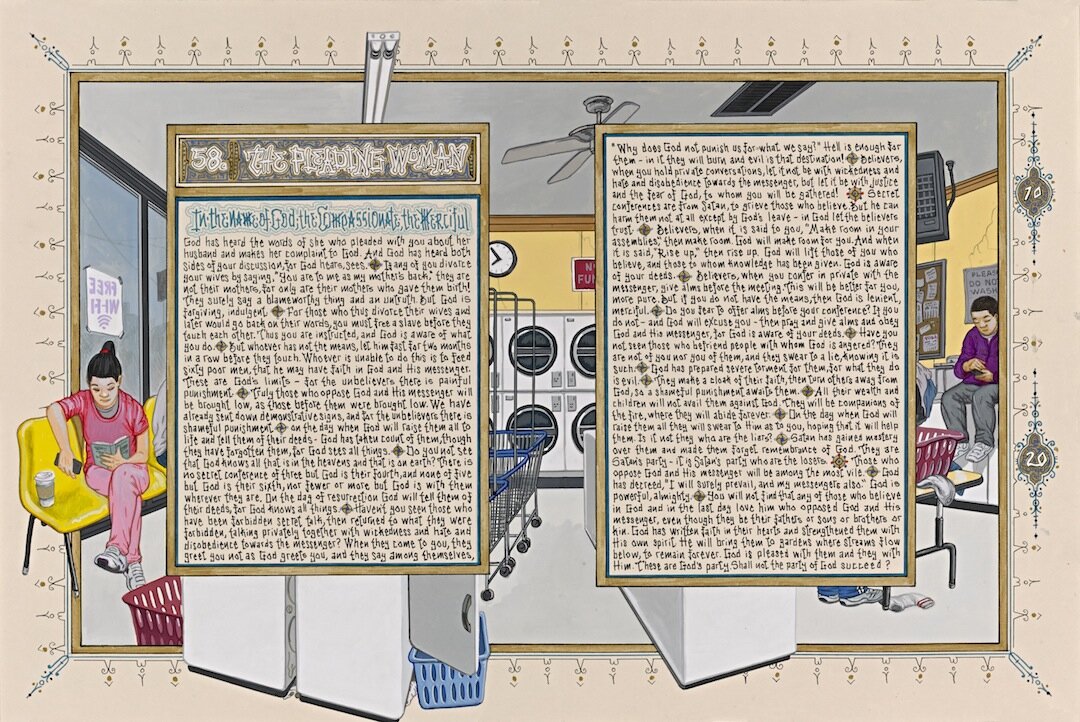

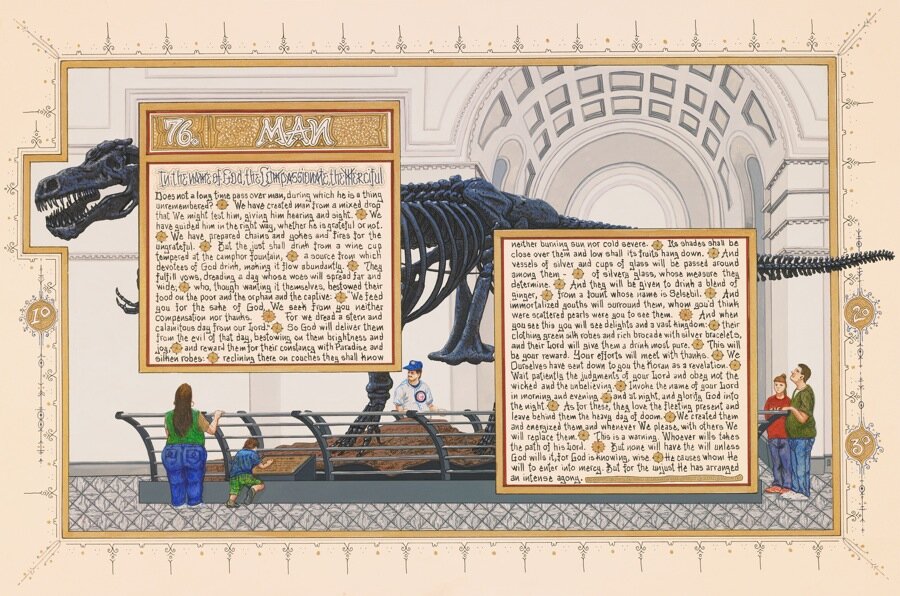

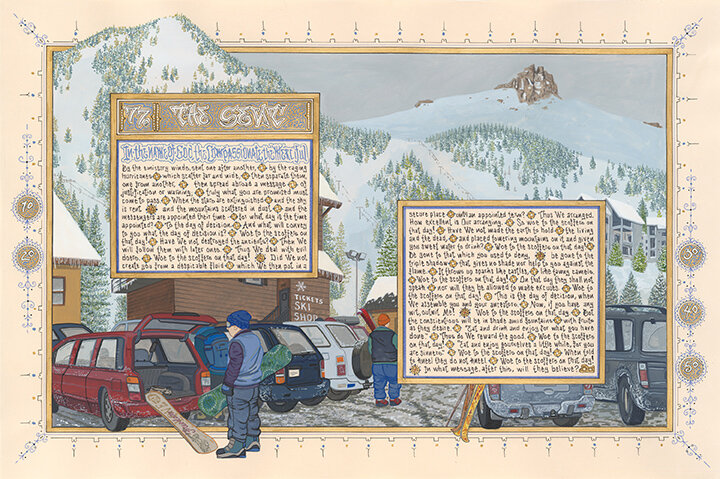

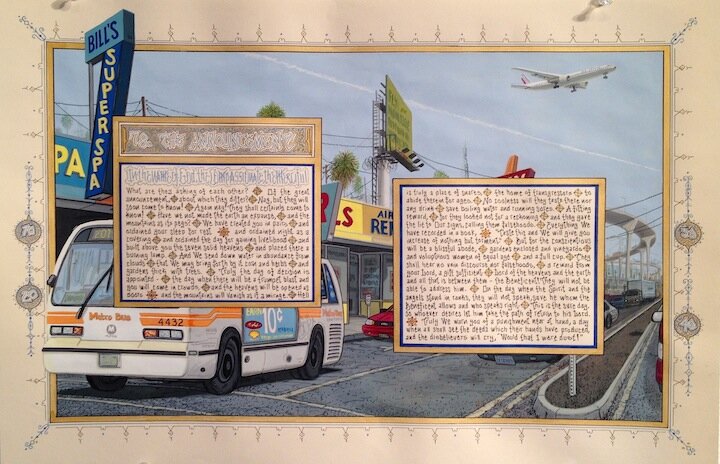

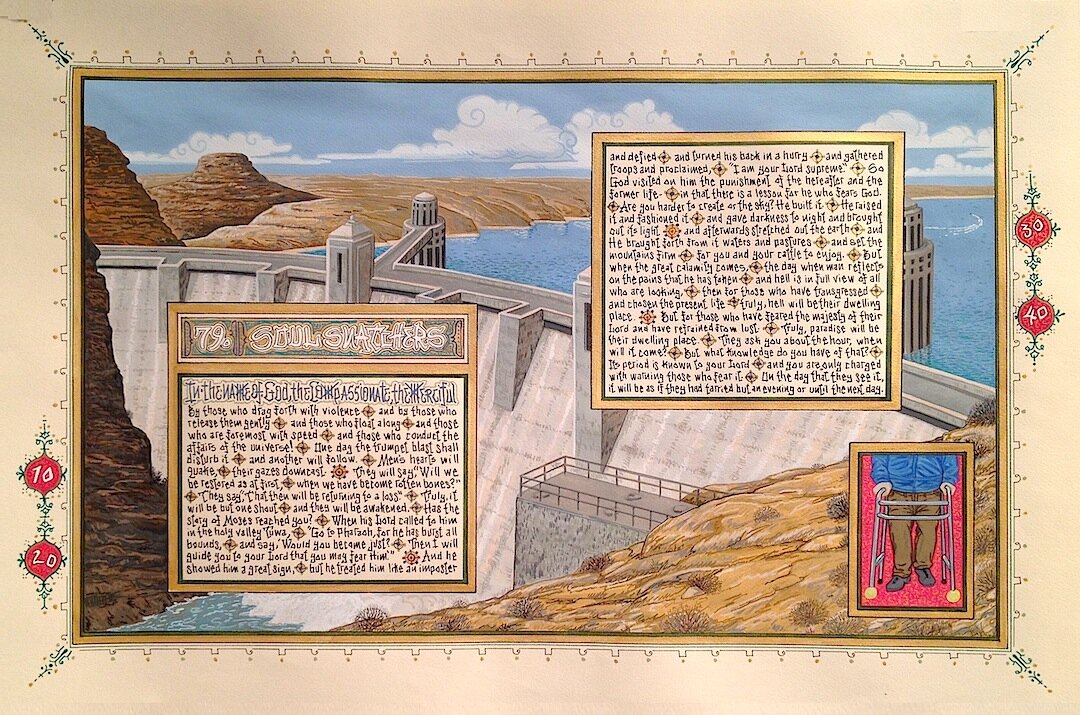

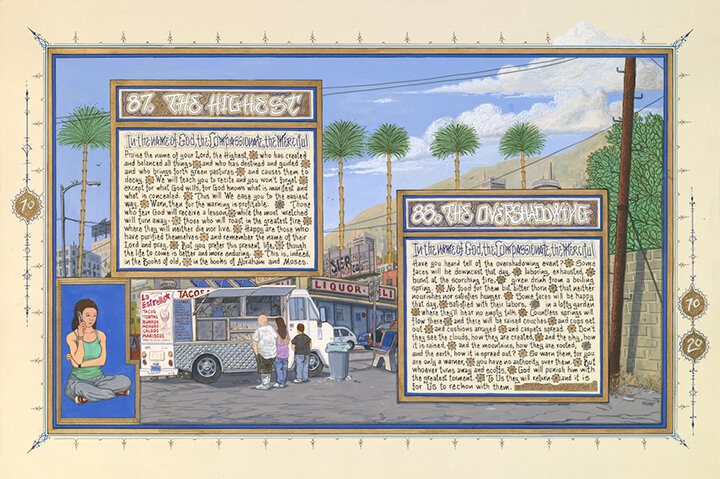

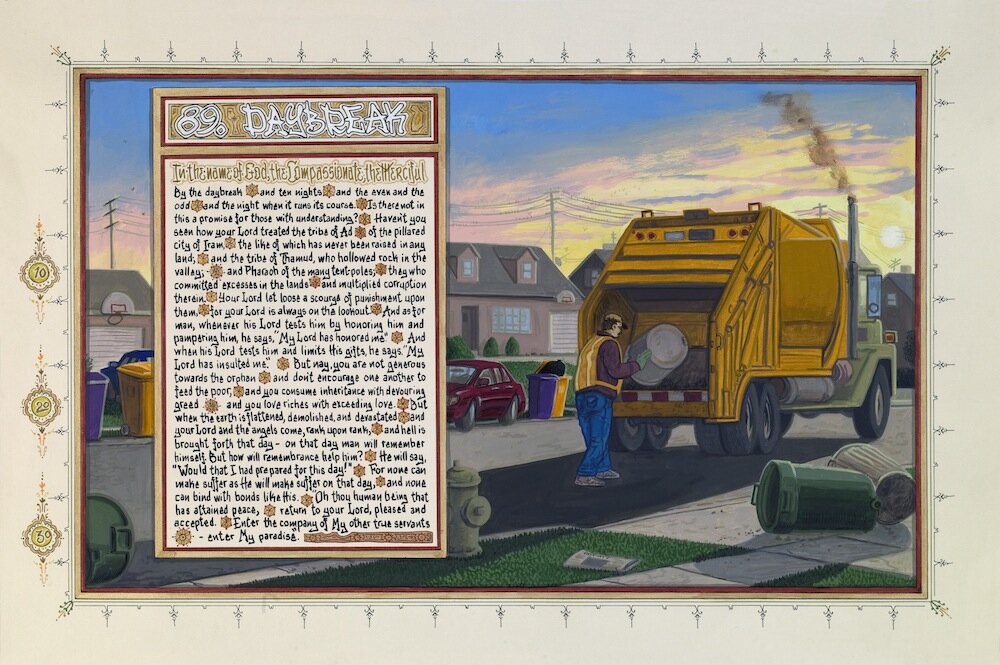

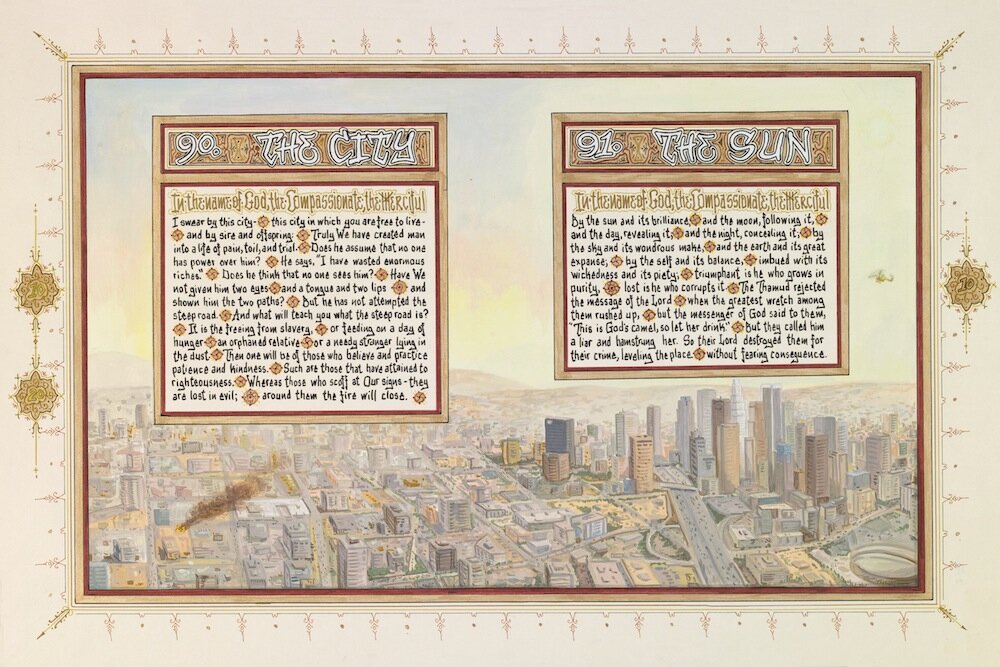

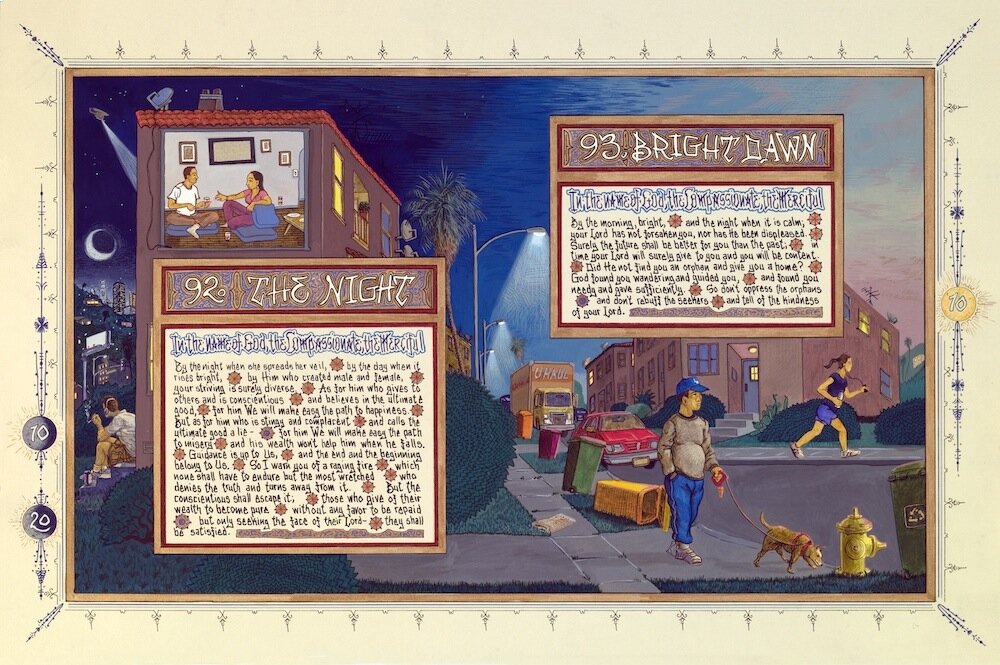

American Qur'an

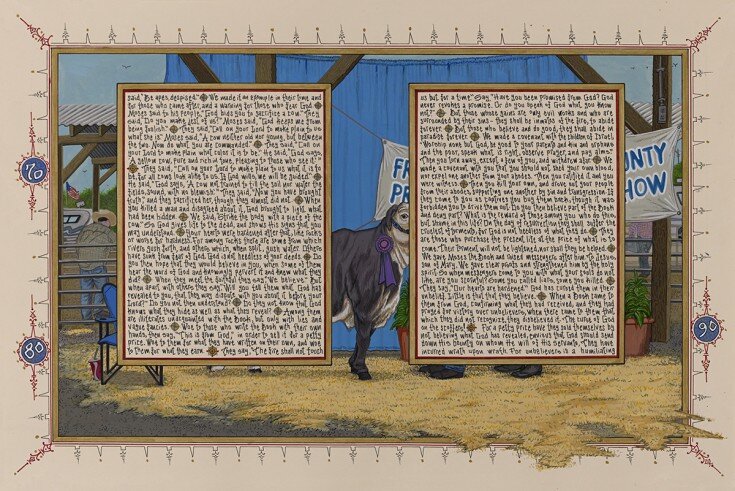

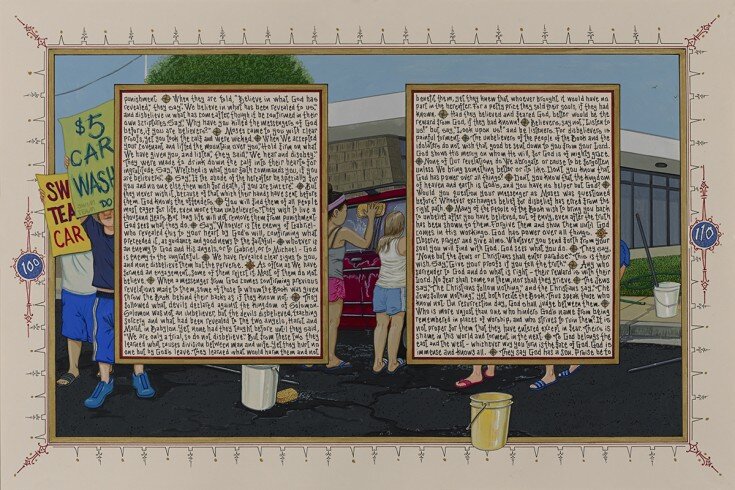

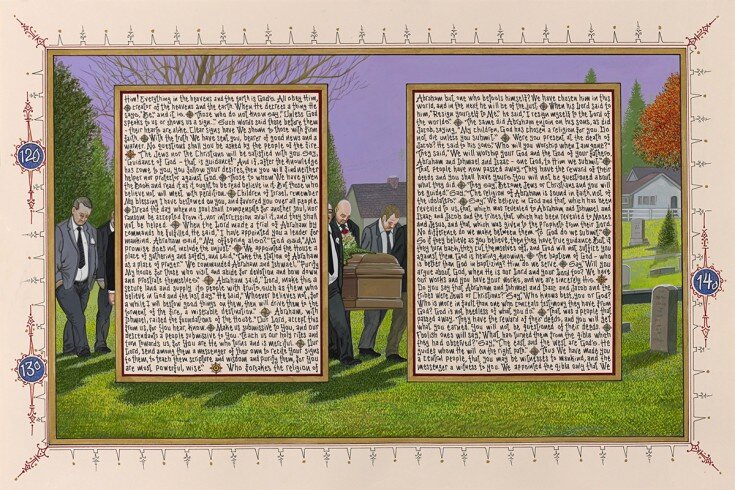

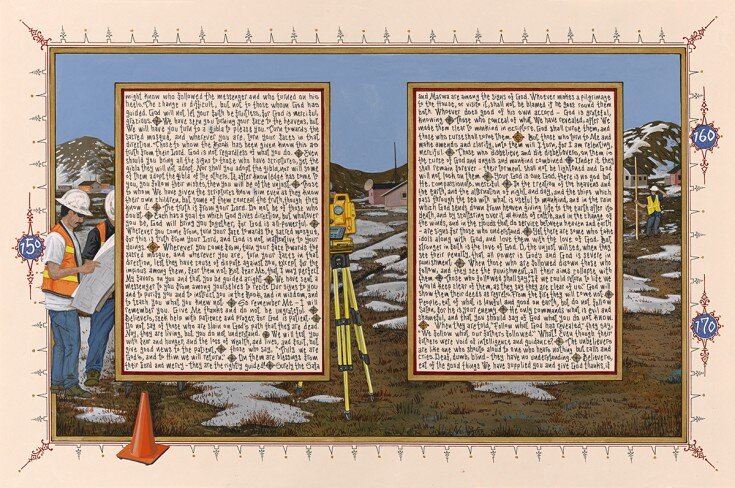

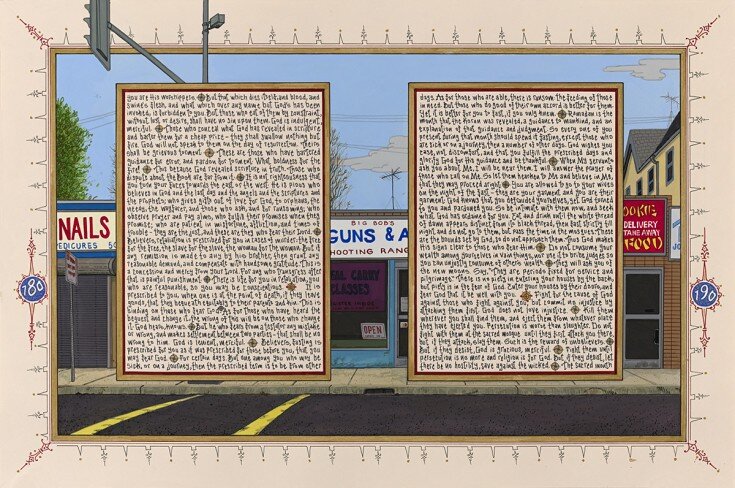

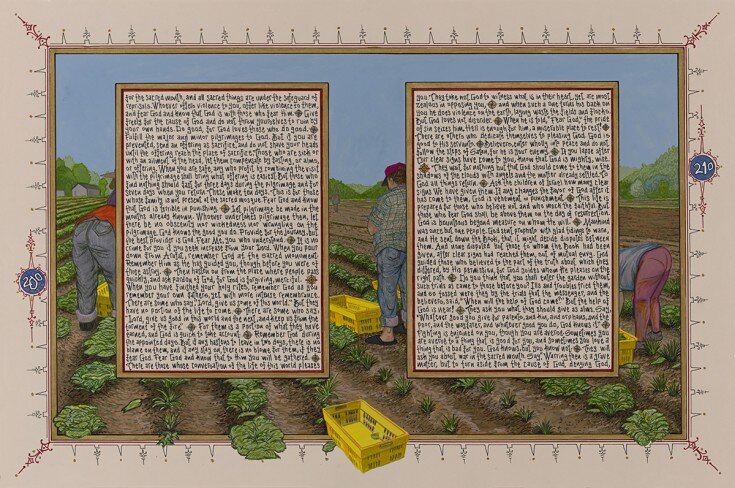

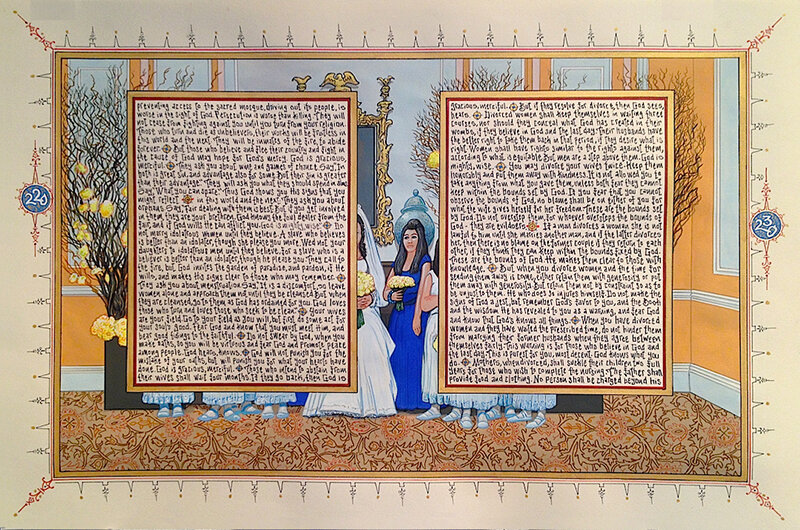

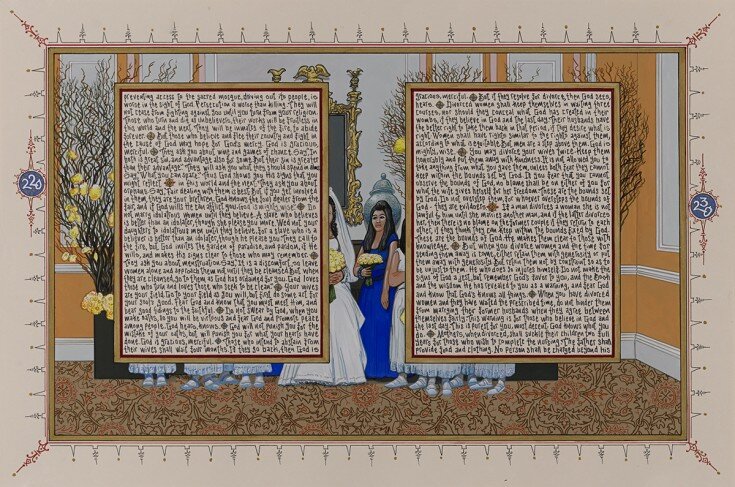

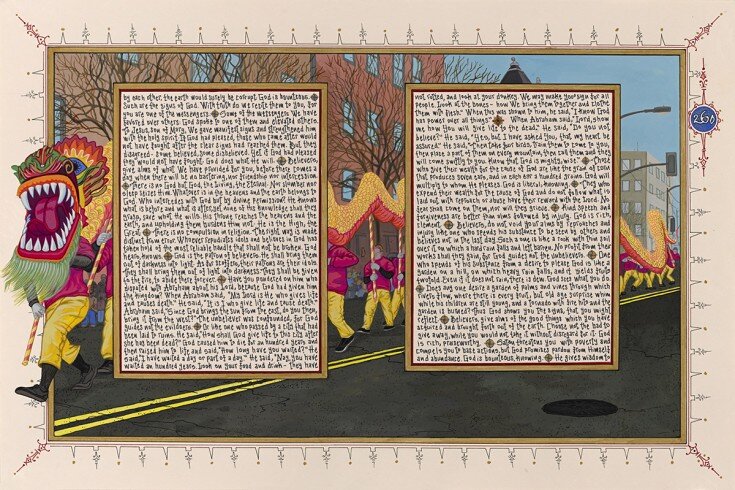

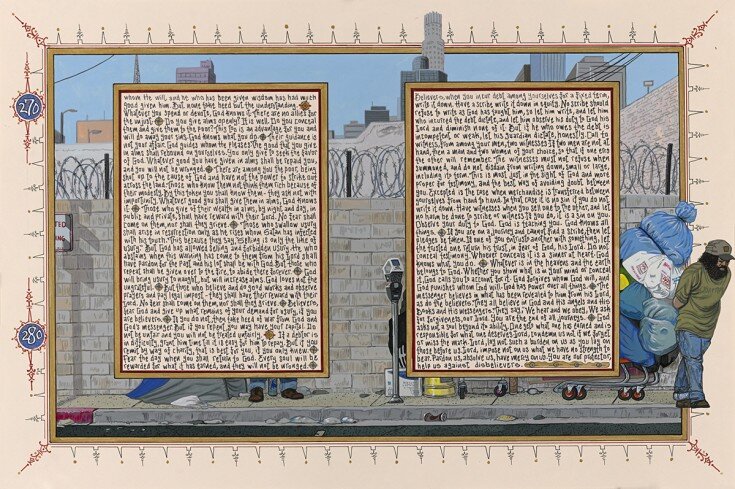

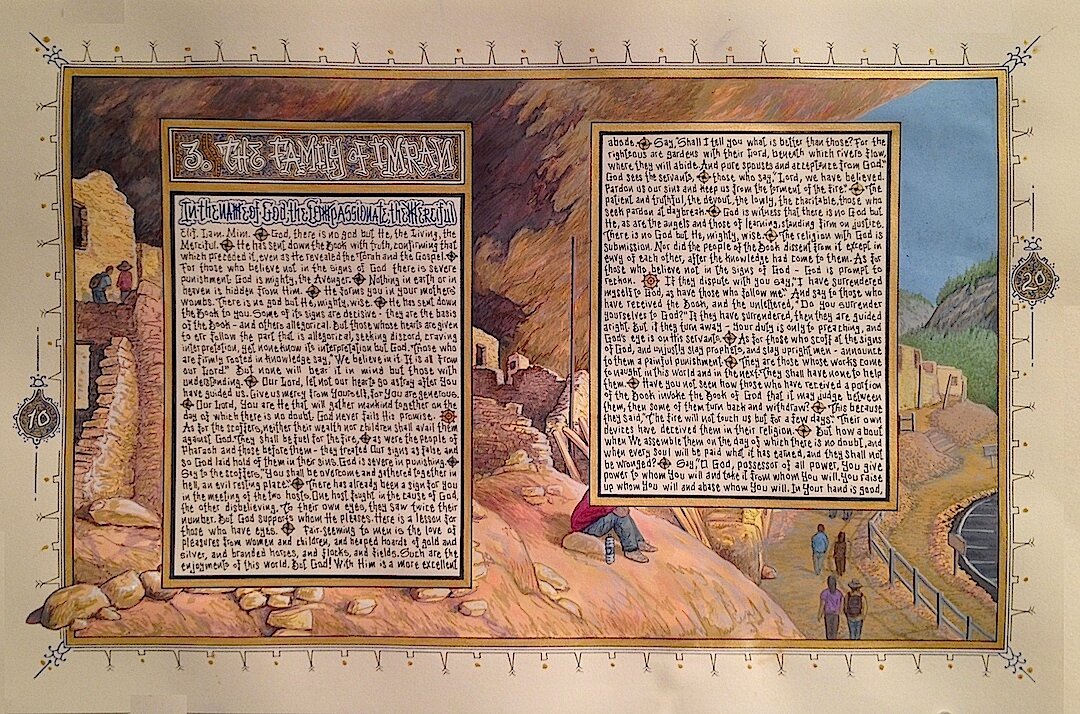

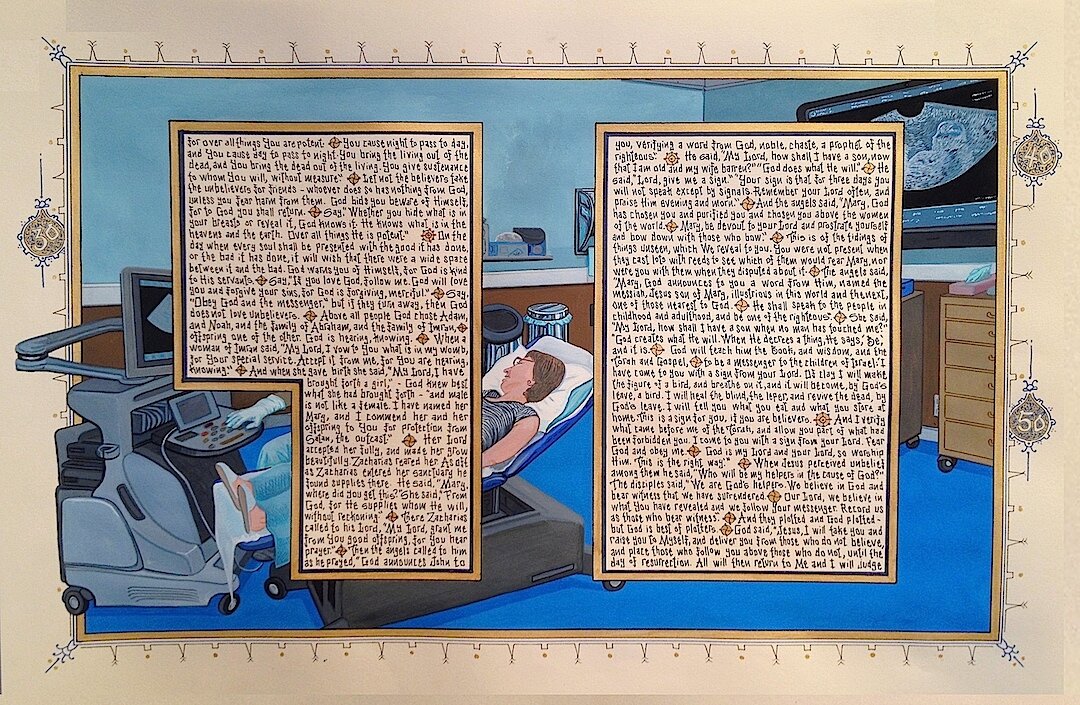

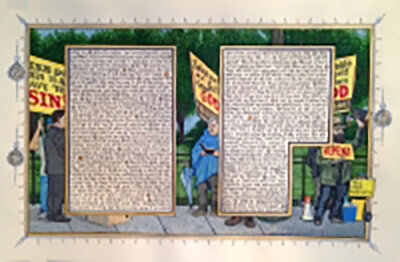

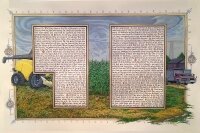

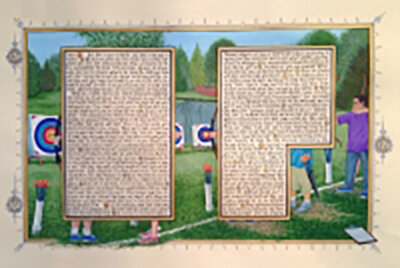

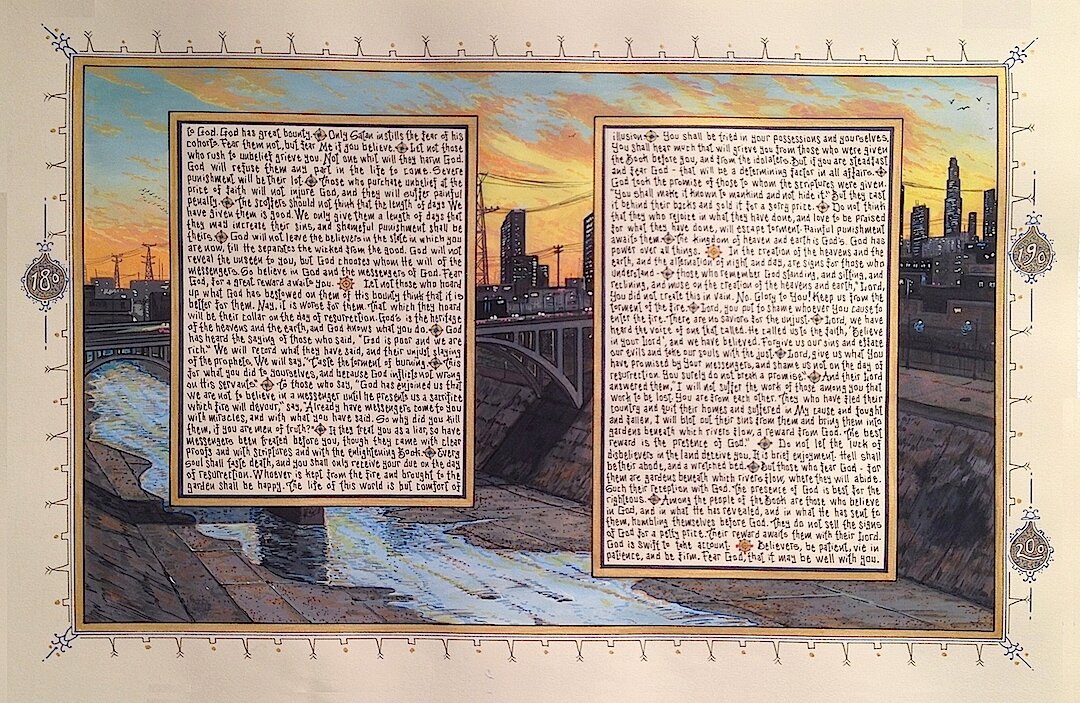

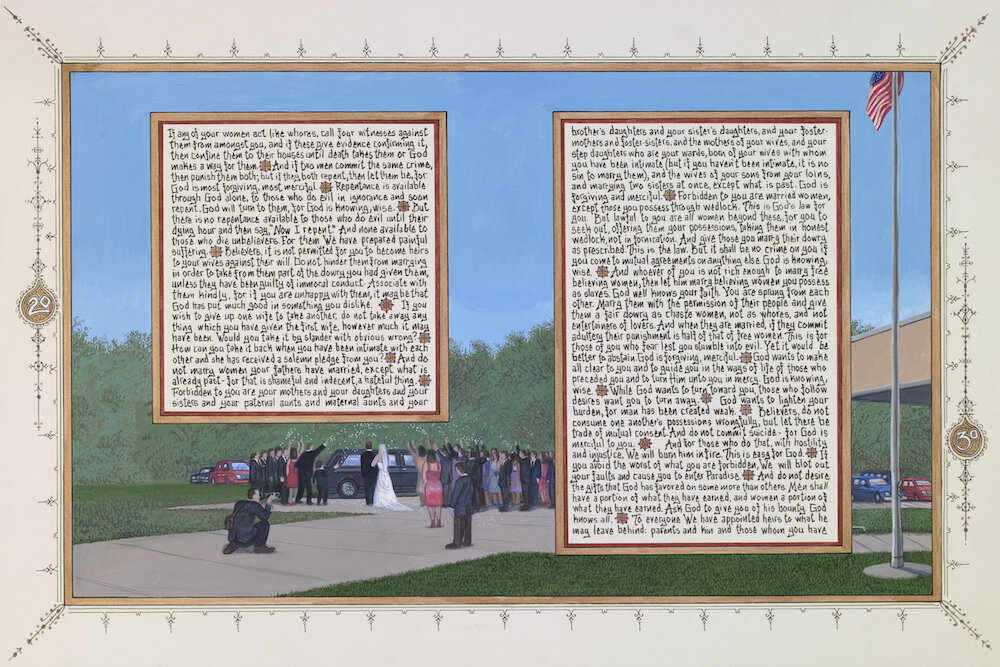

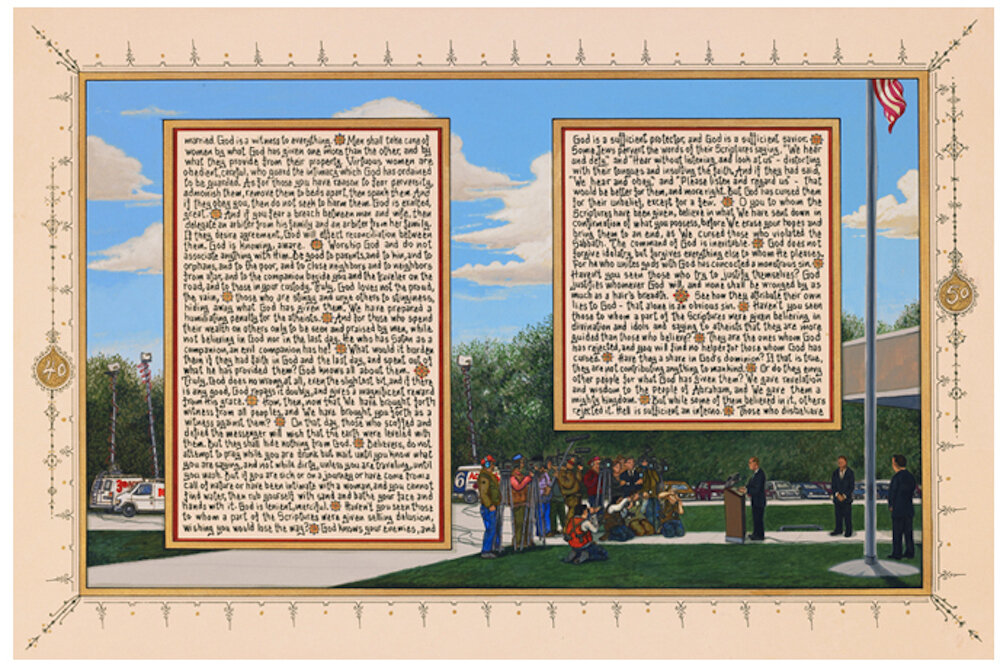

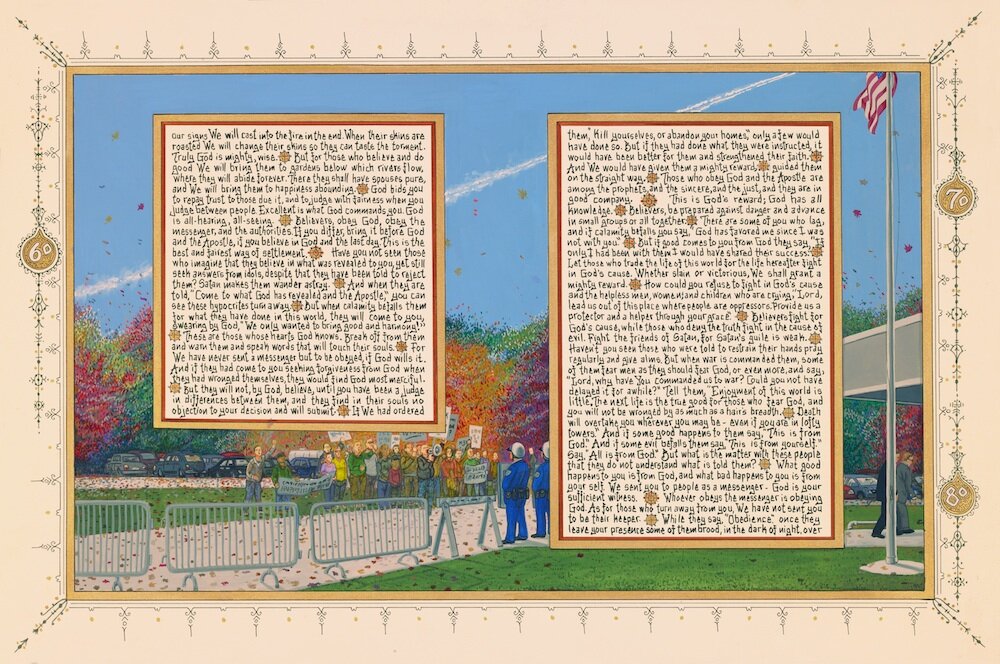

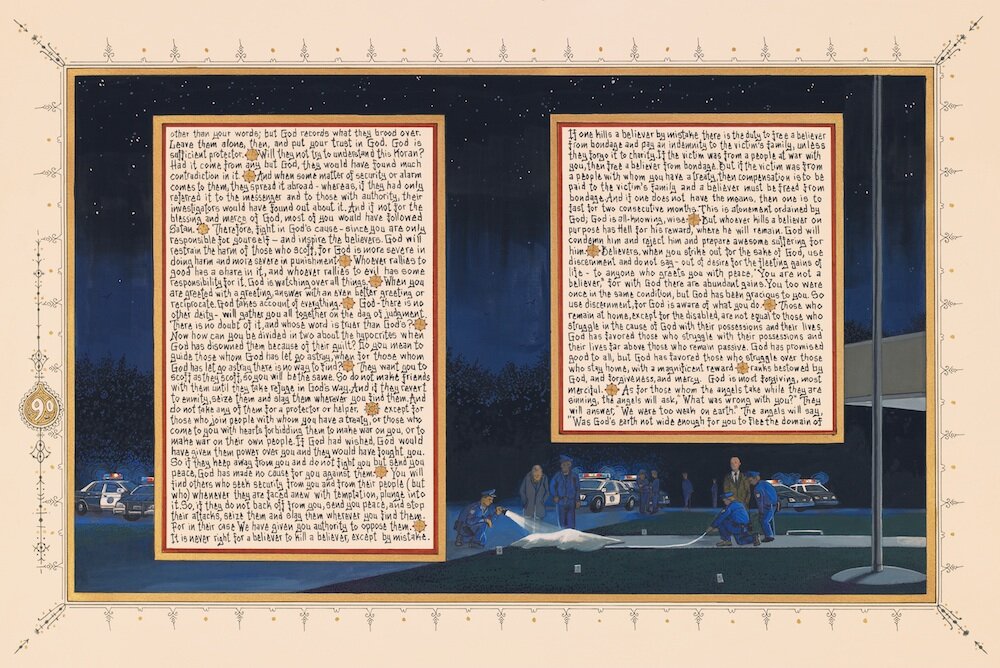

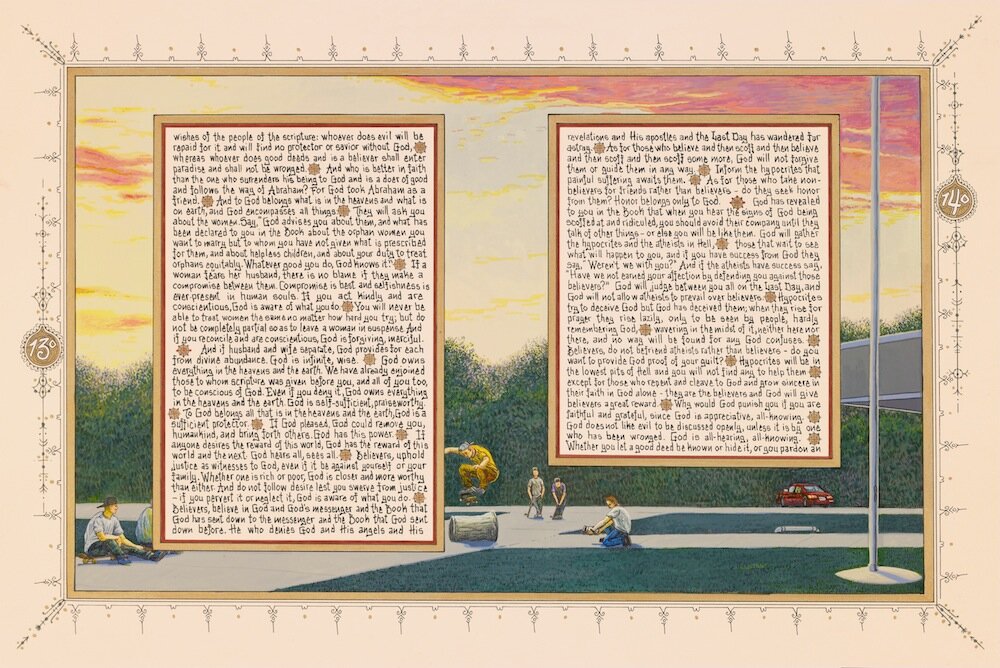

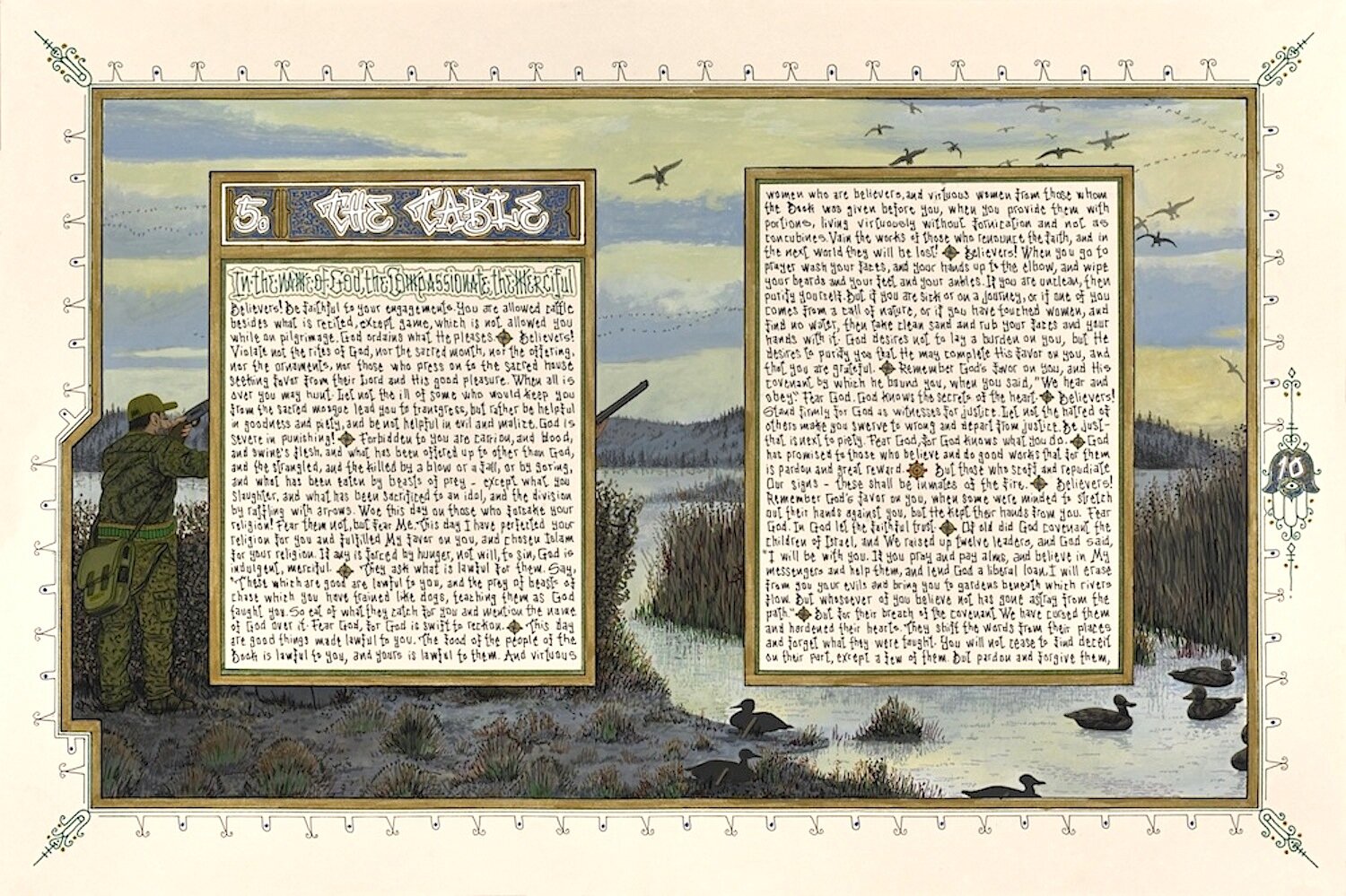

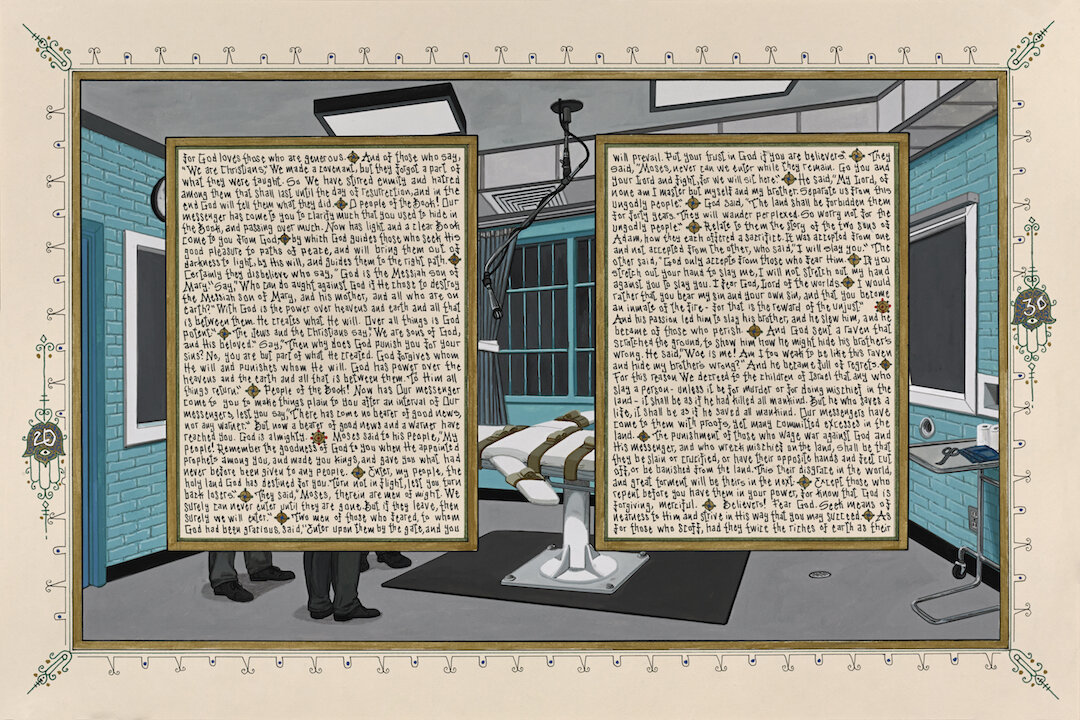

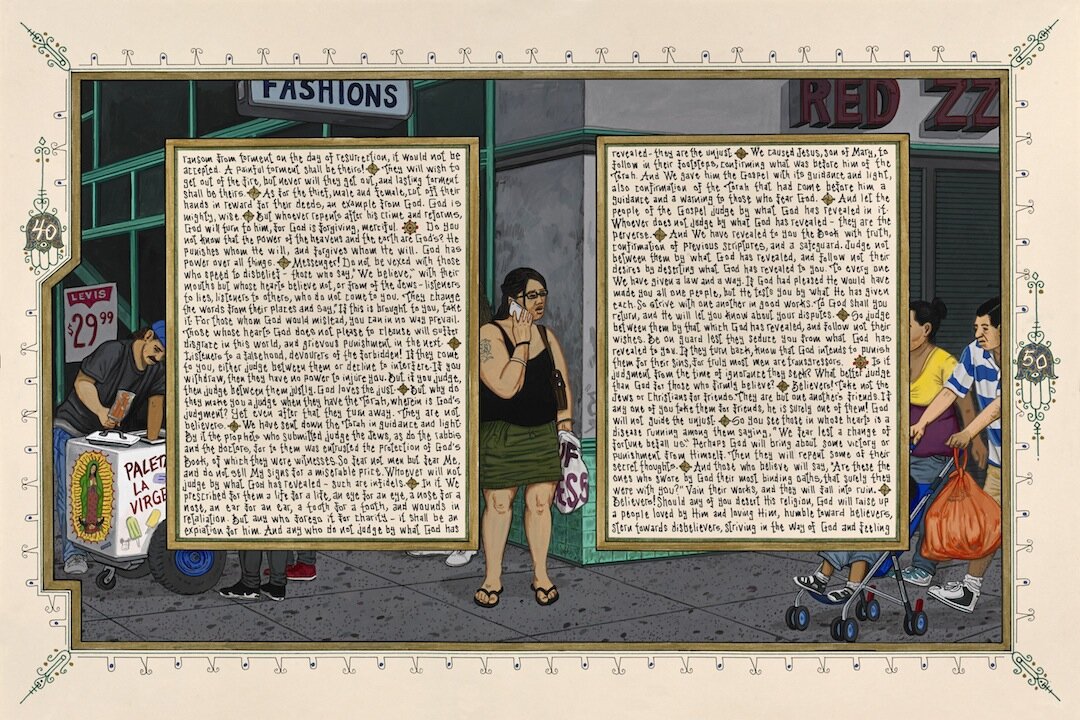

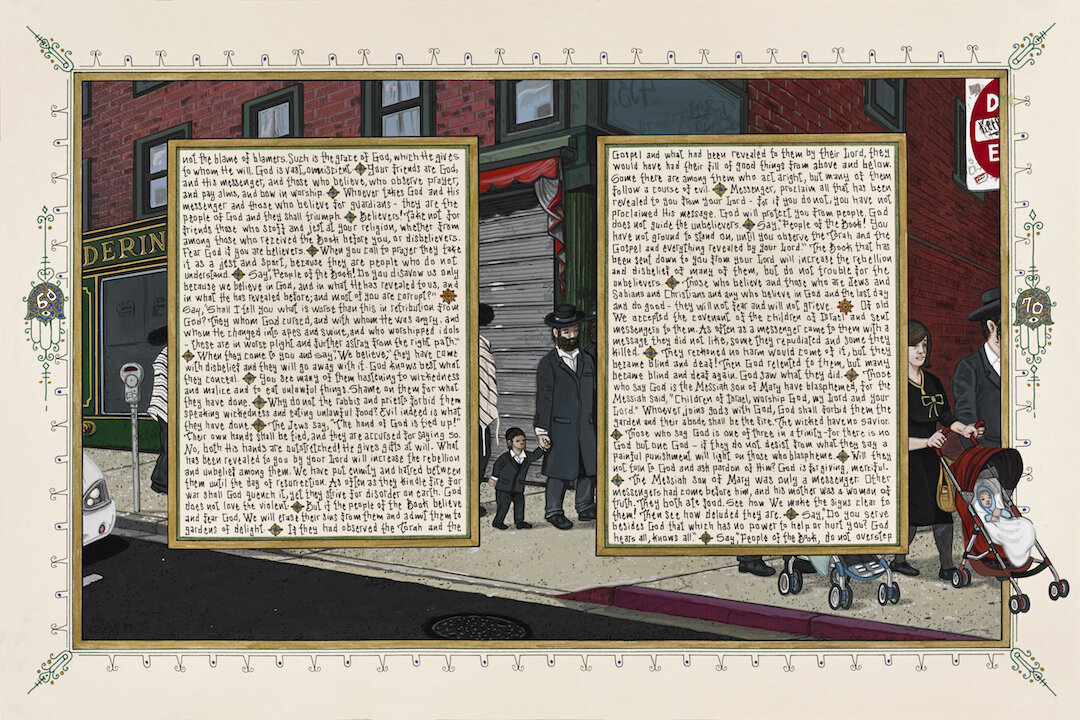

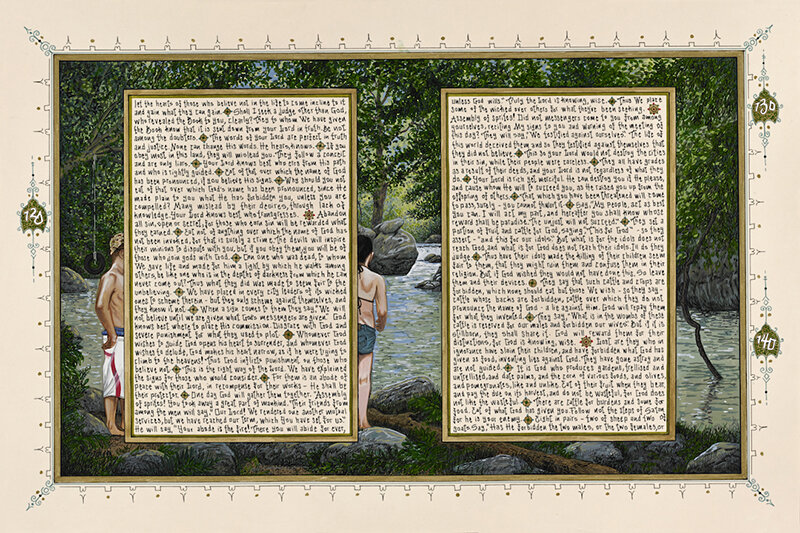

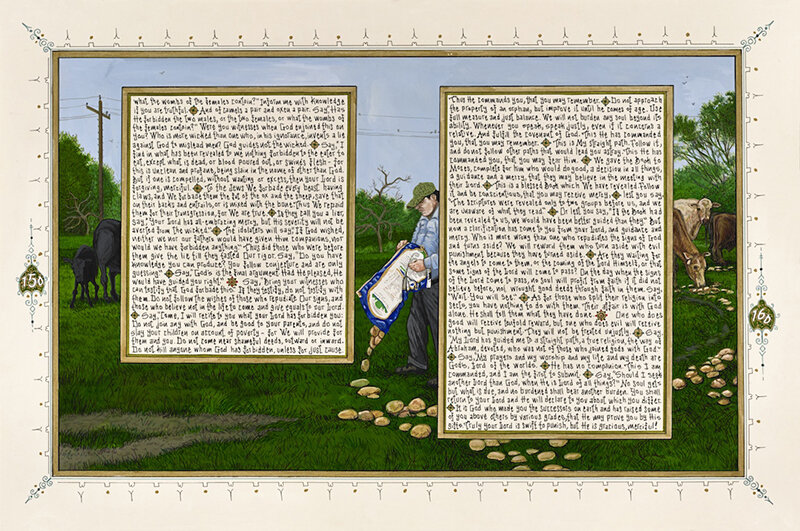

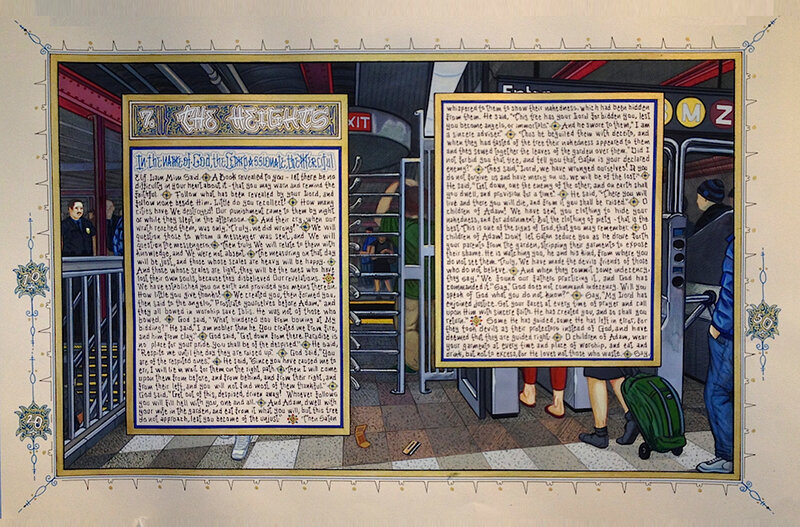

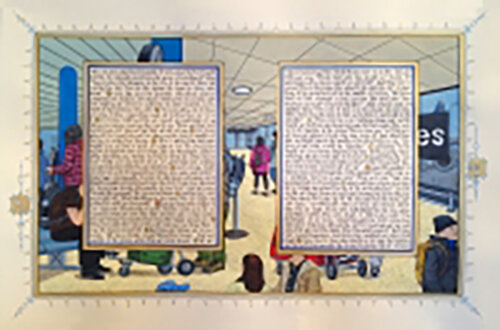

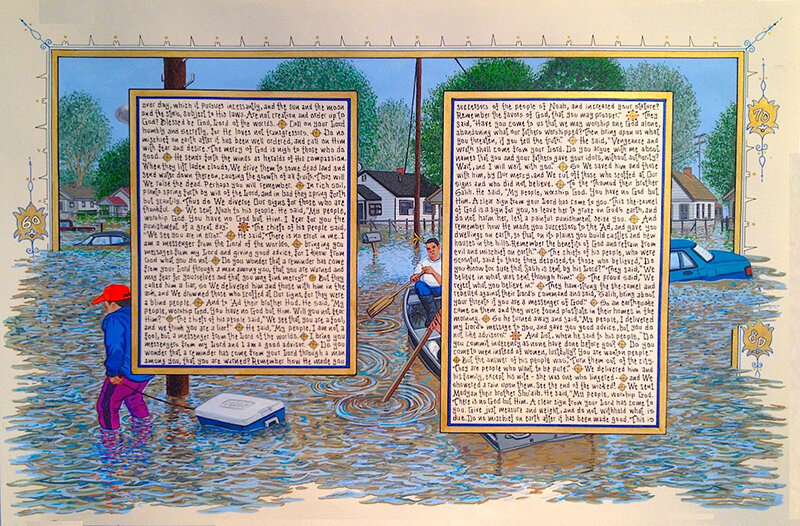

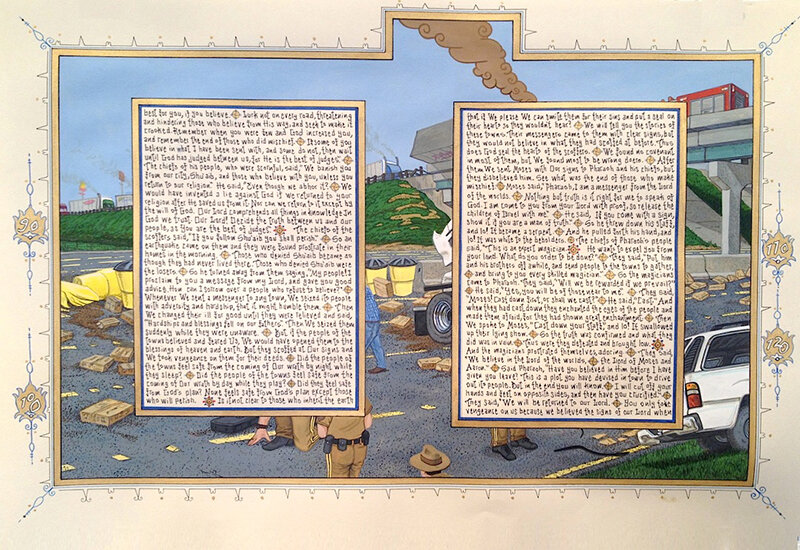

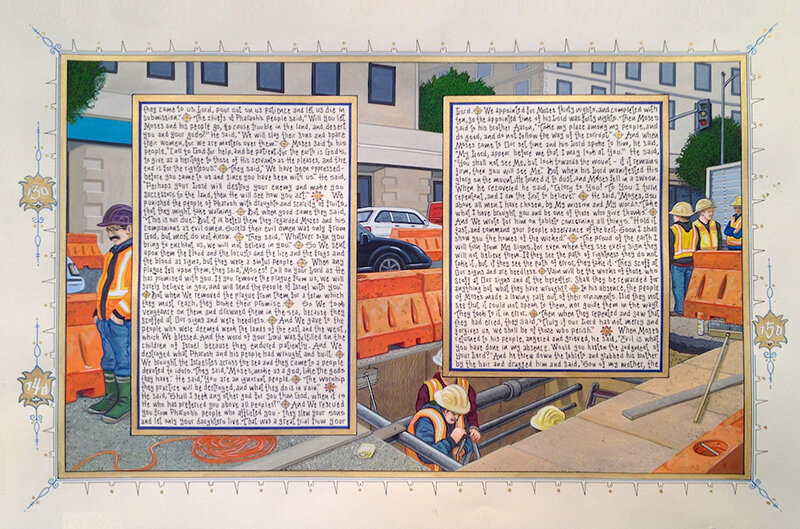

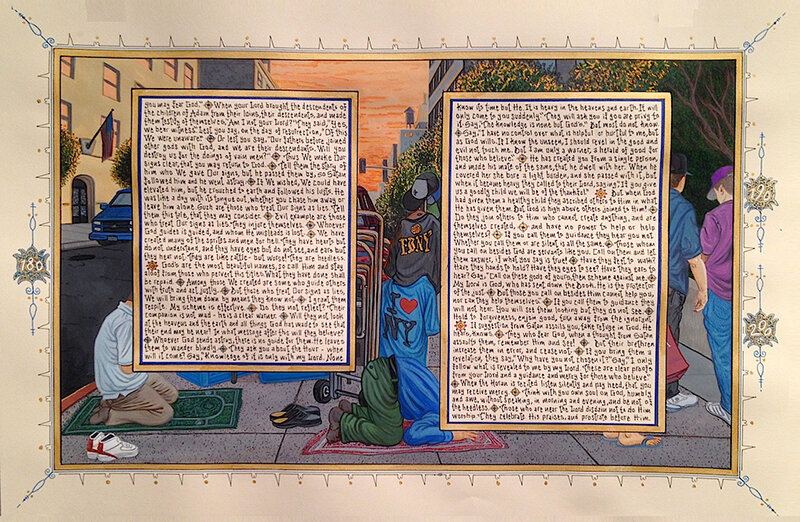

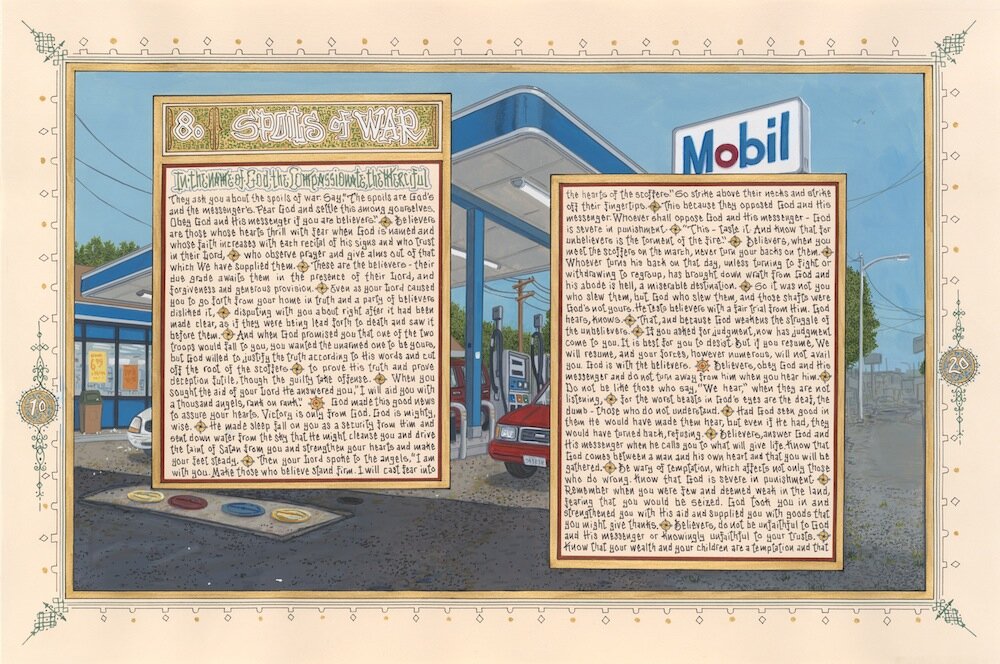

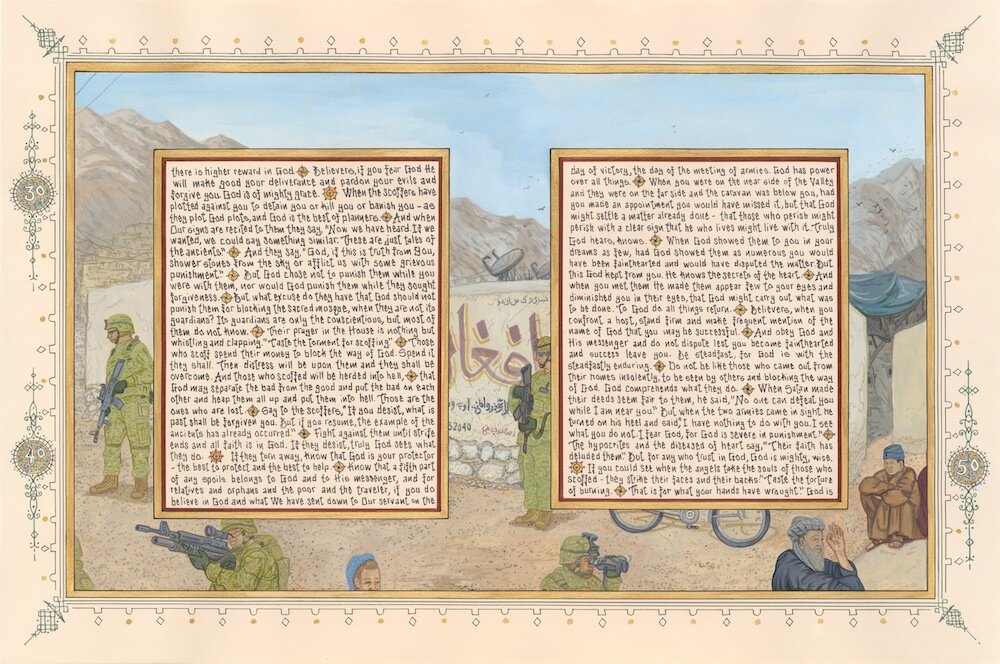

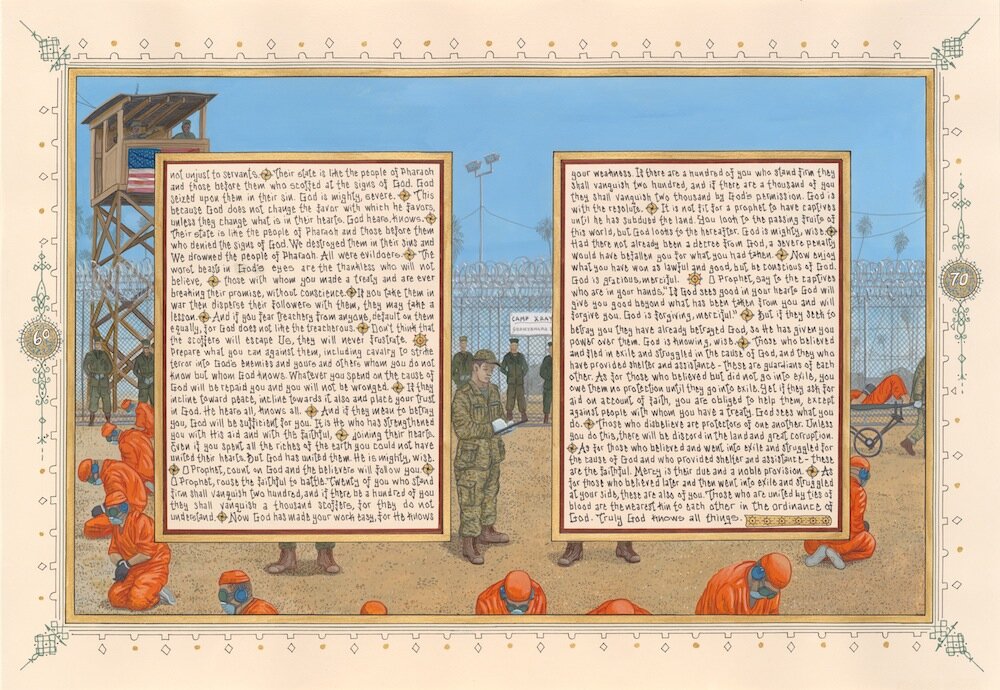

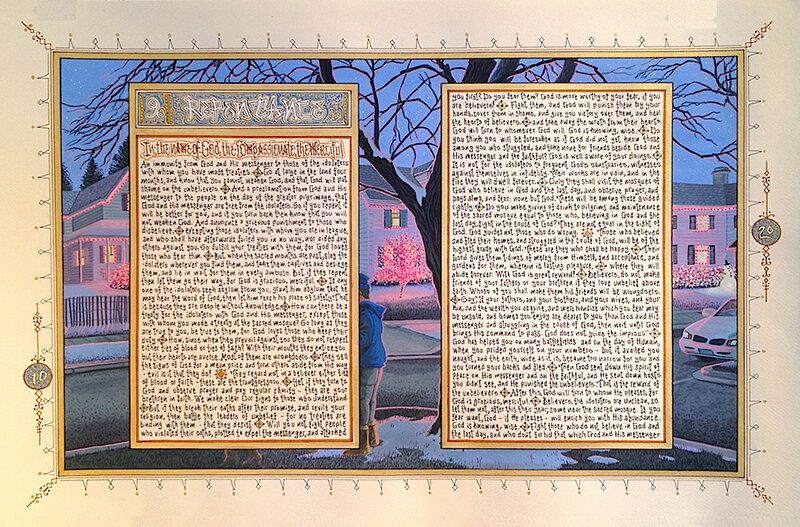

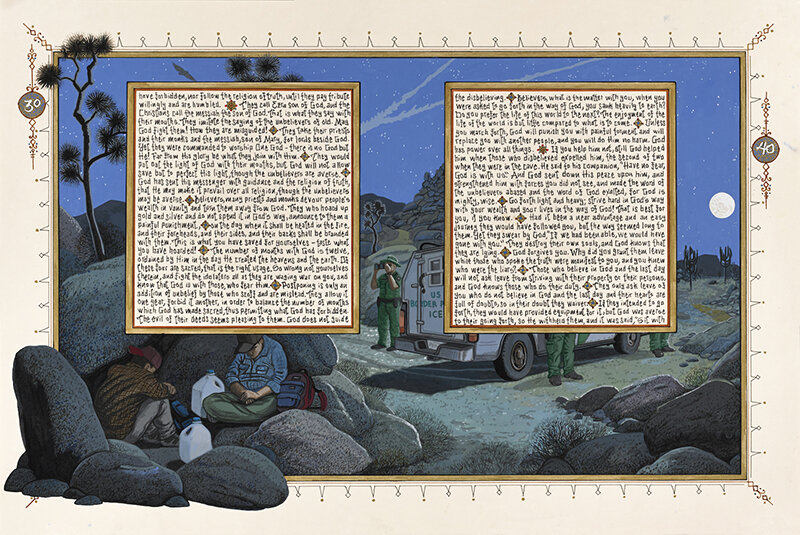

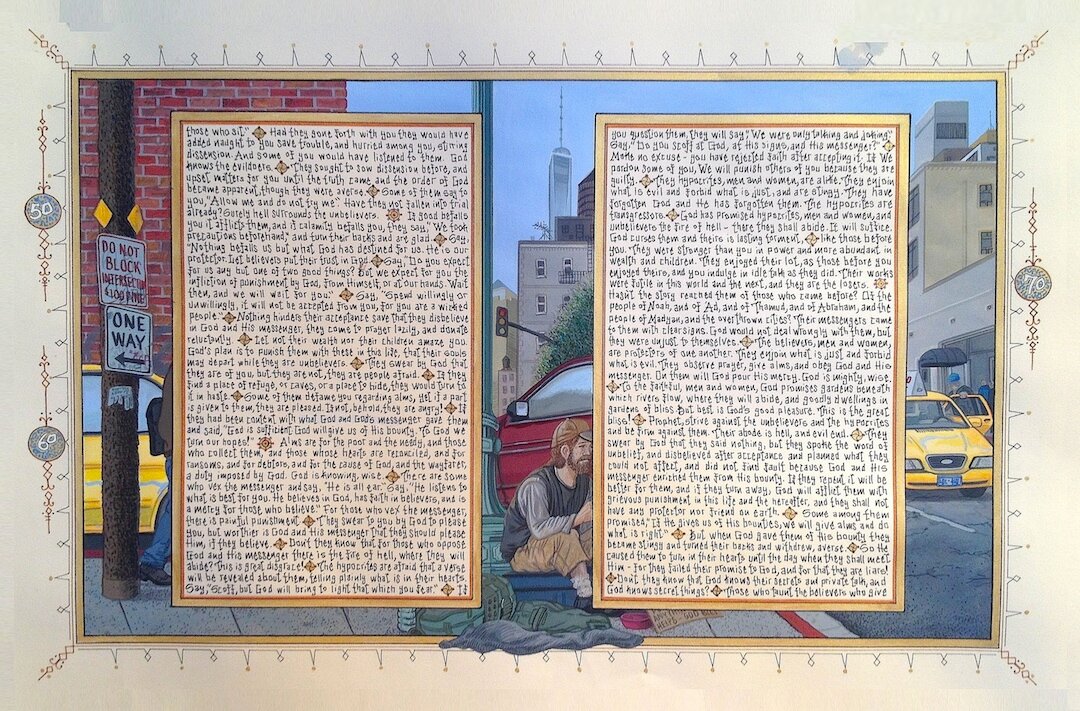

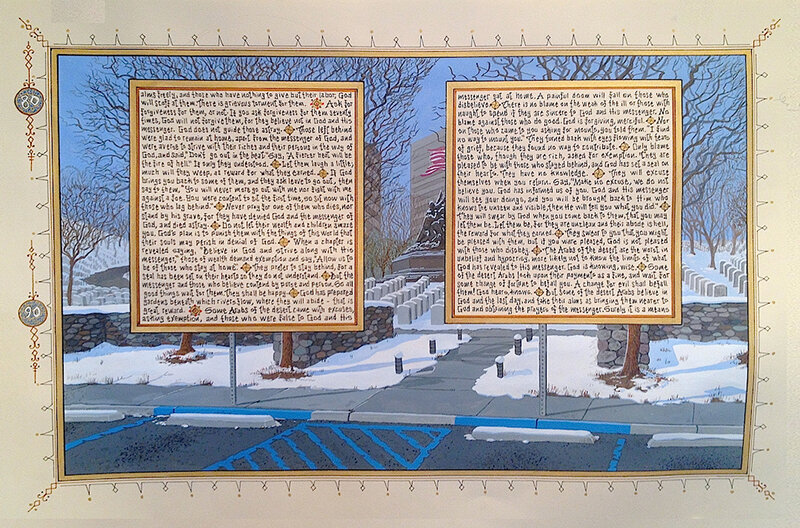

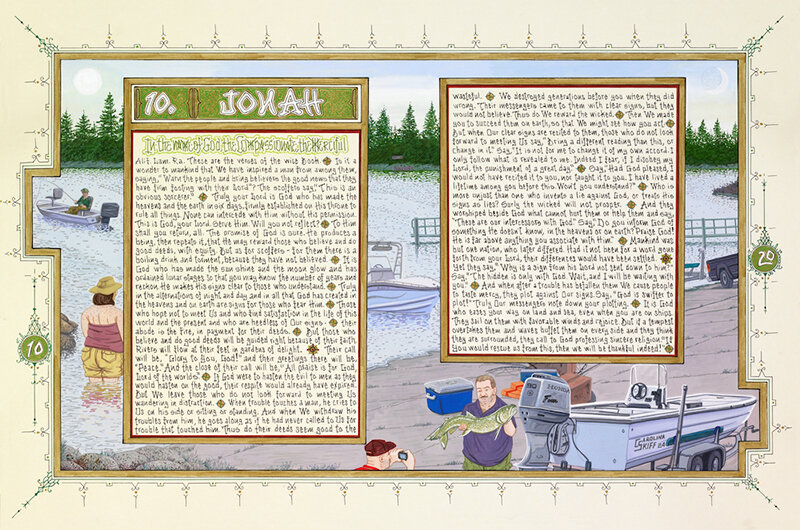

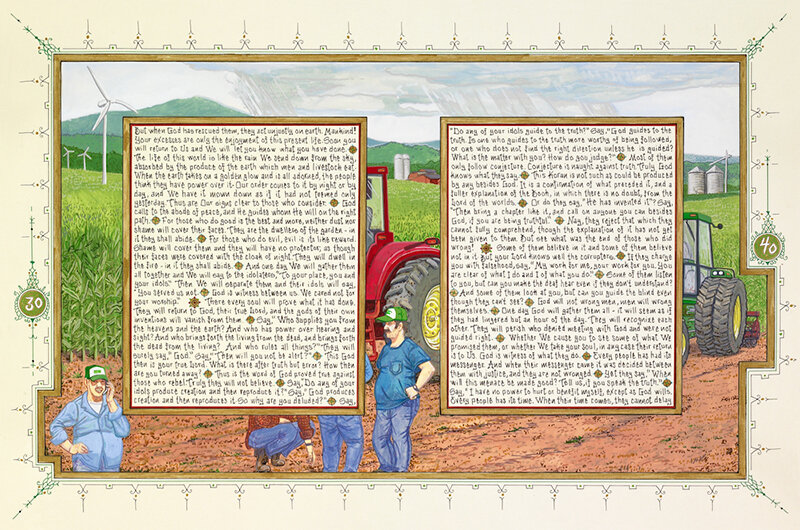

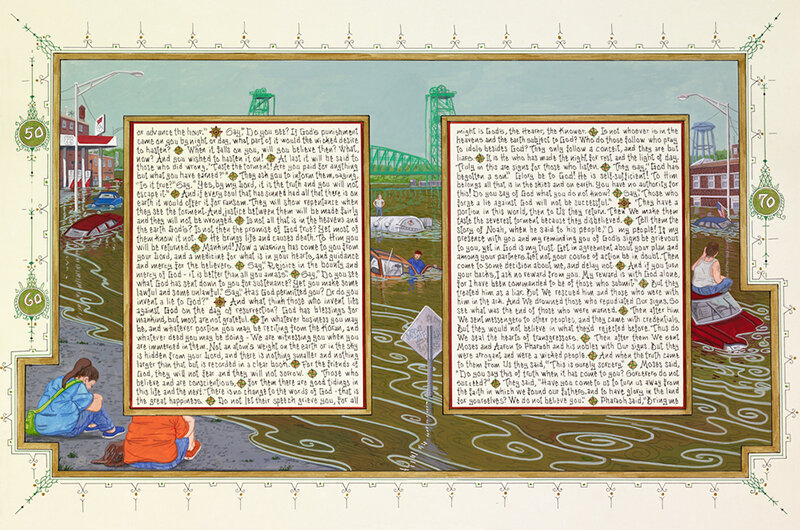

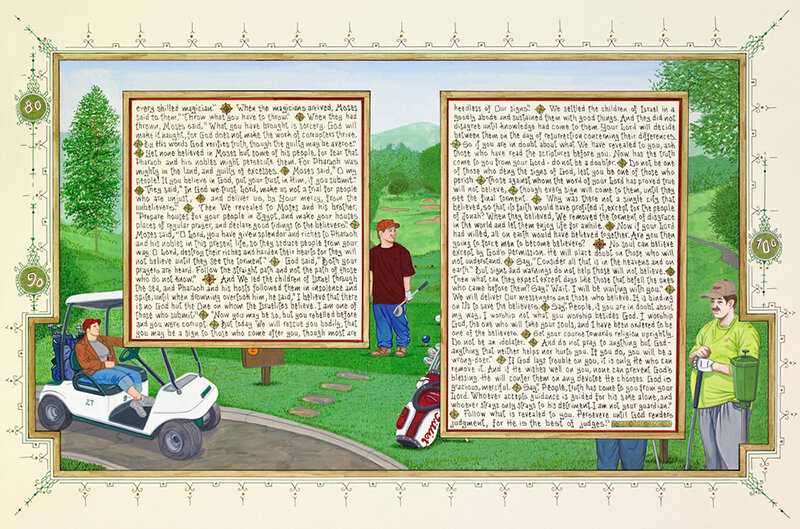

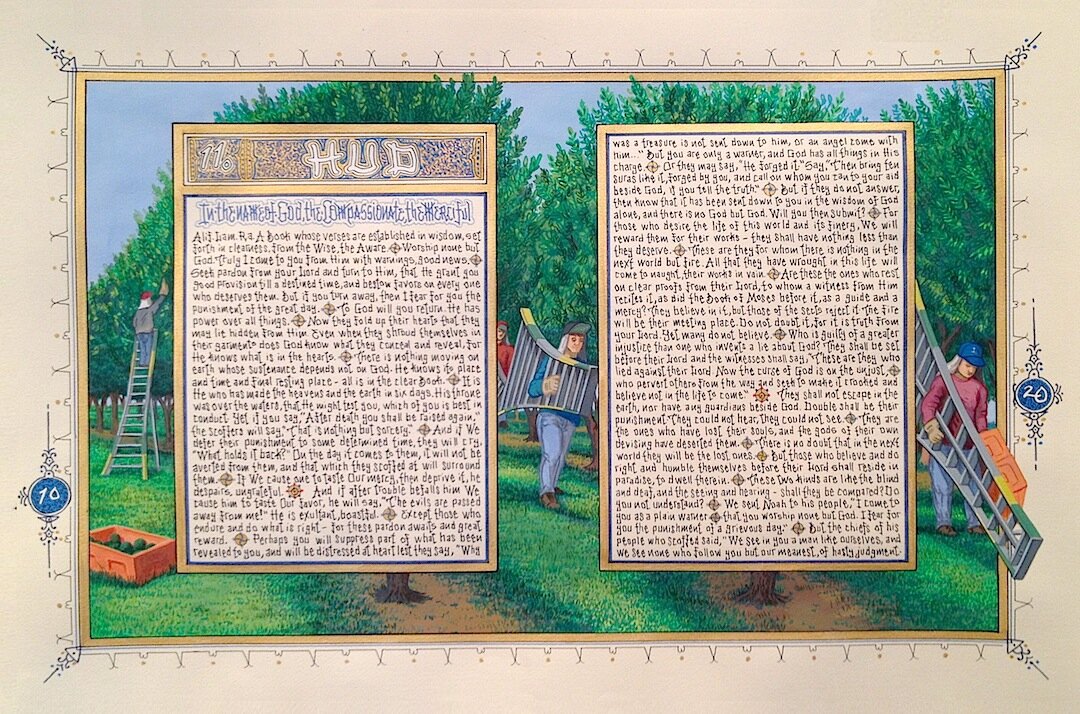

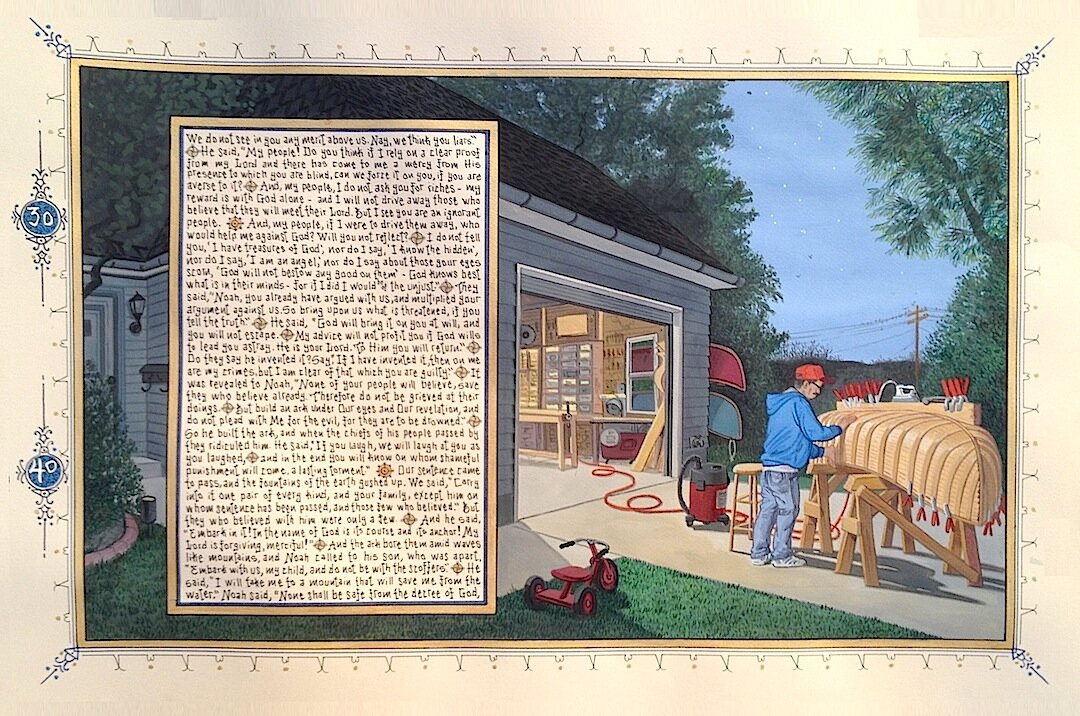

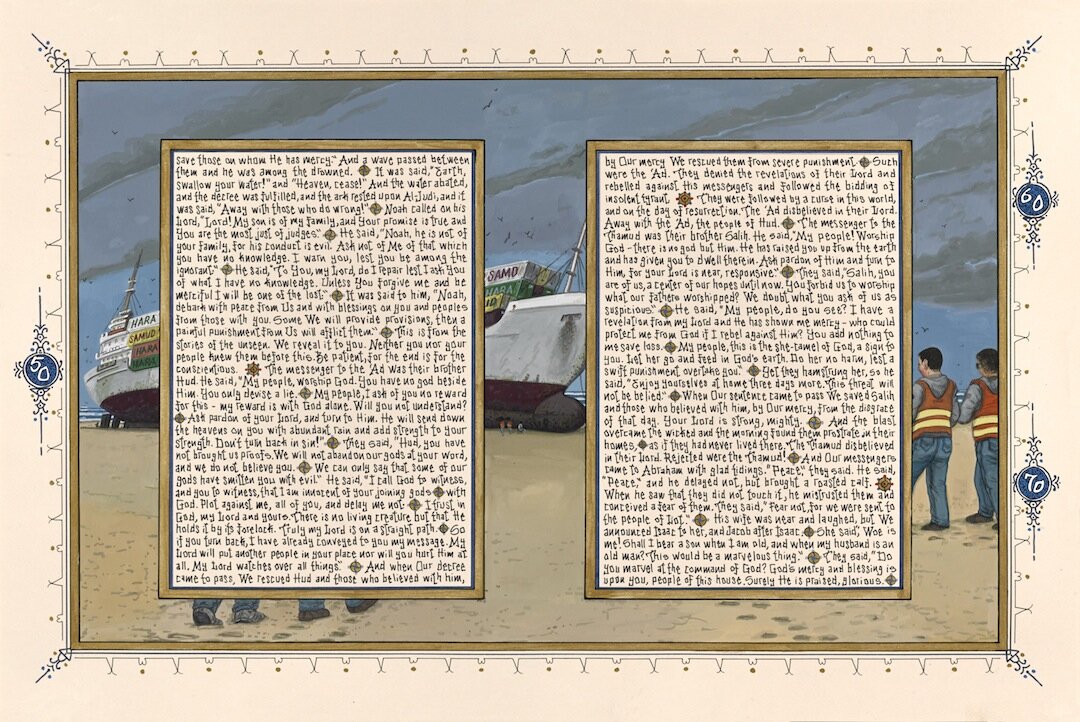

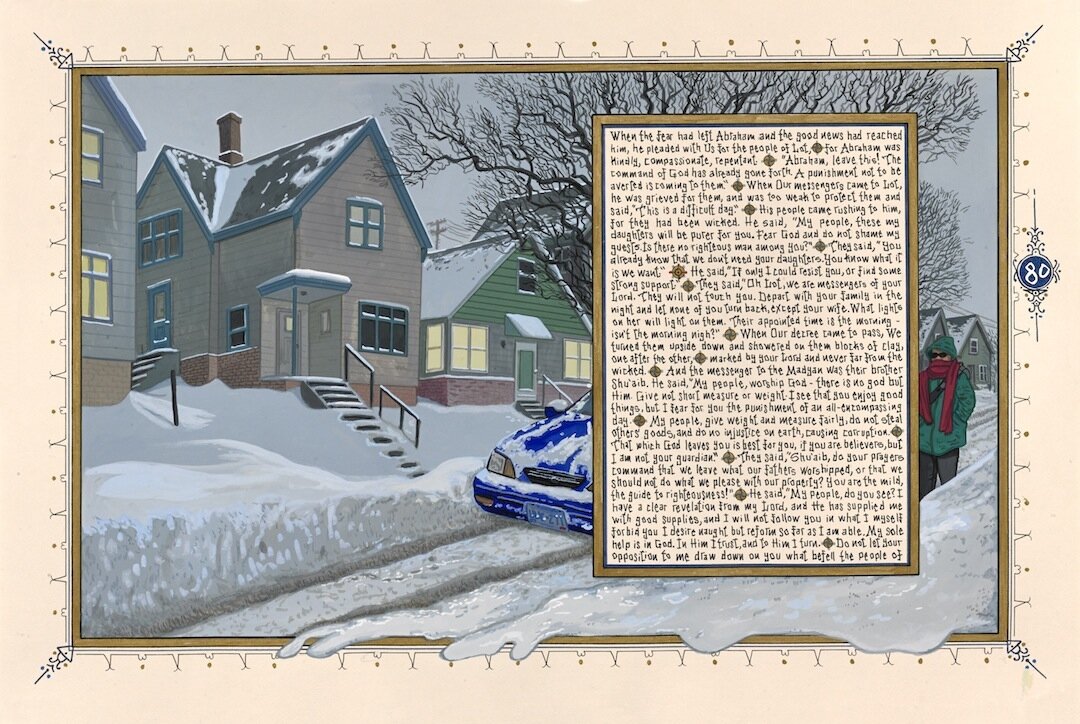

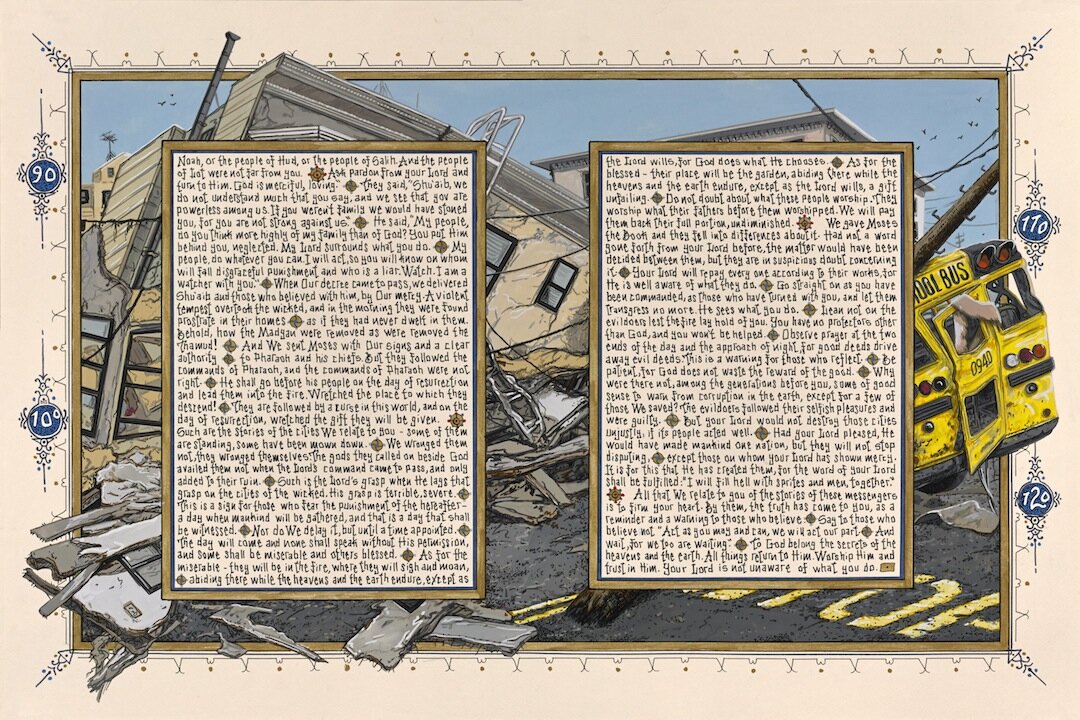

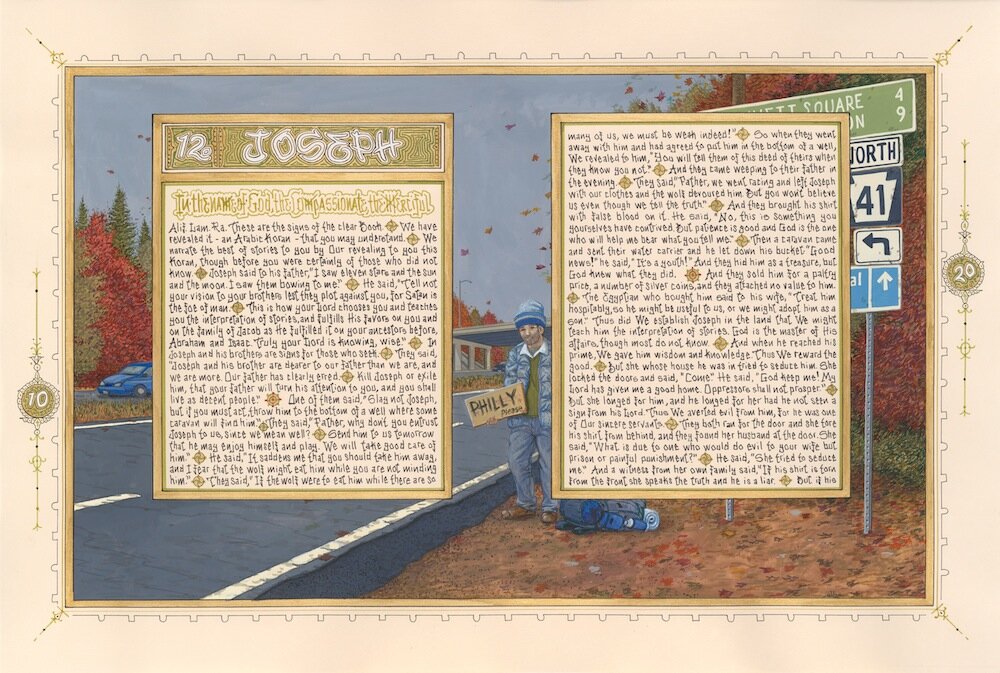

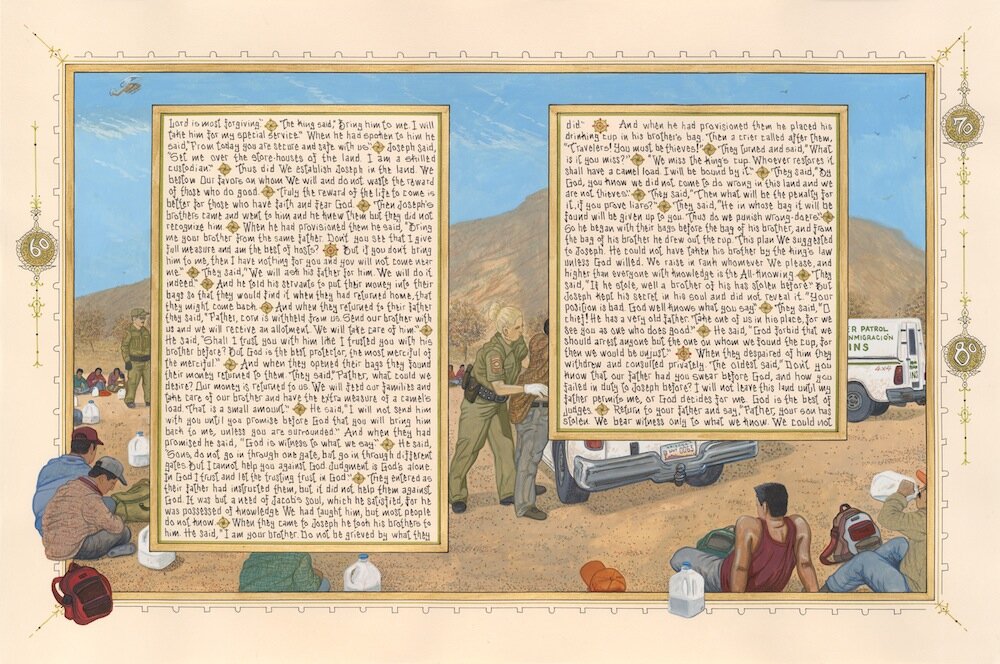

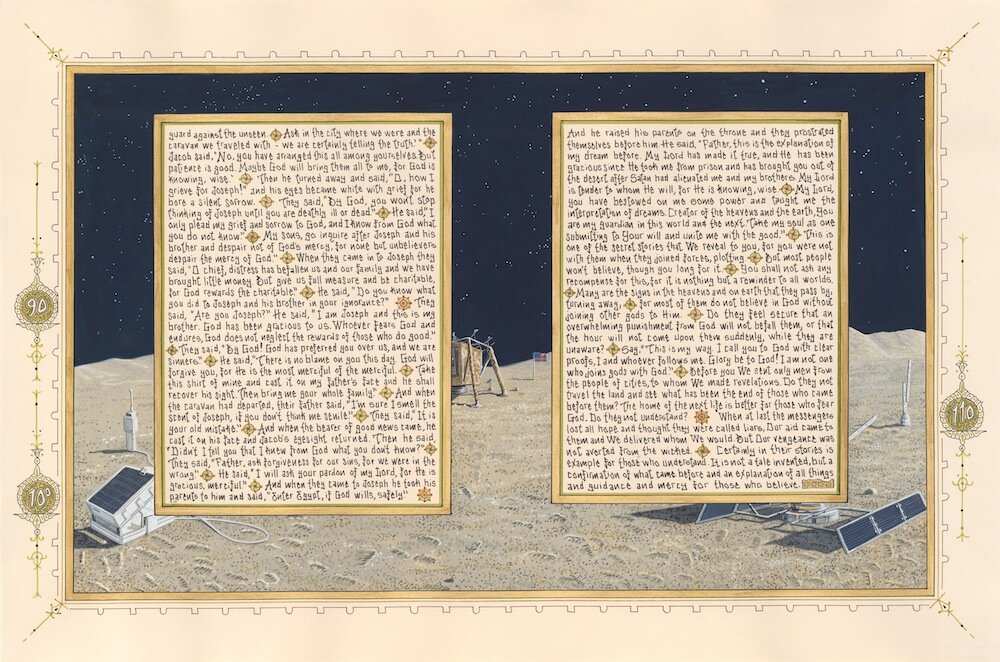

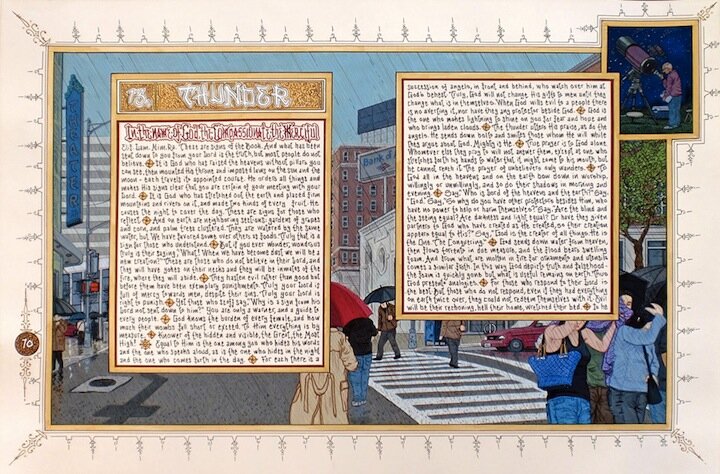

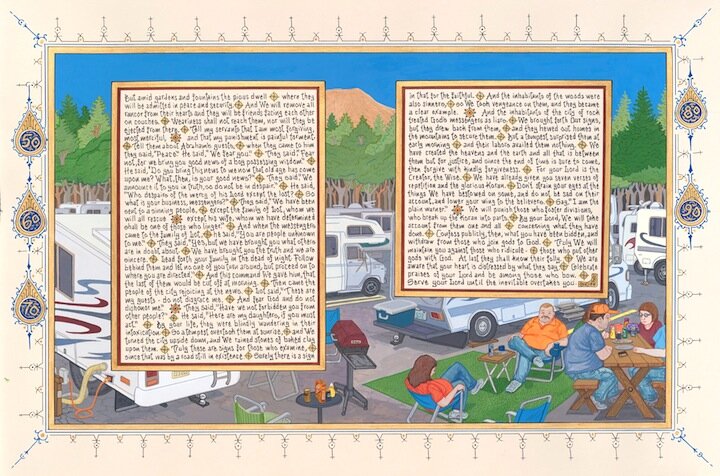

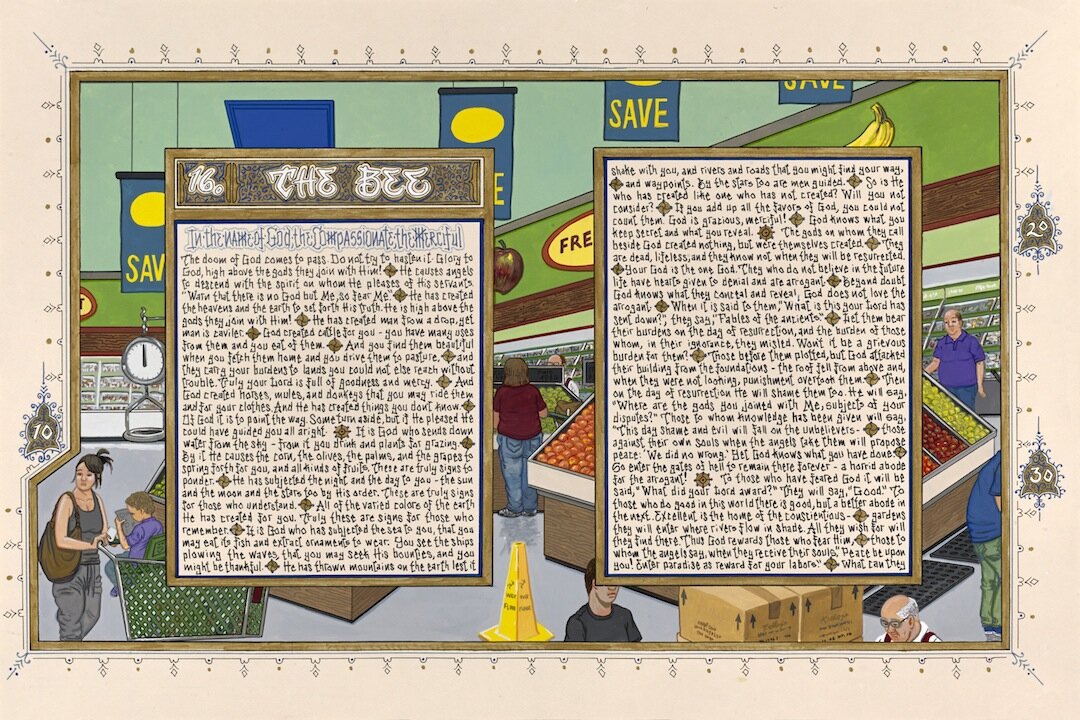

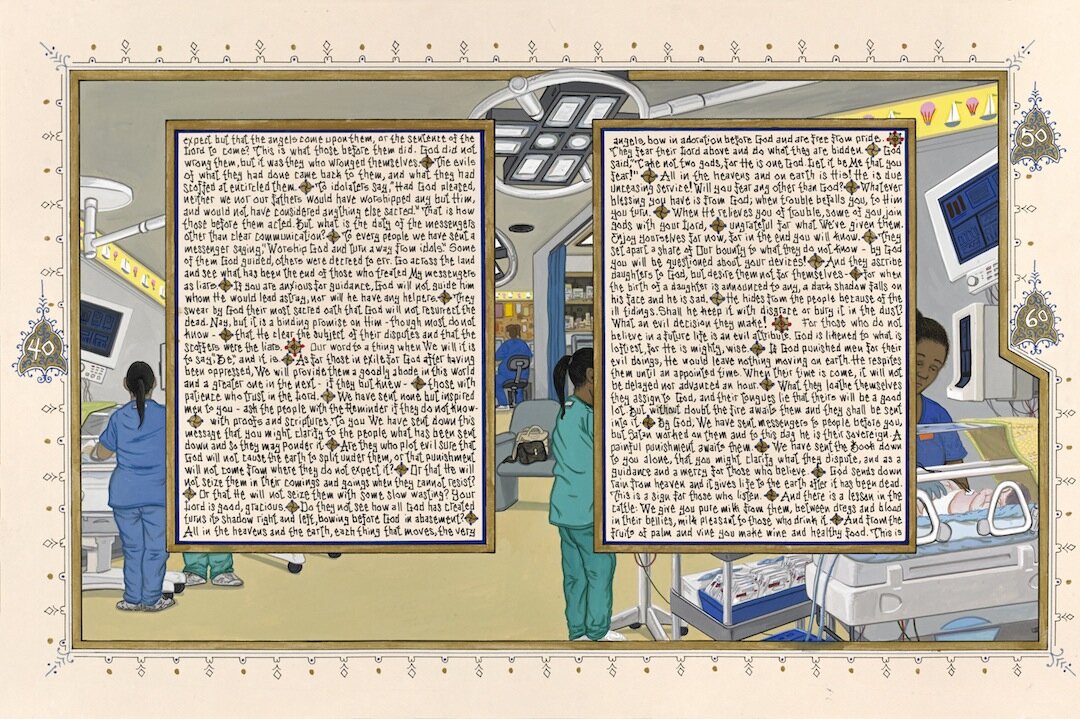

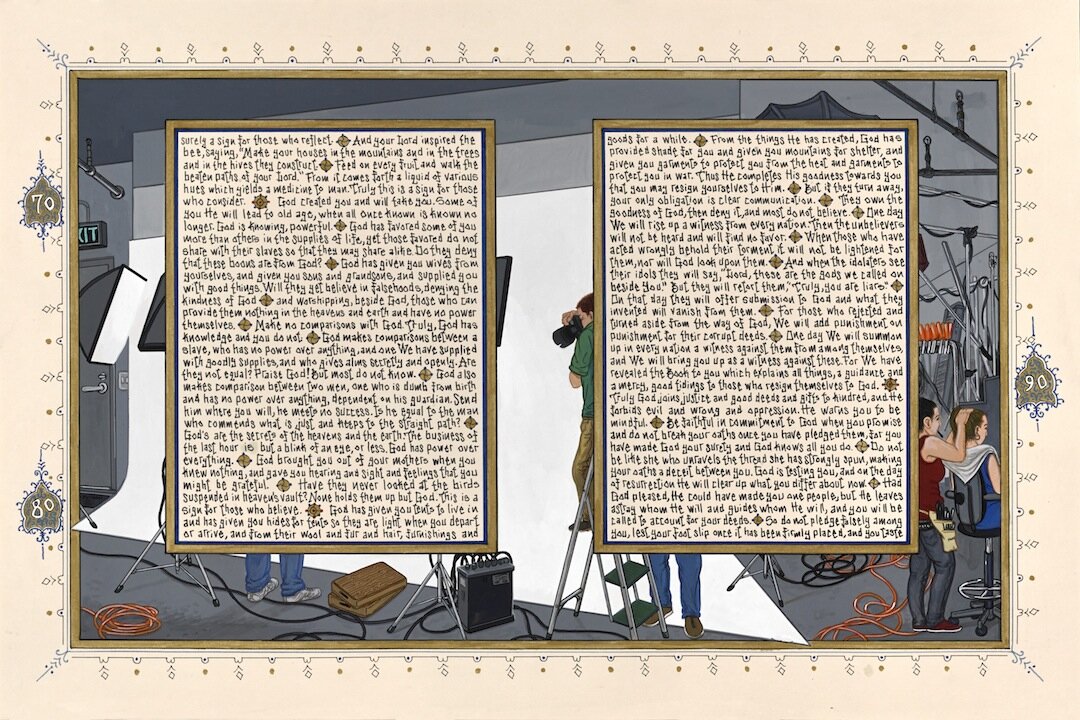

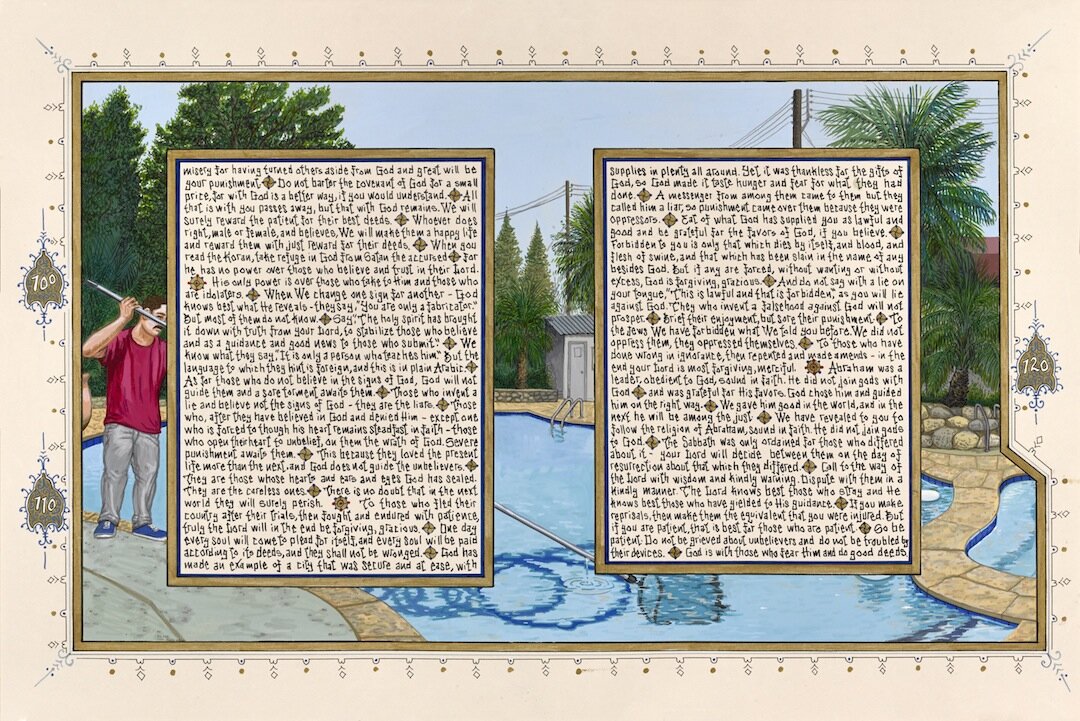

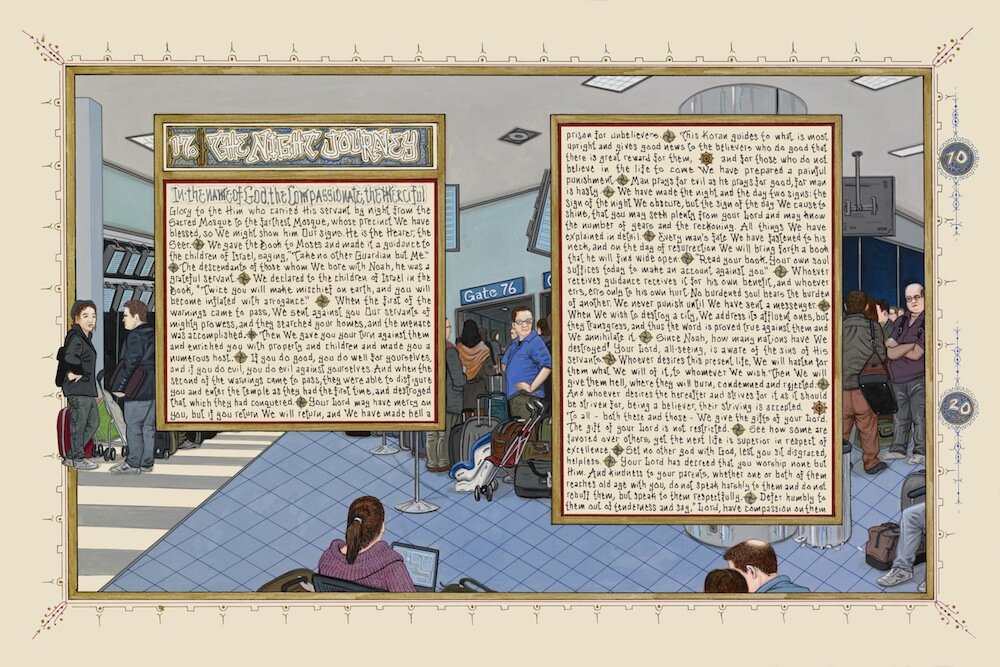

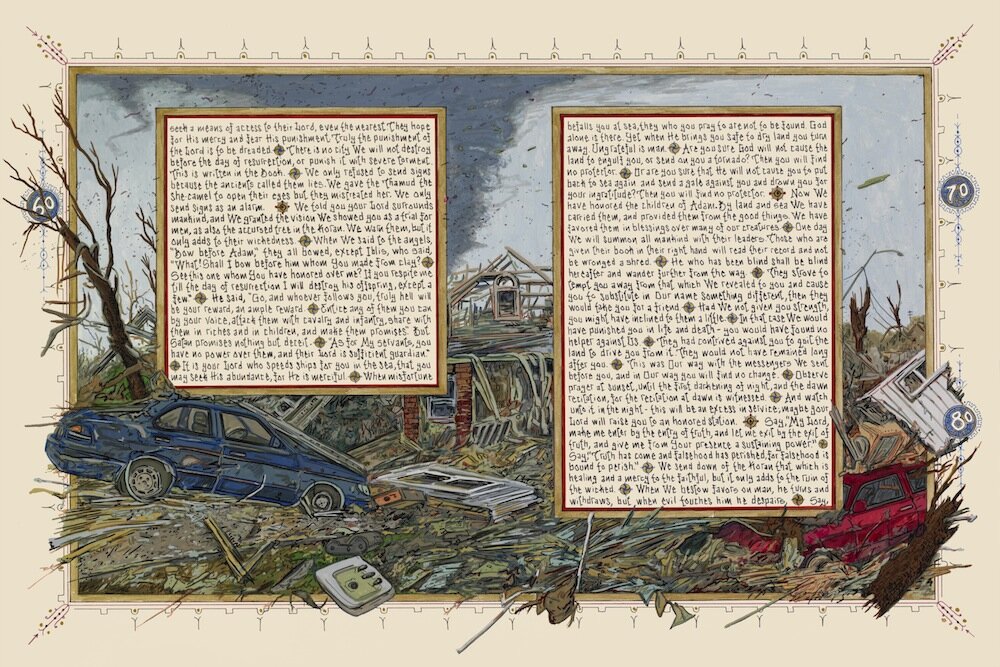

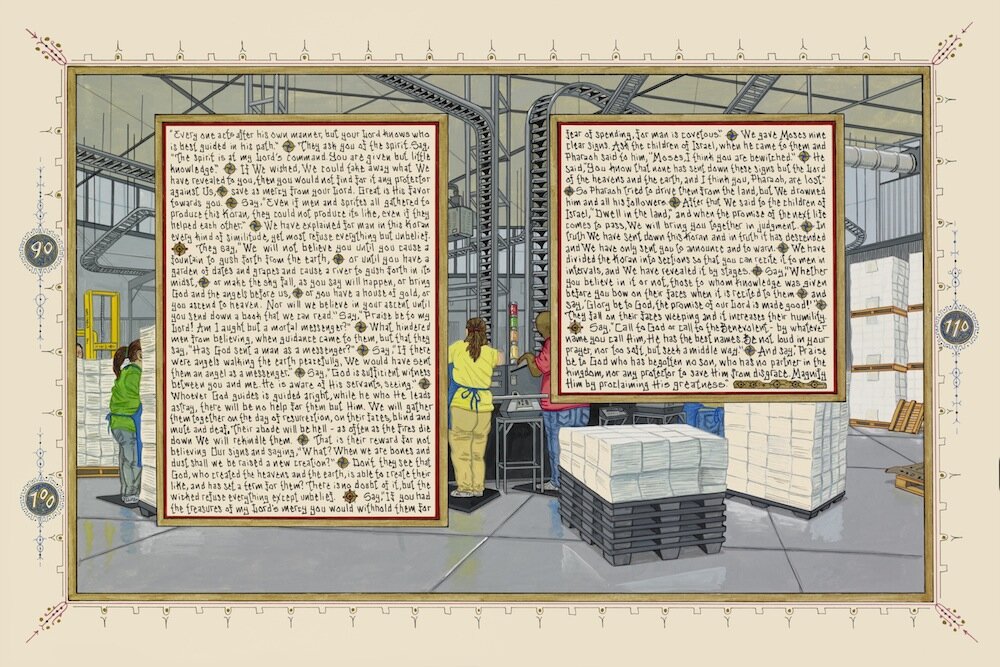

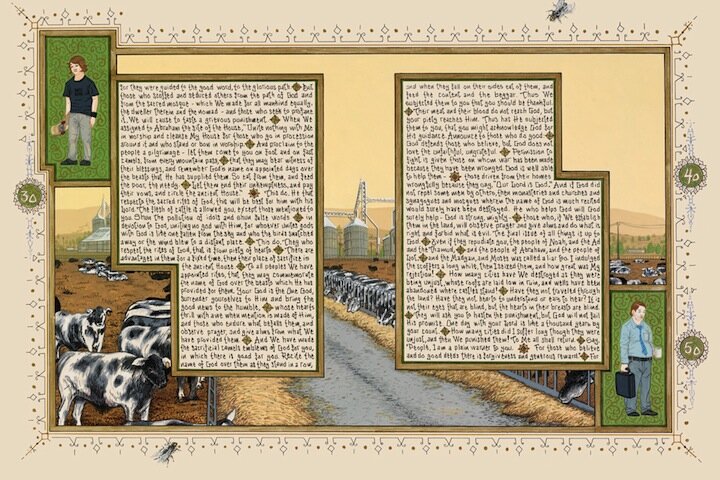

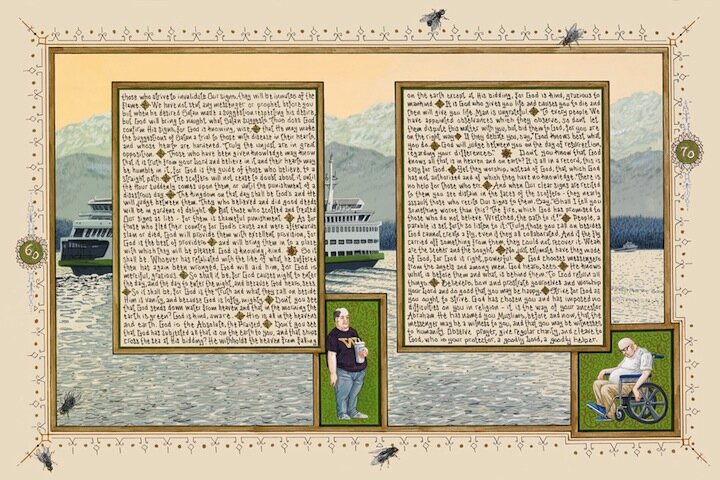

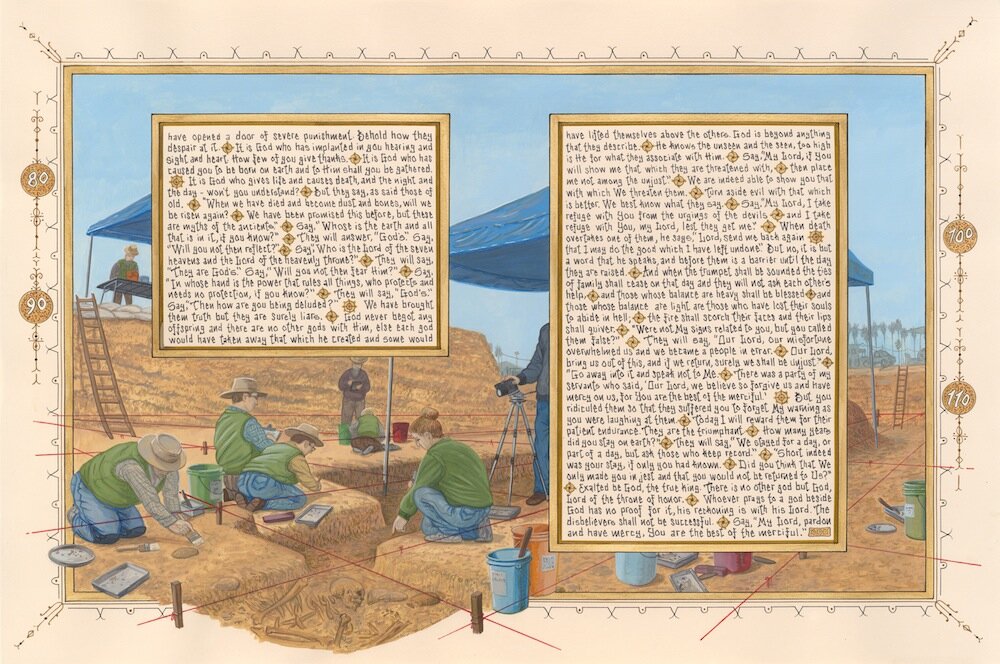

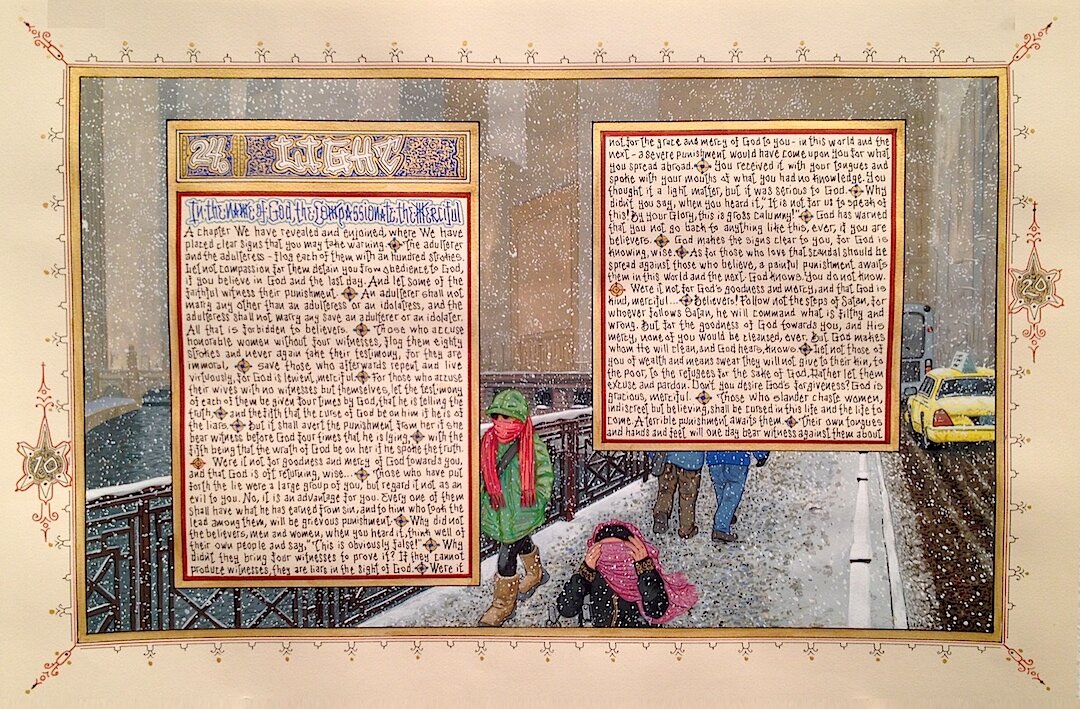

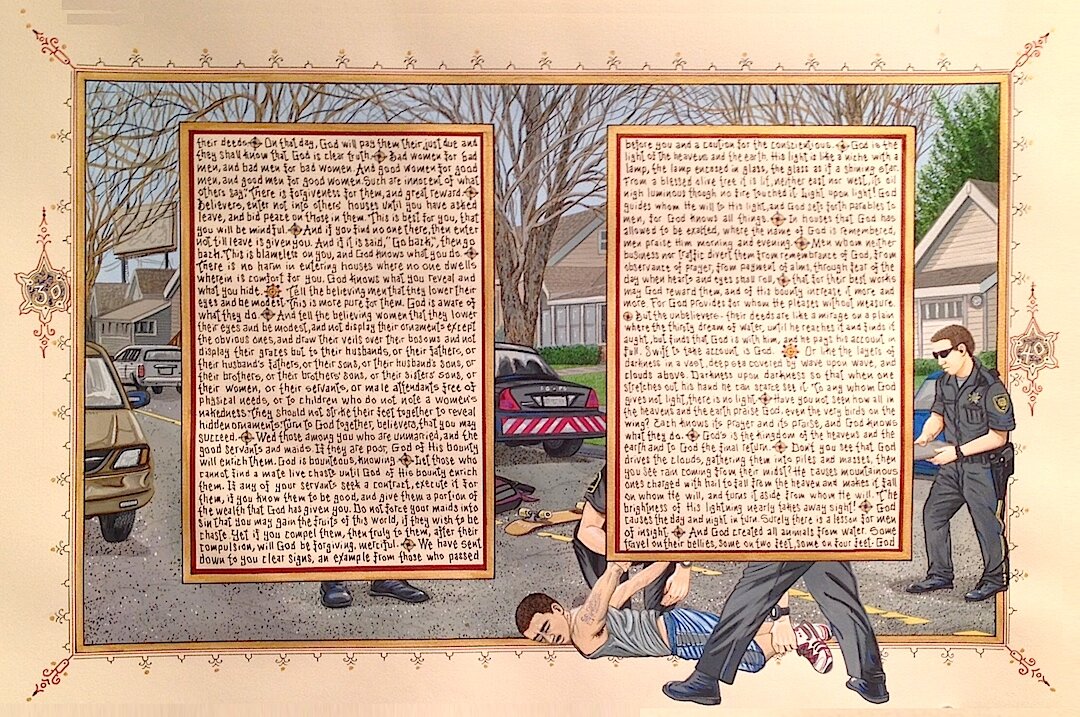

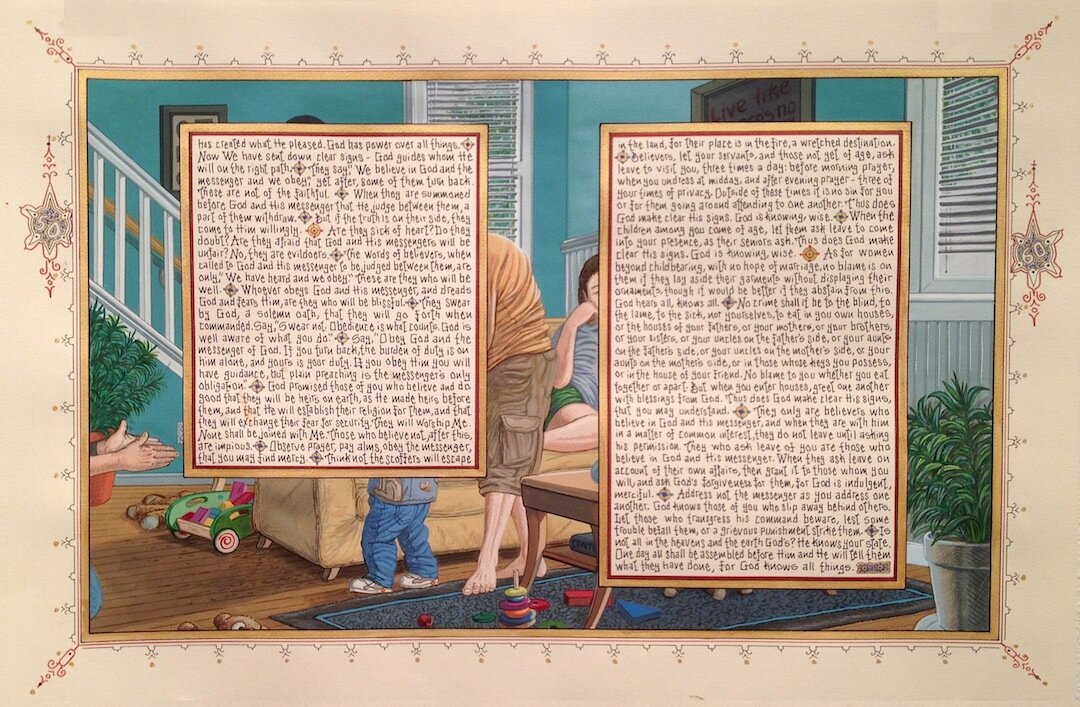

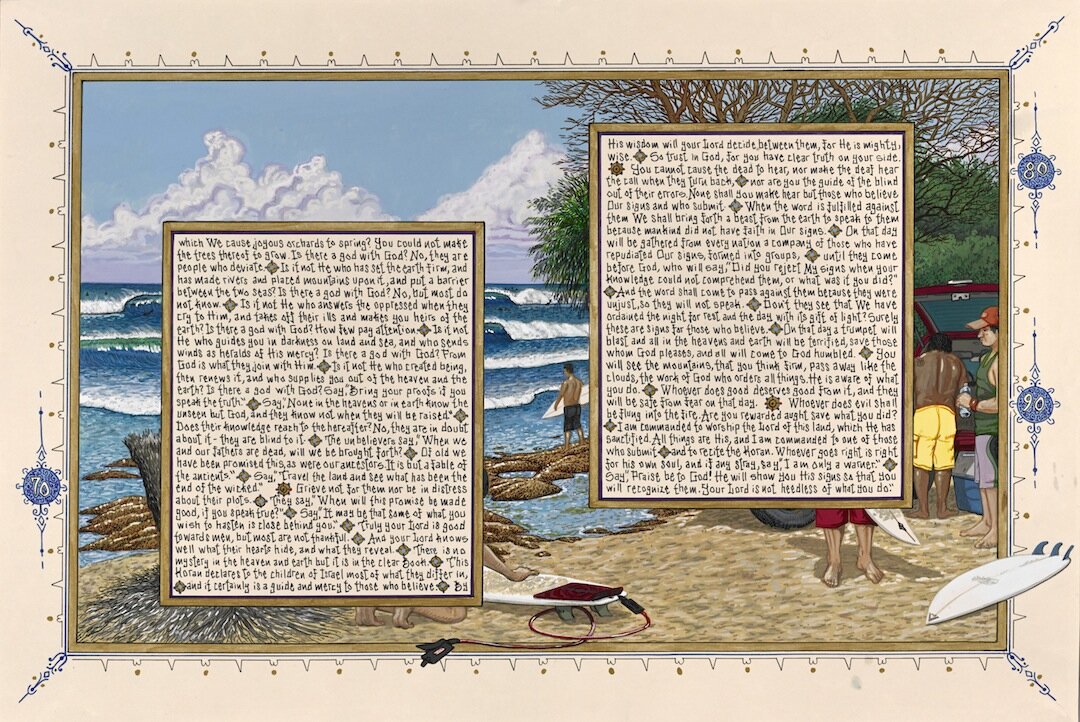

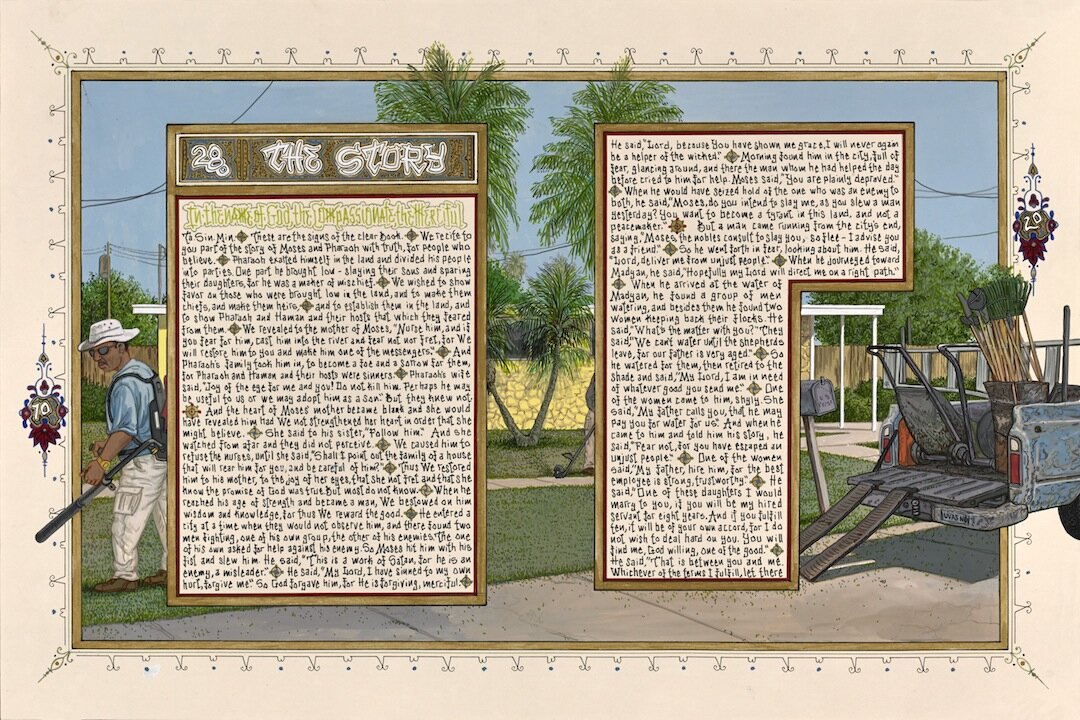

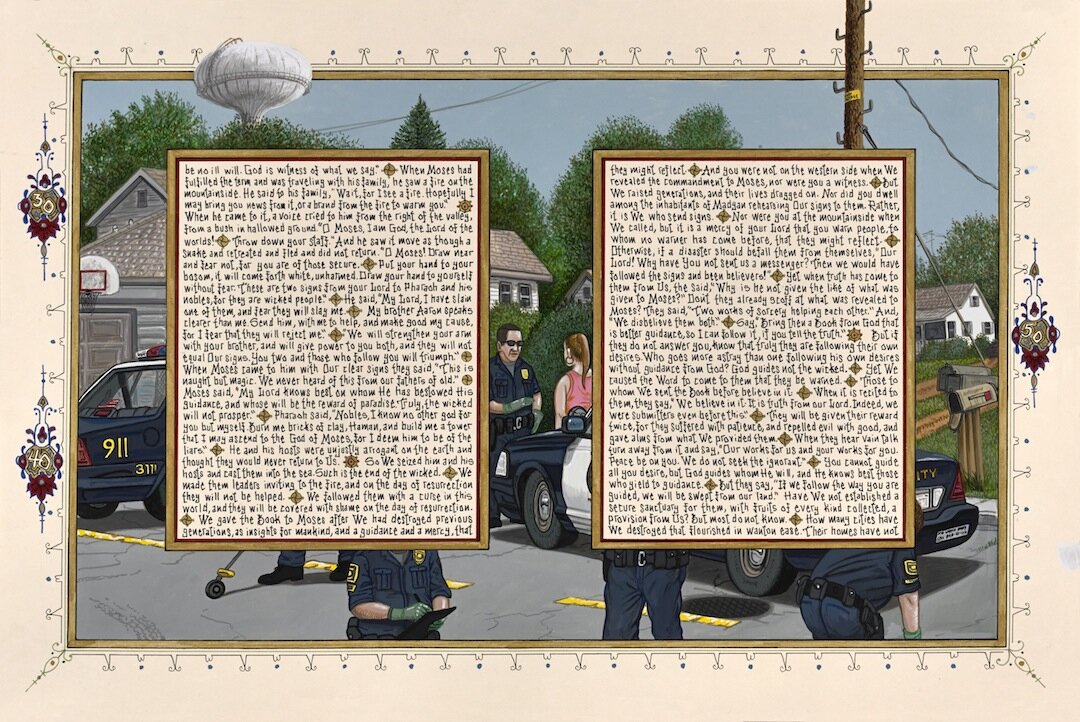

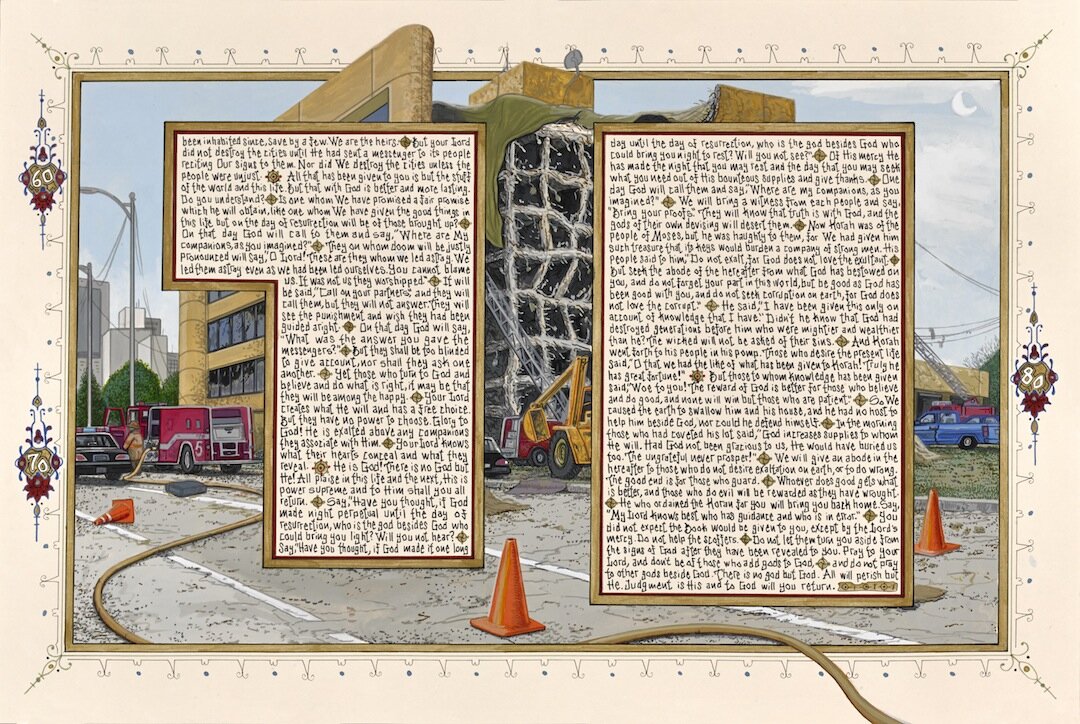

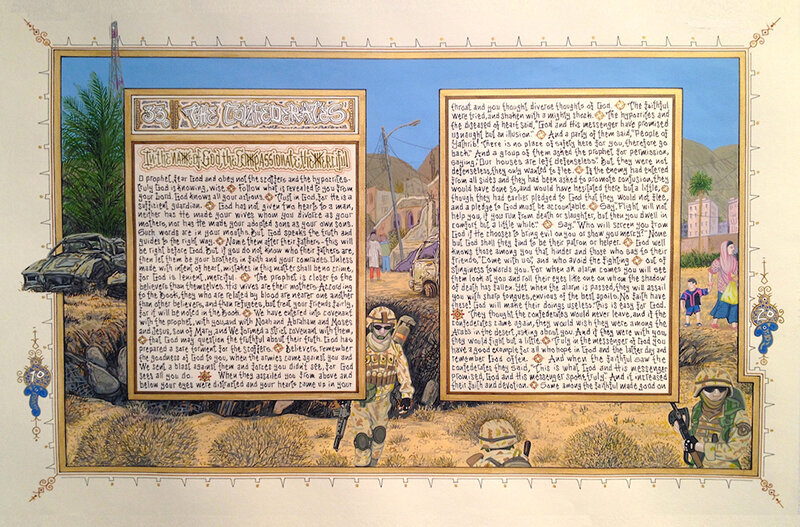

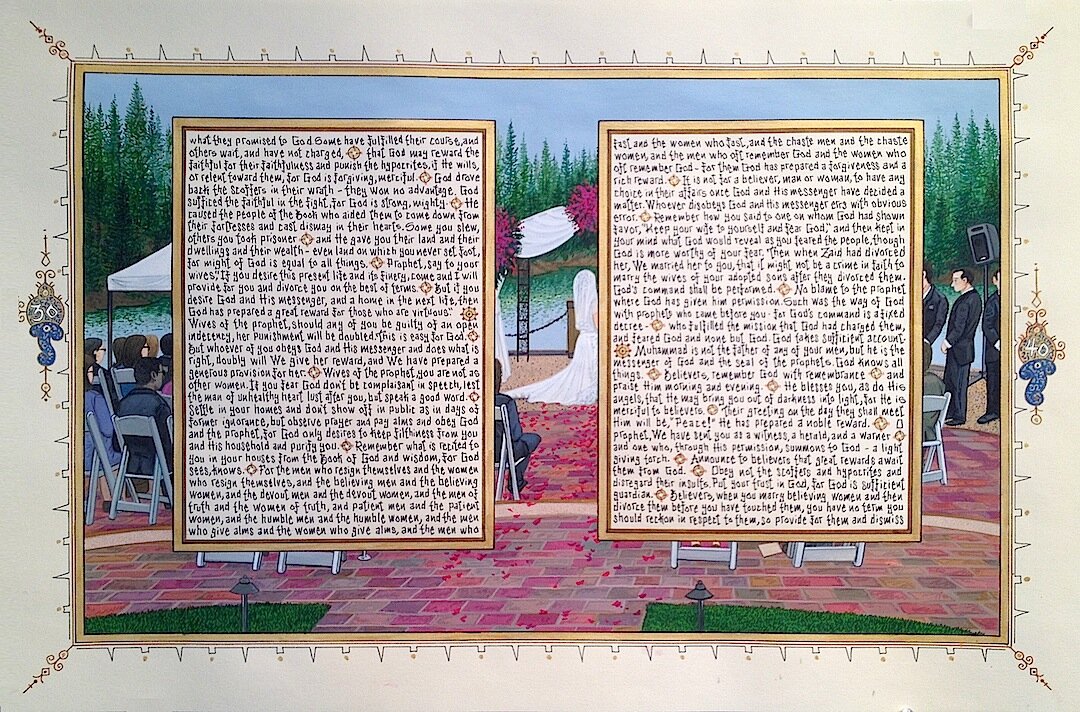

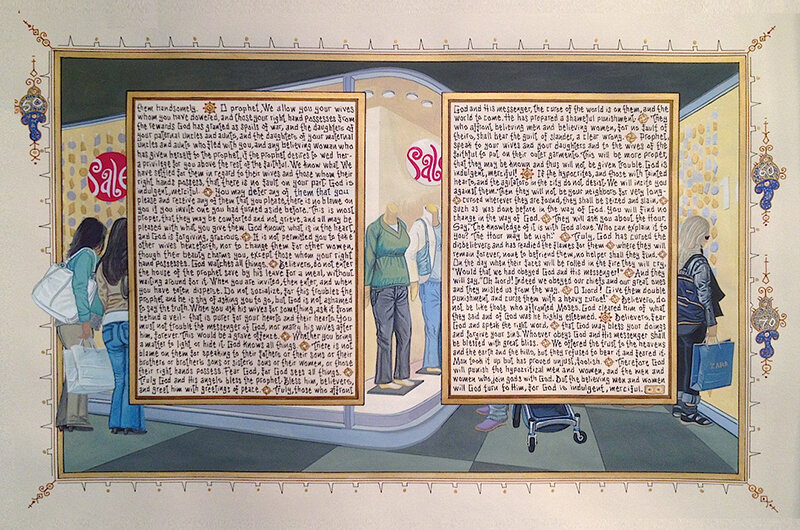

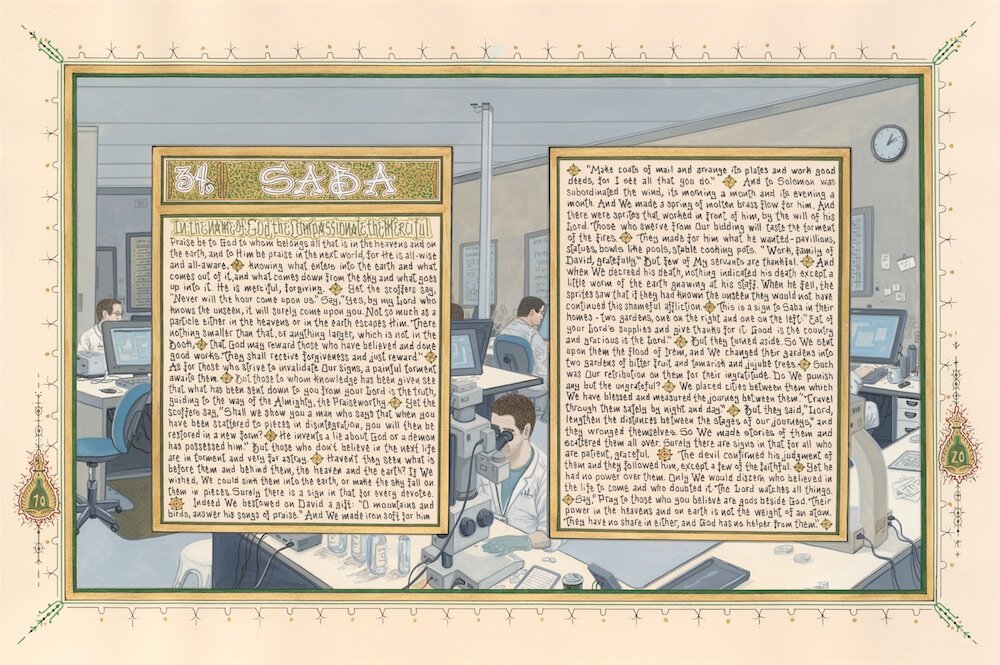

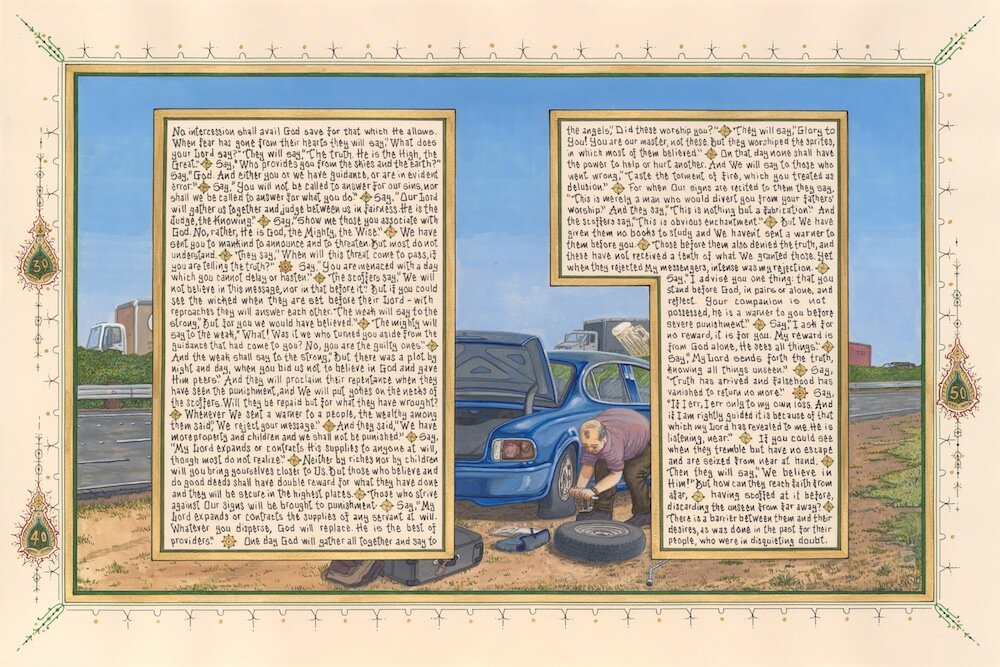

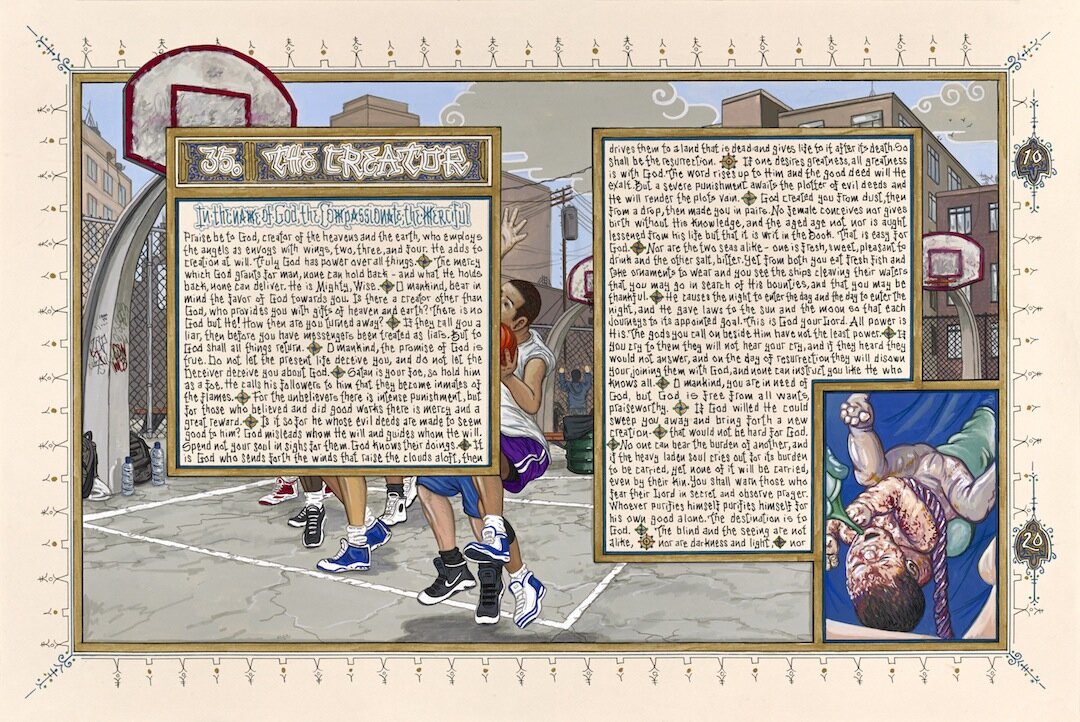

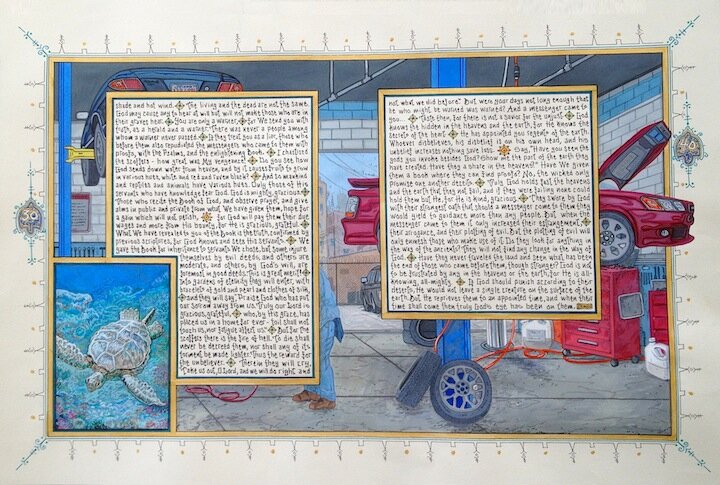

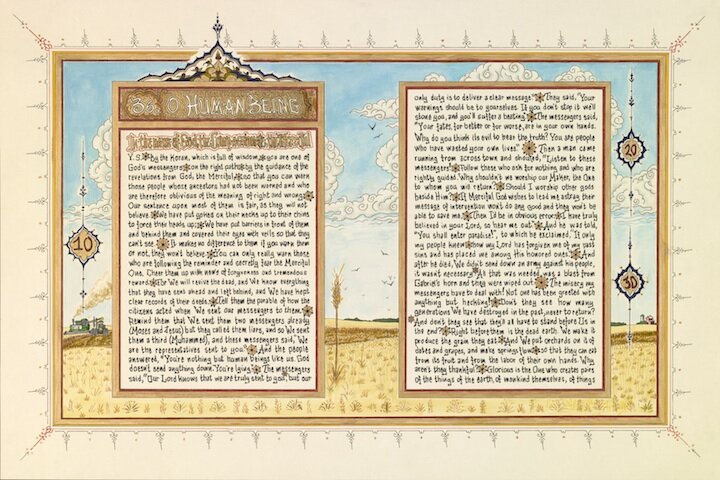

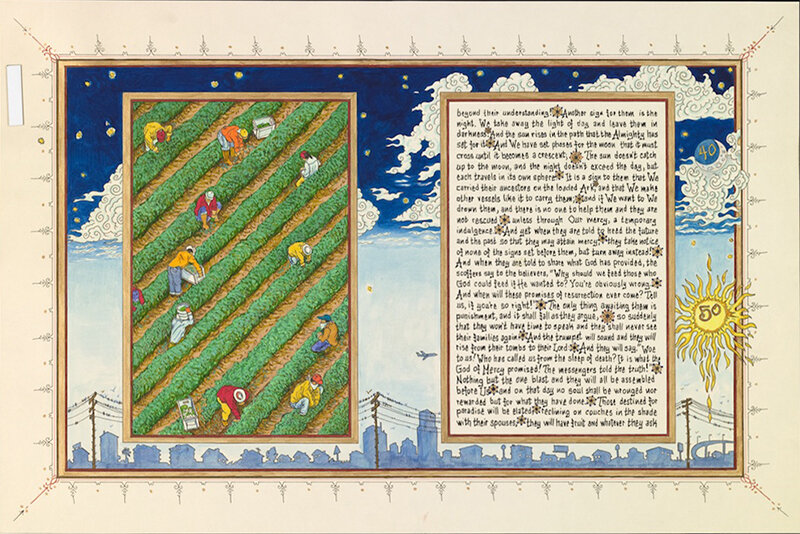

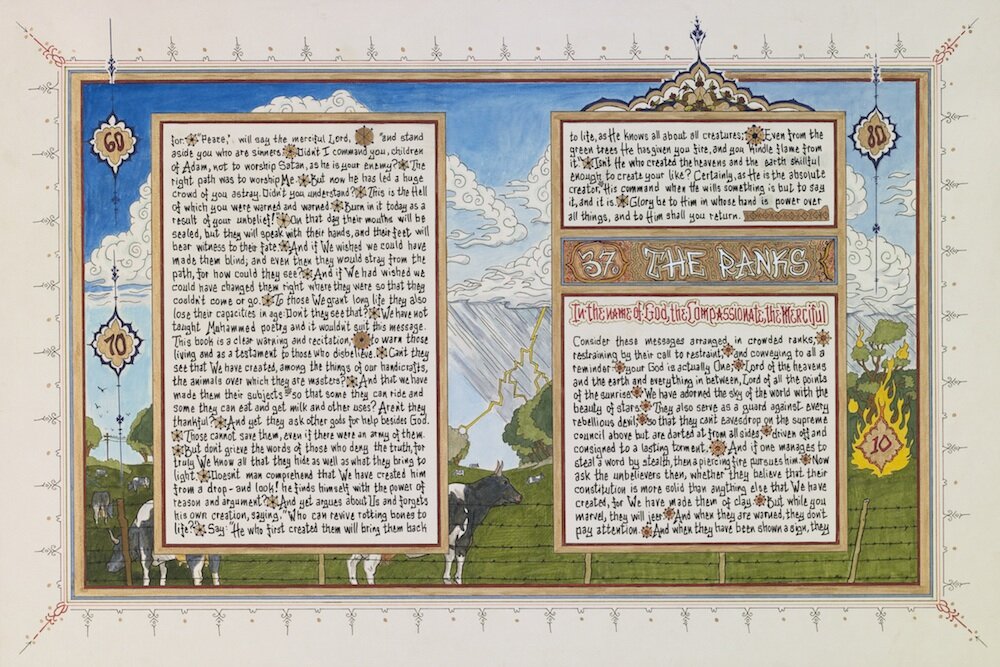

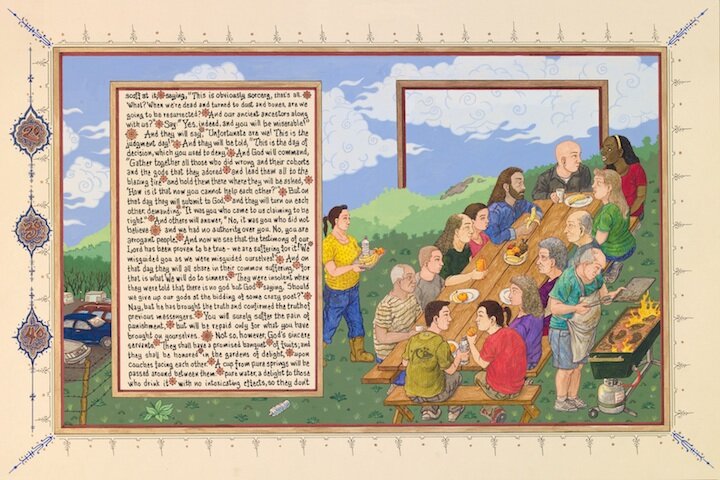

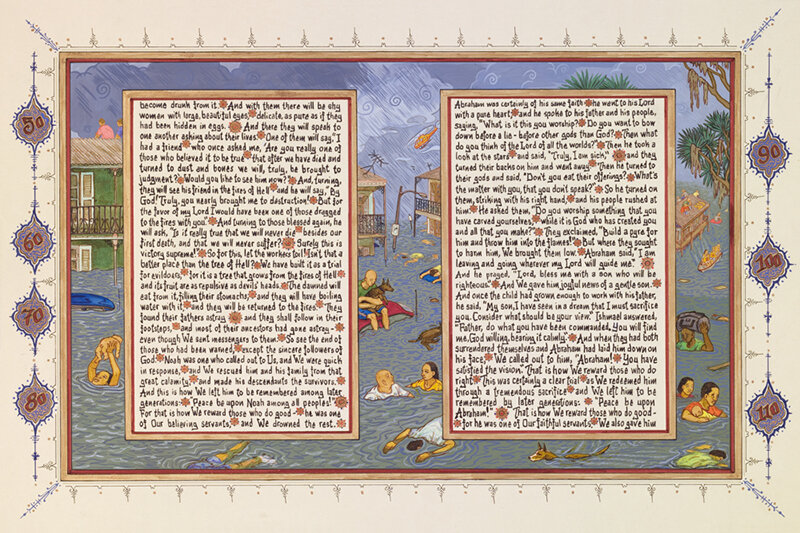

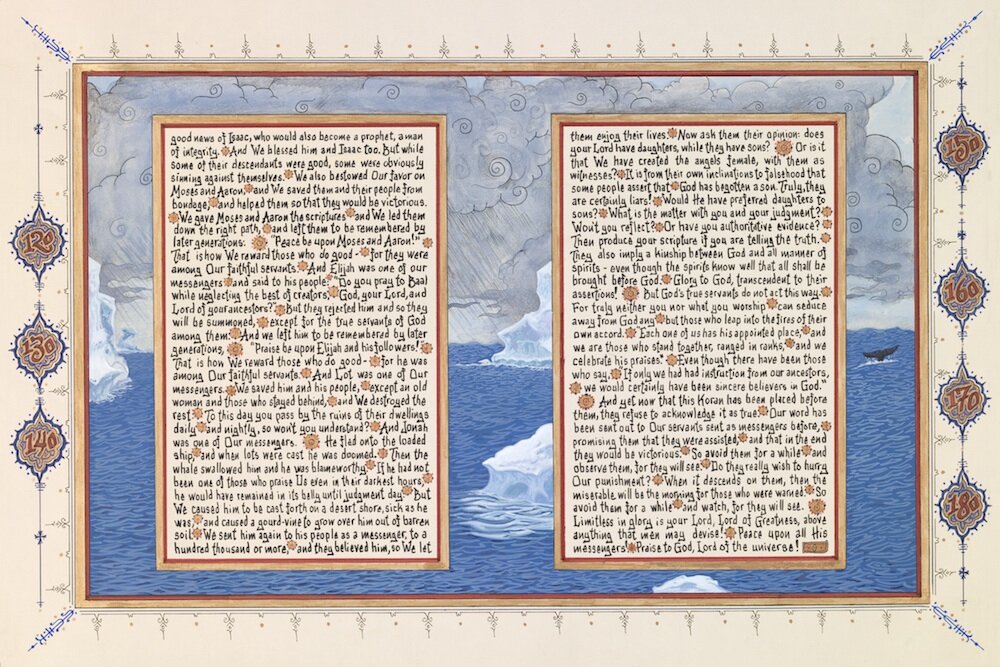

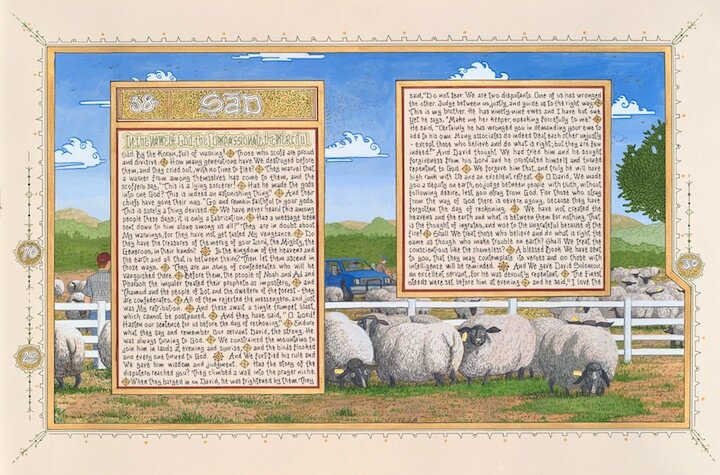

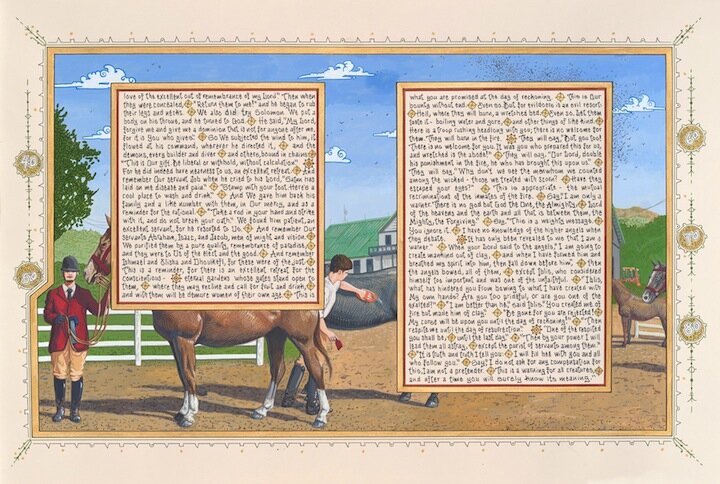

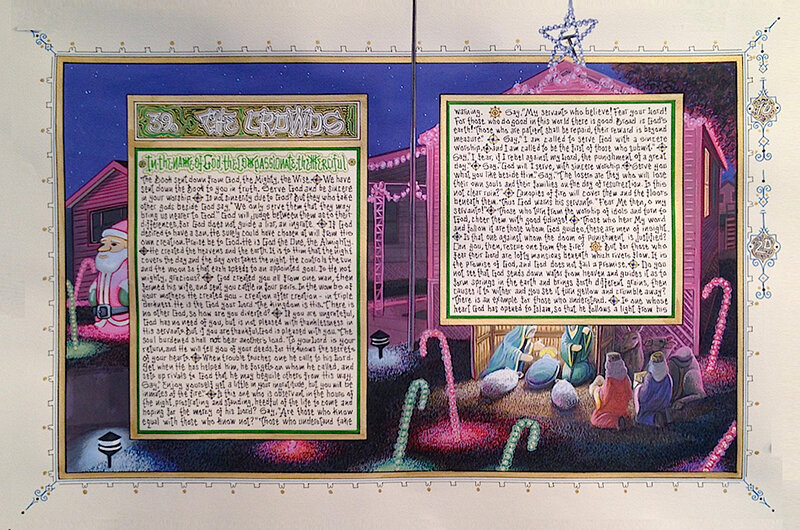

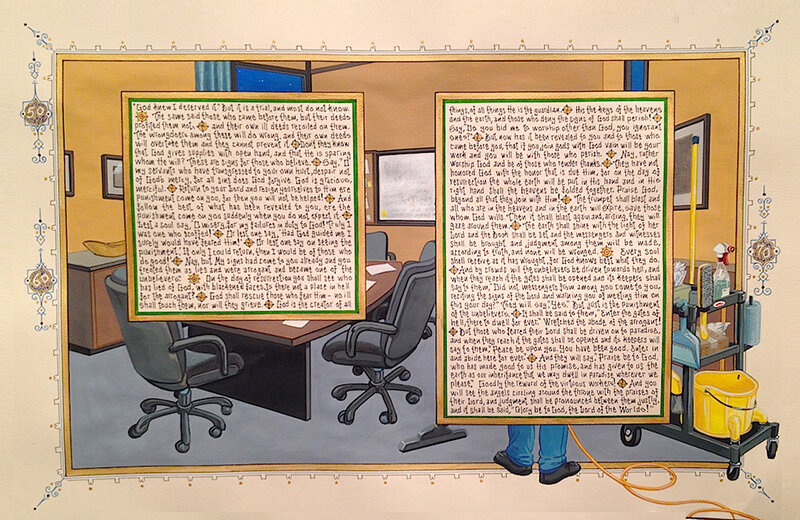

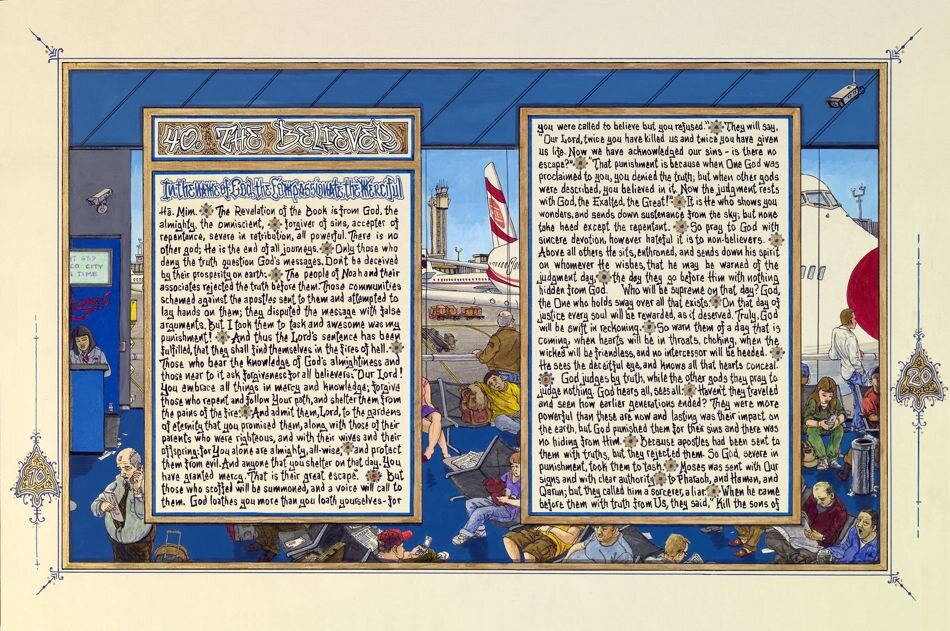

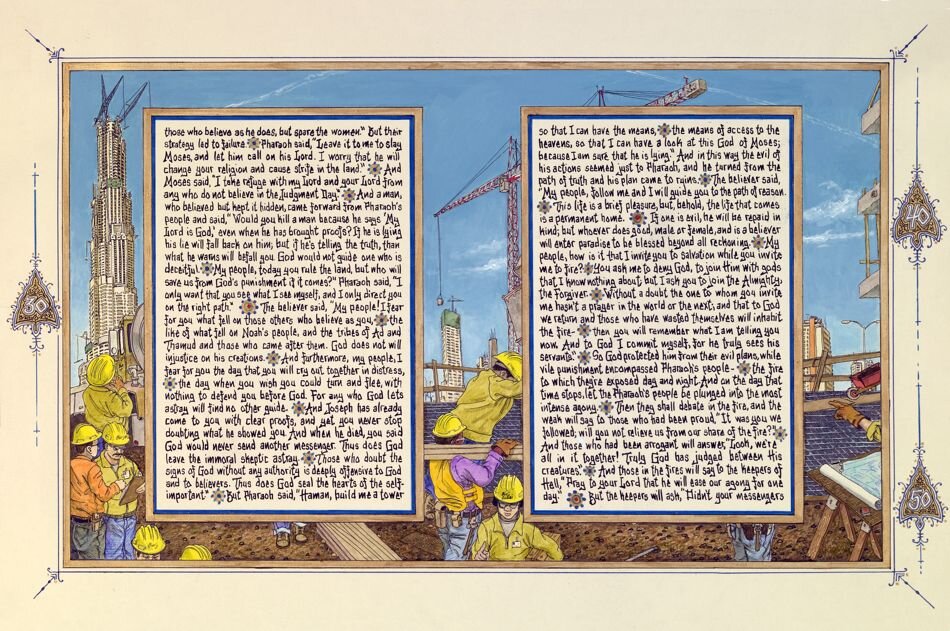

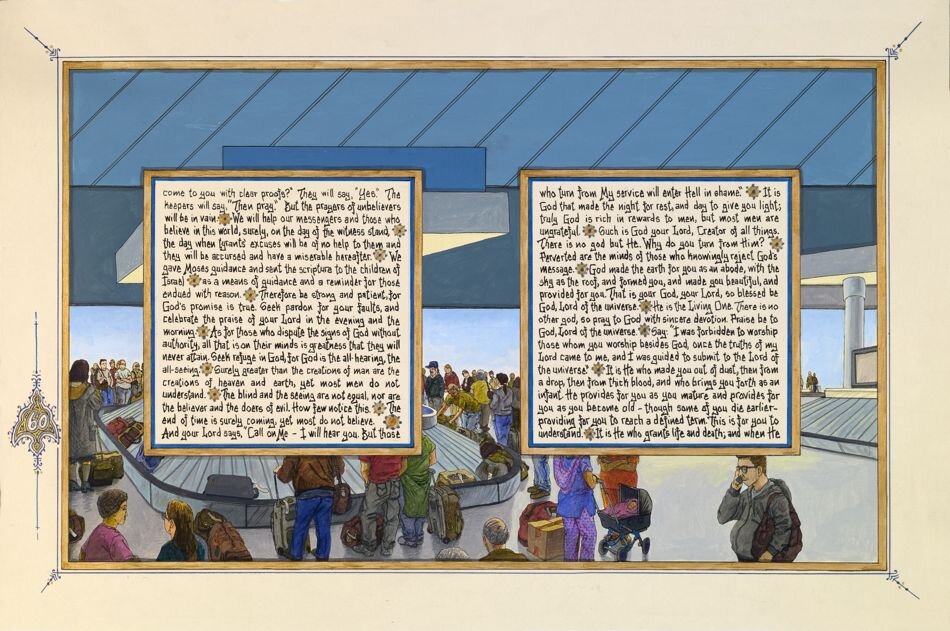

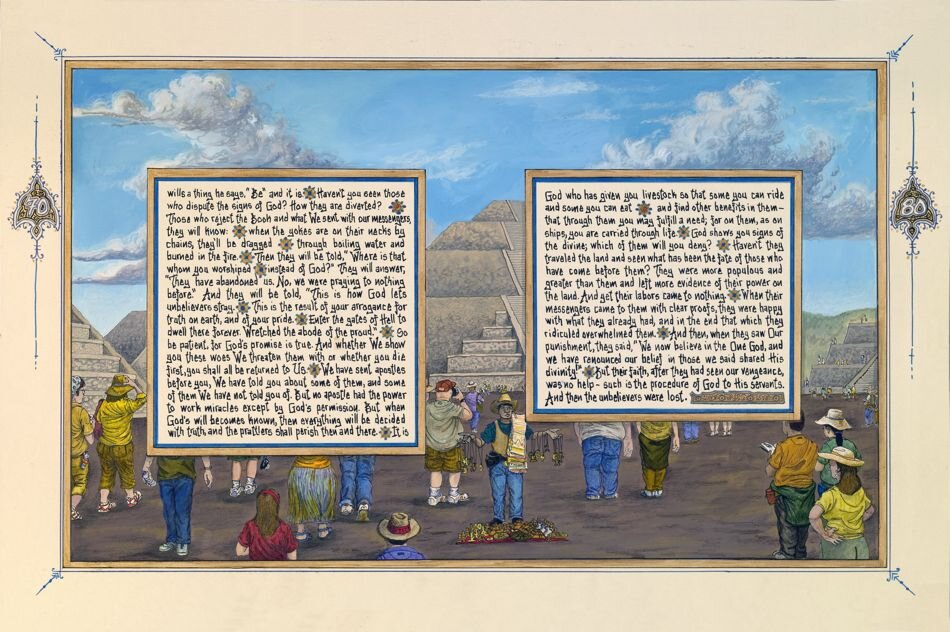

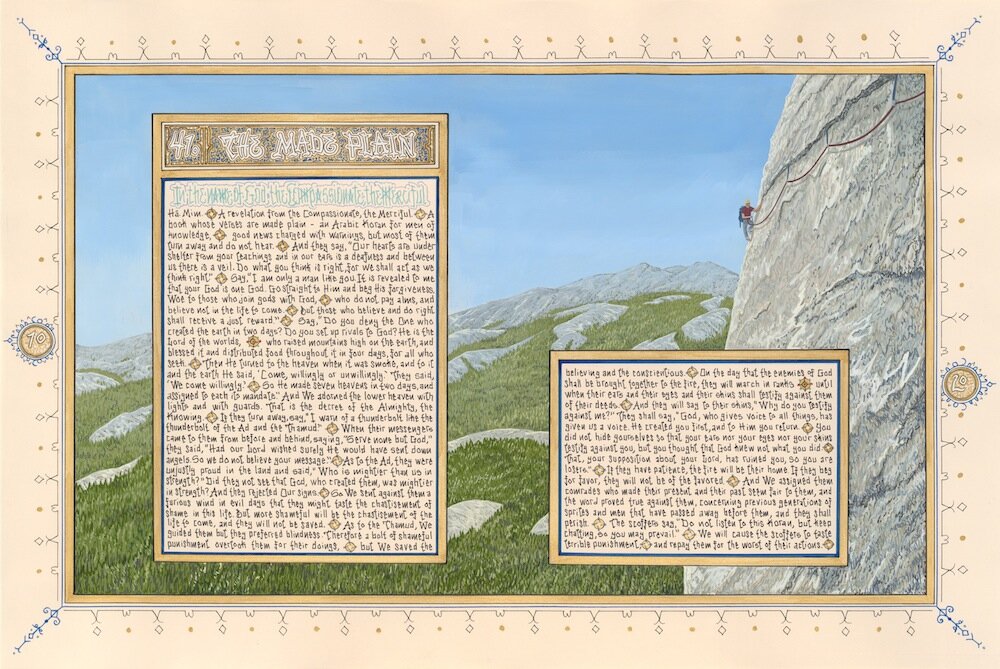

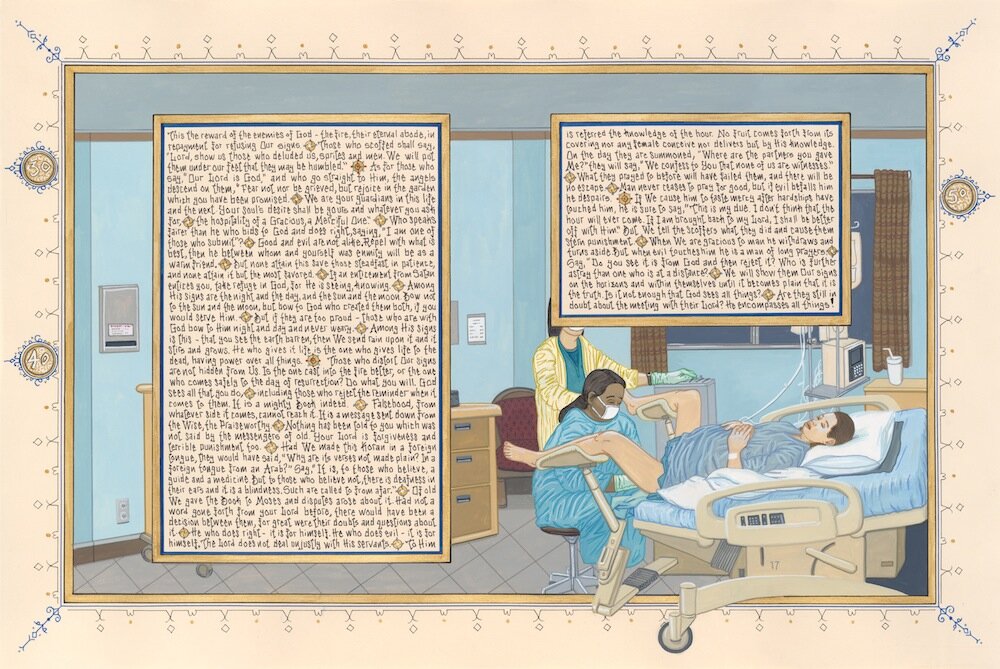

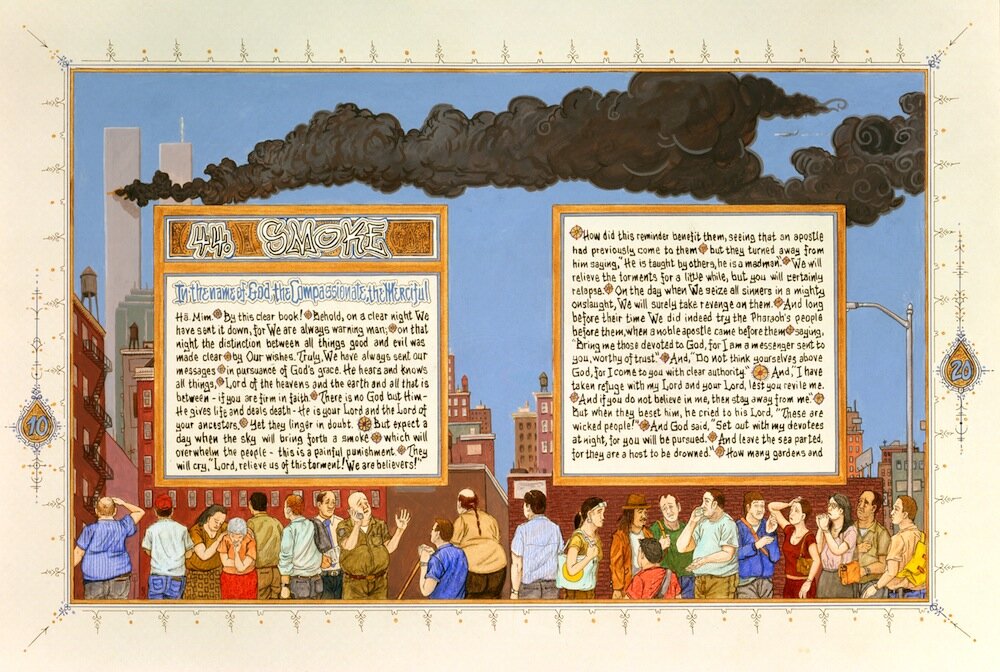

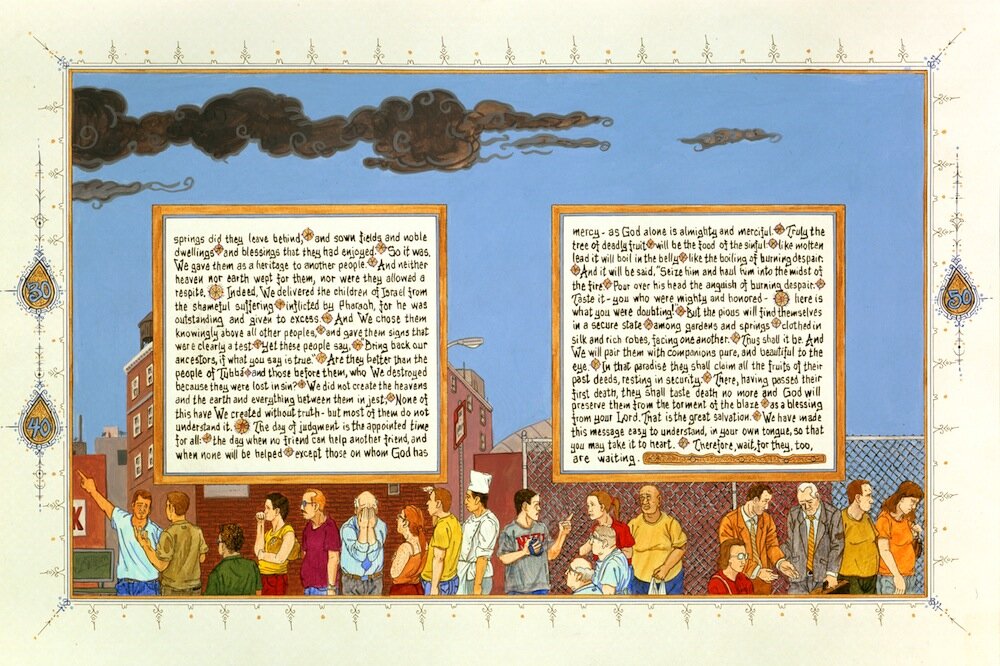

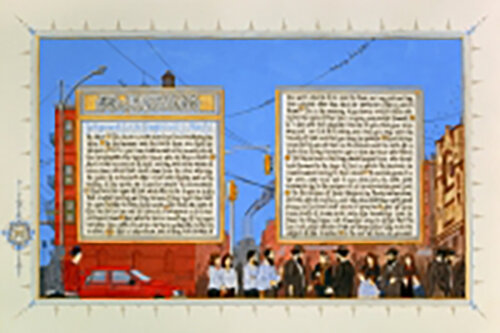

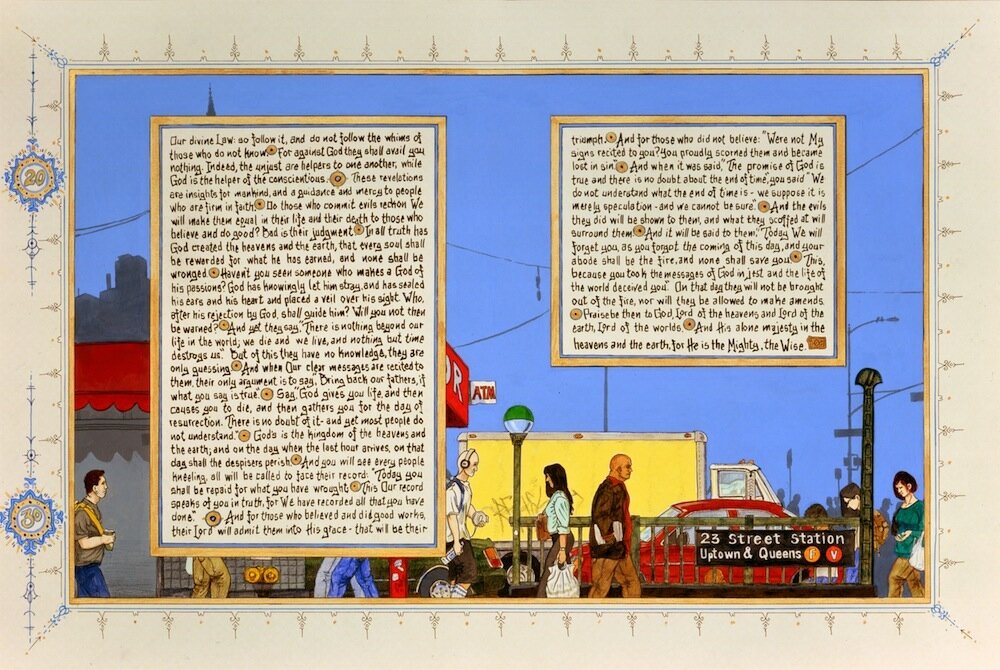

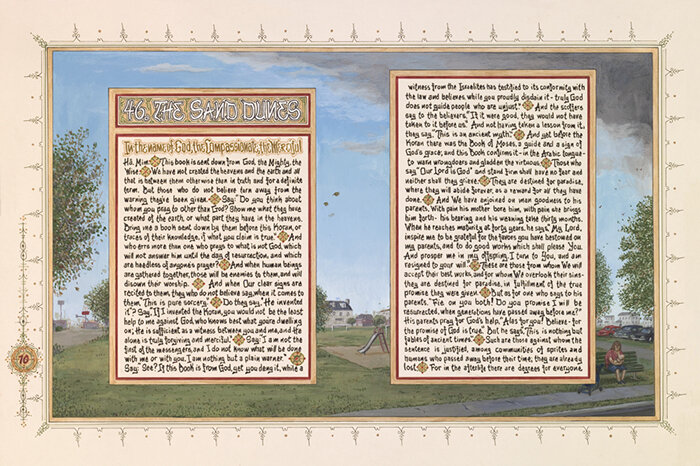

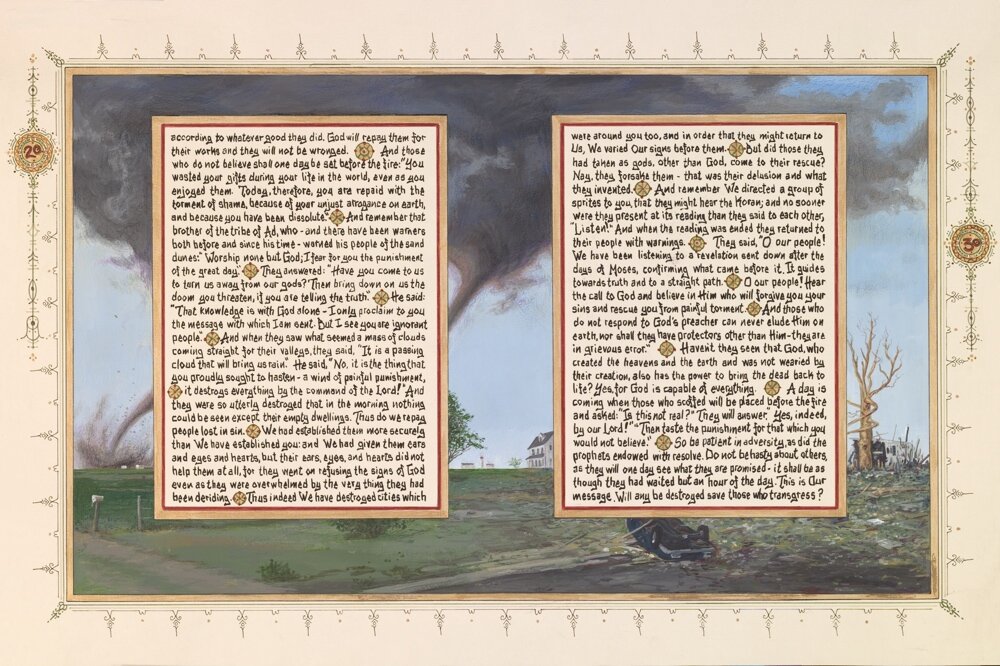

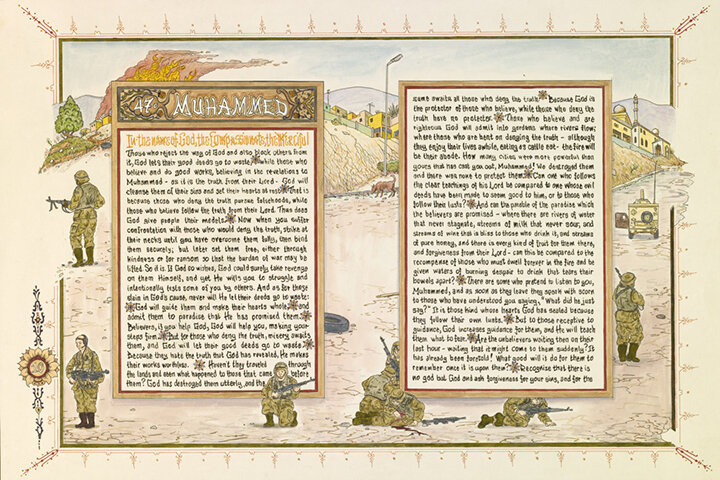

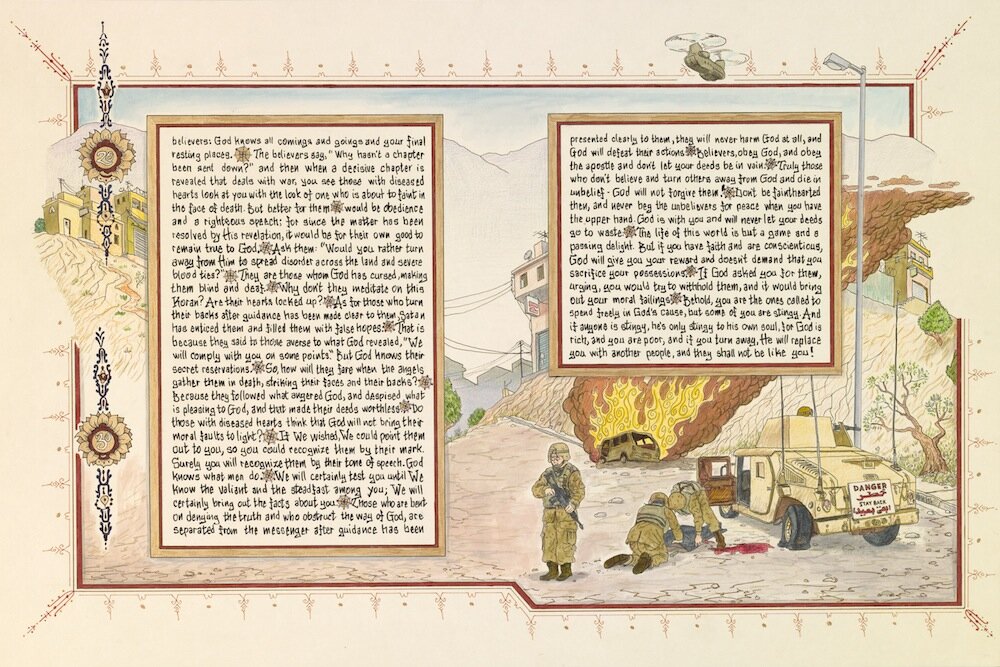

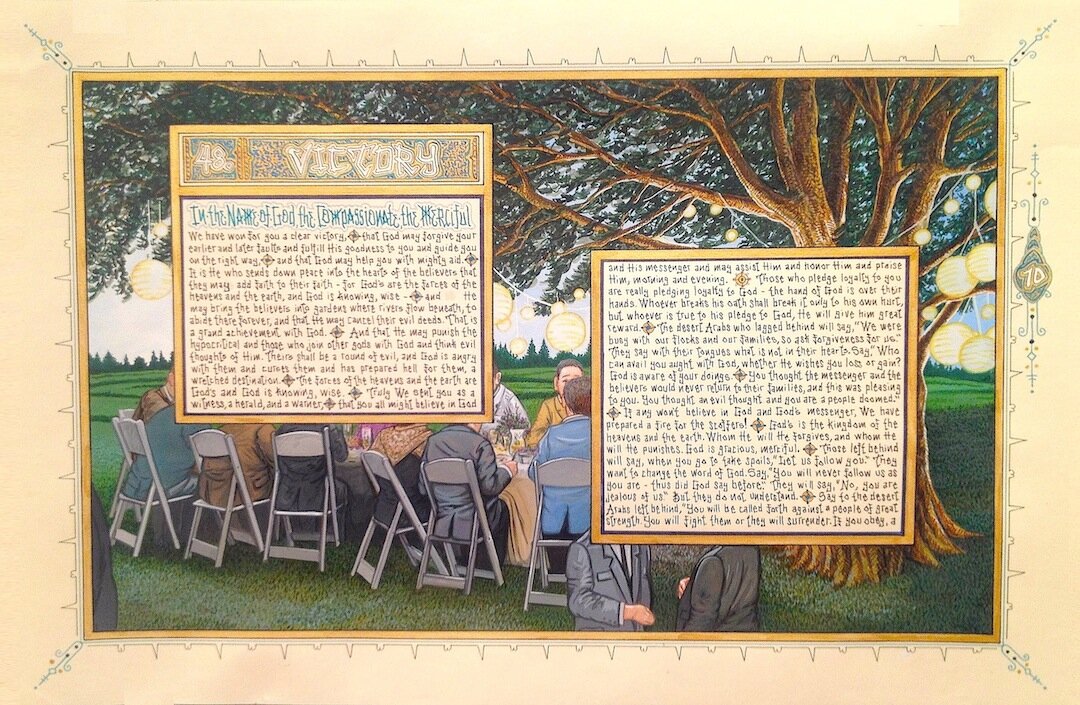

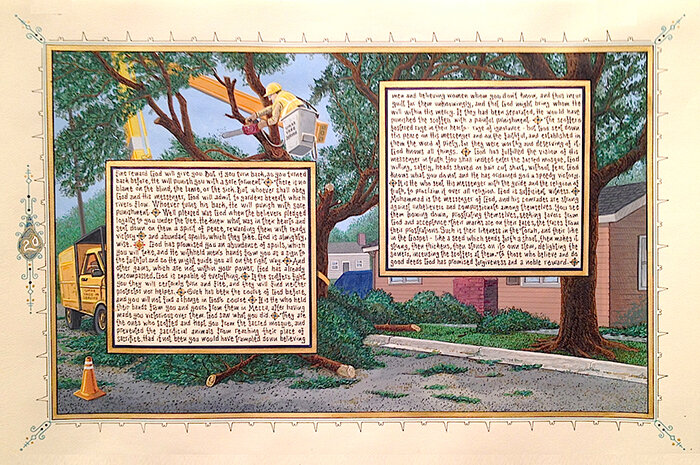

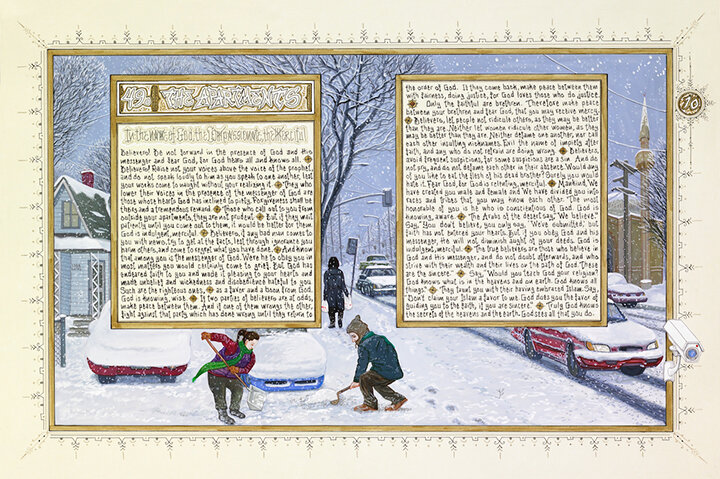

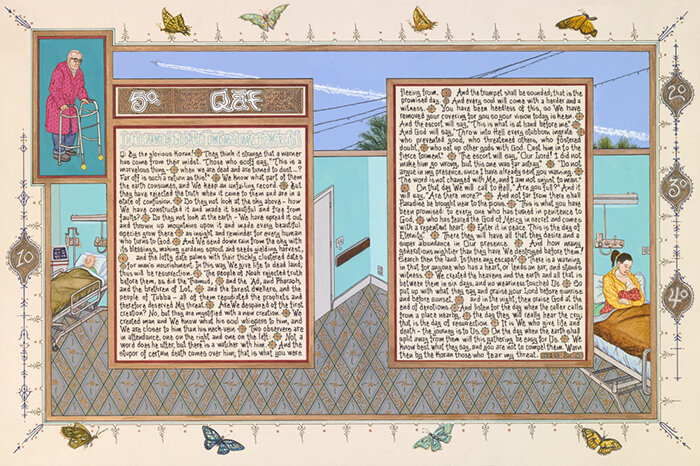

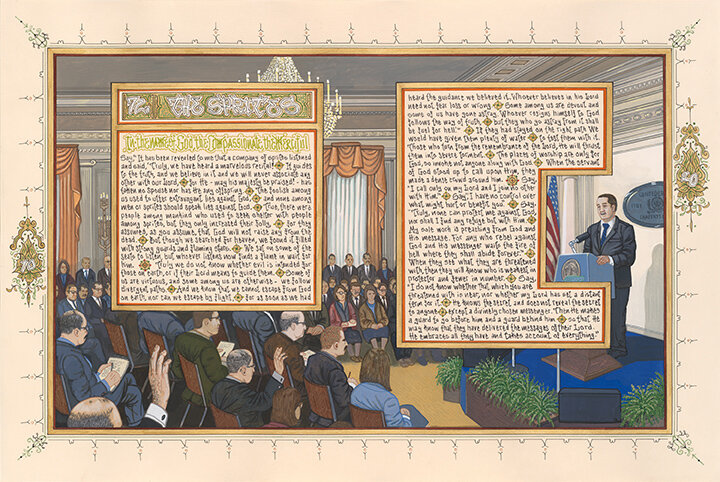

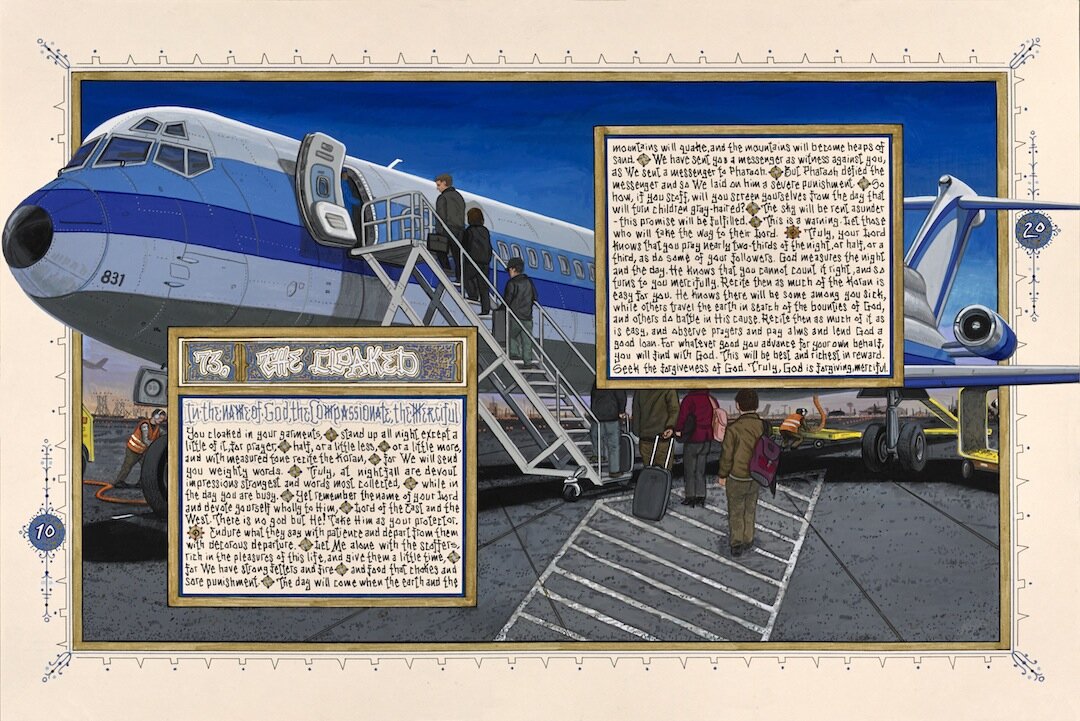

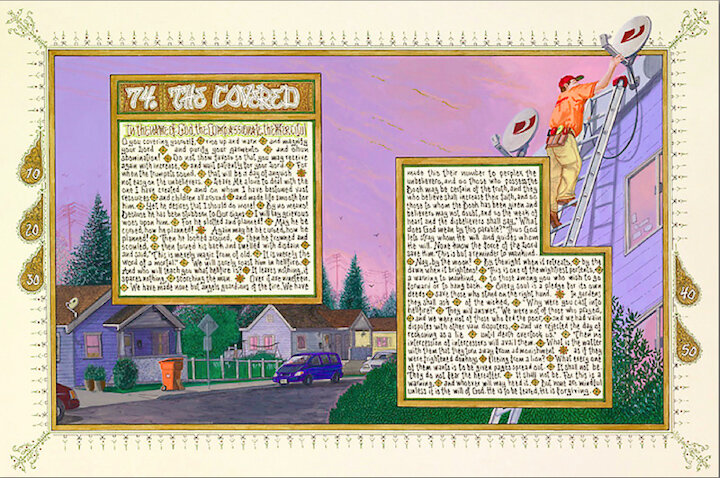

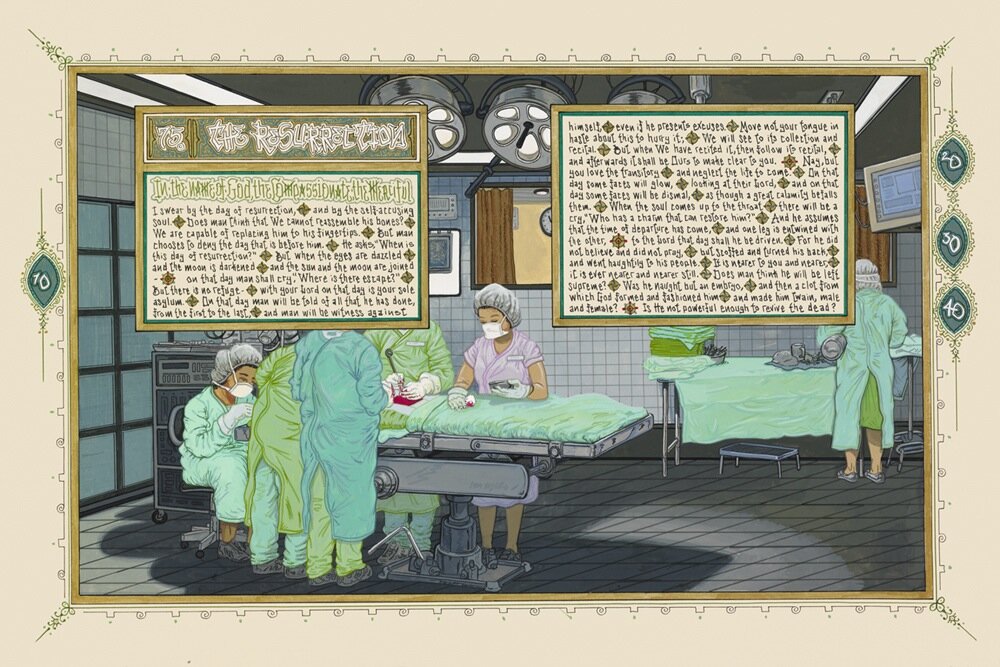

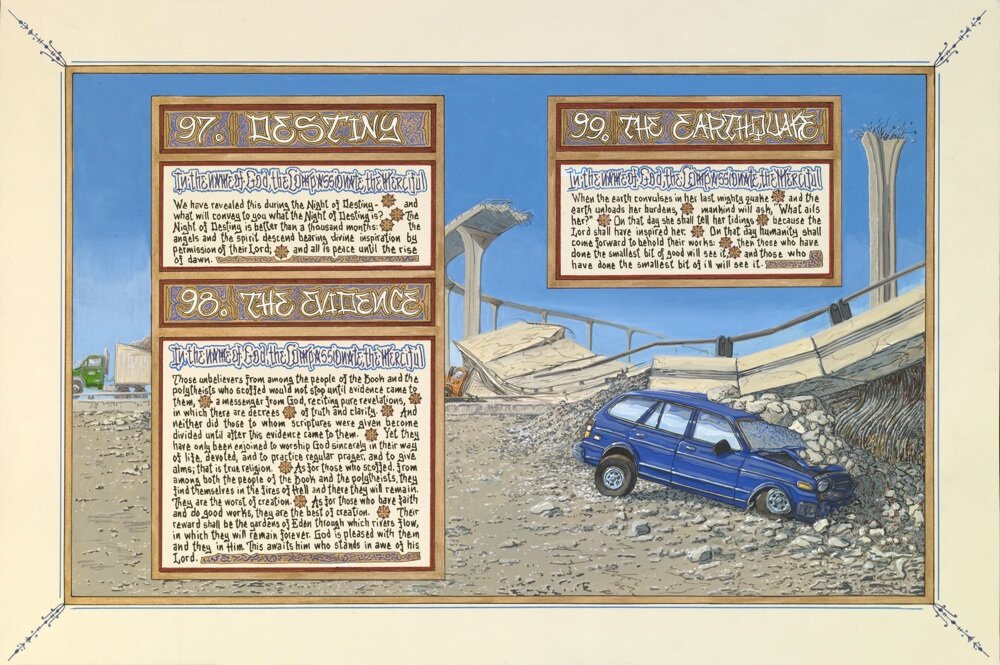

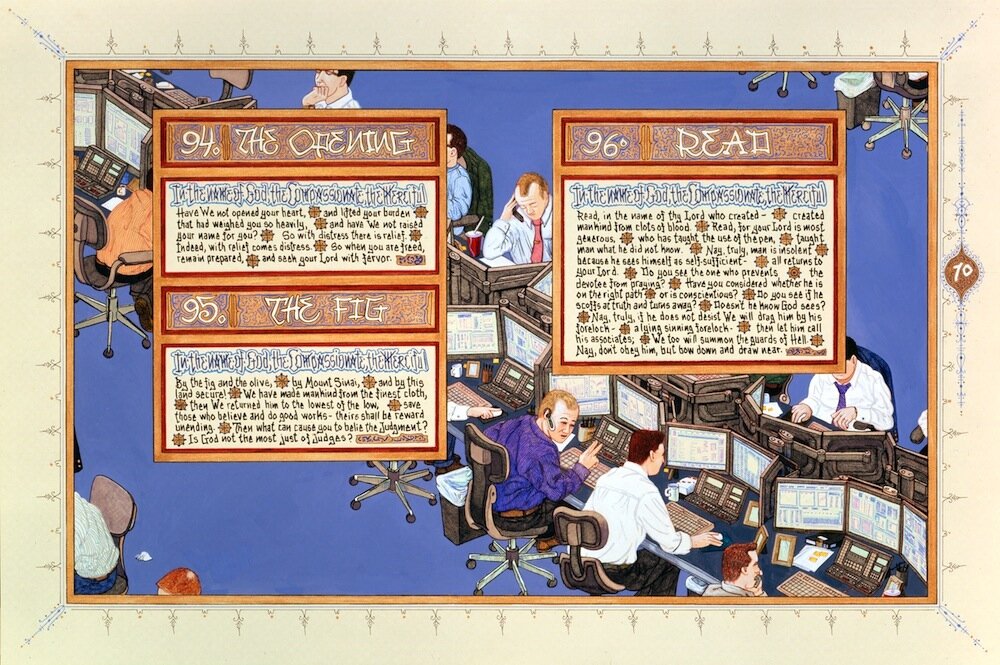

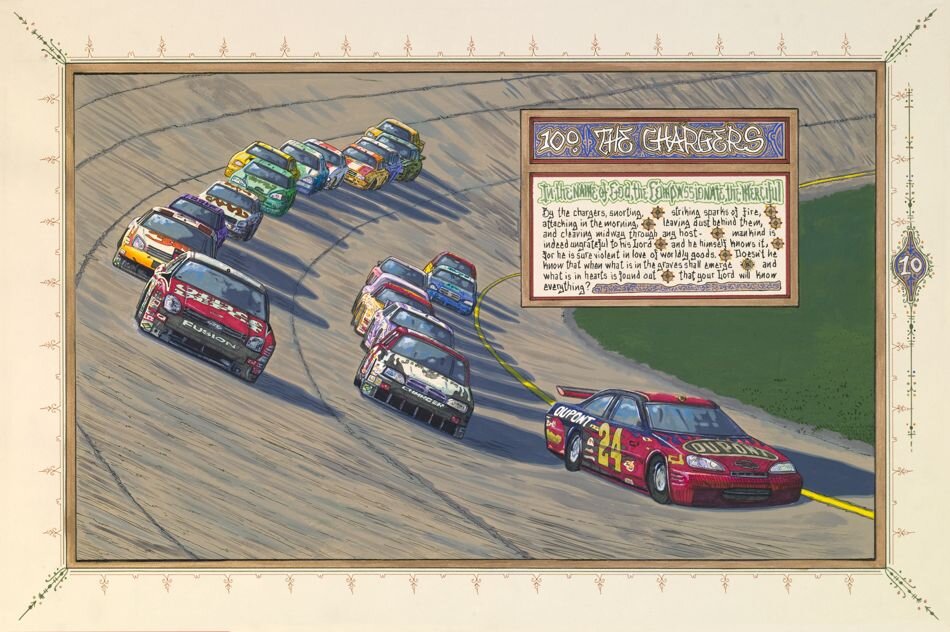

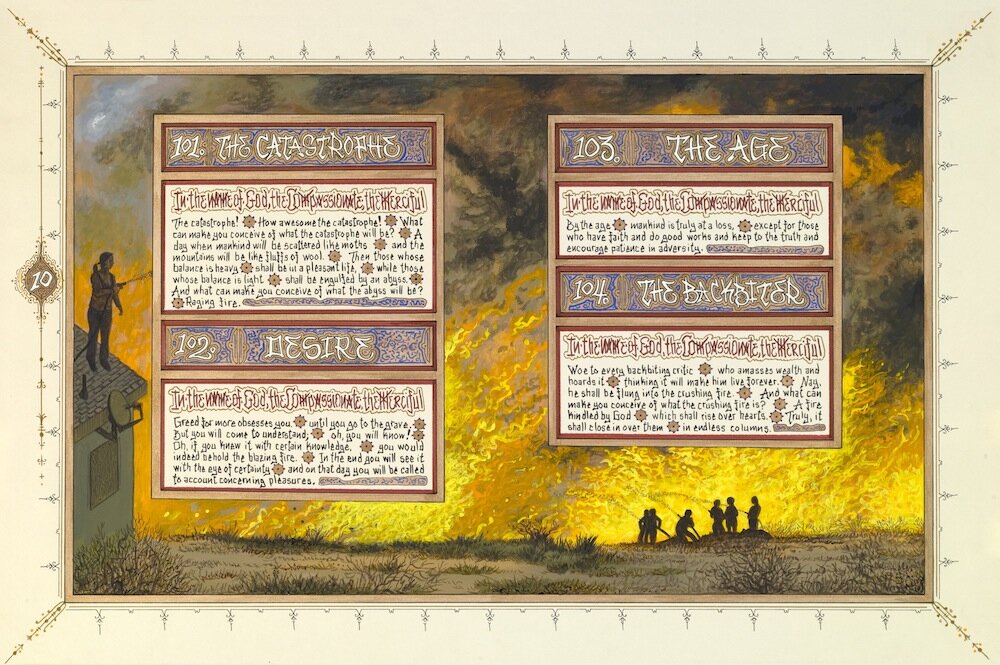

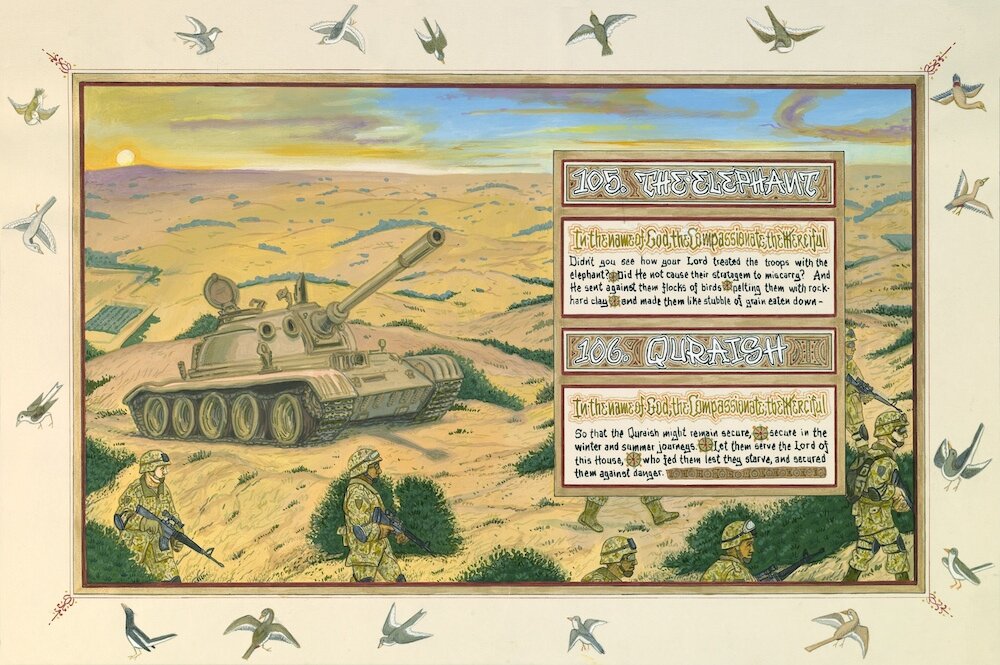

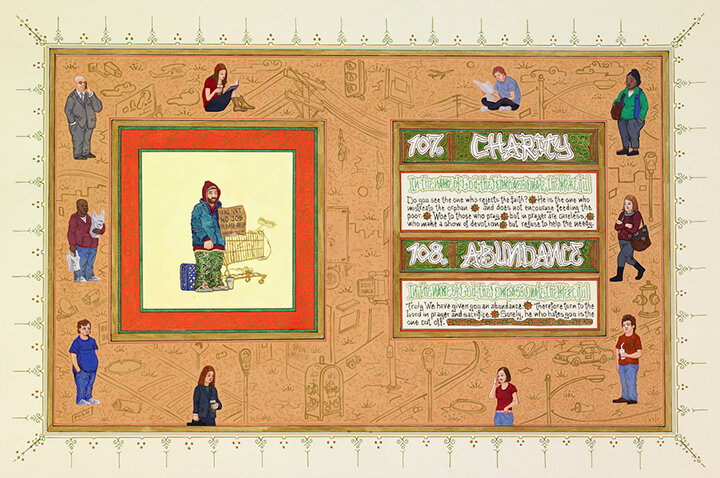

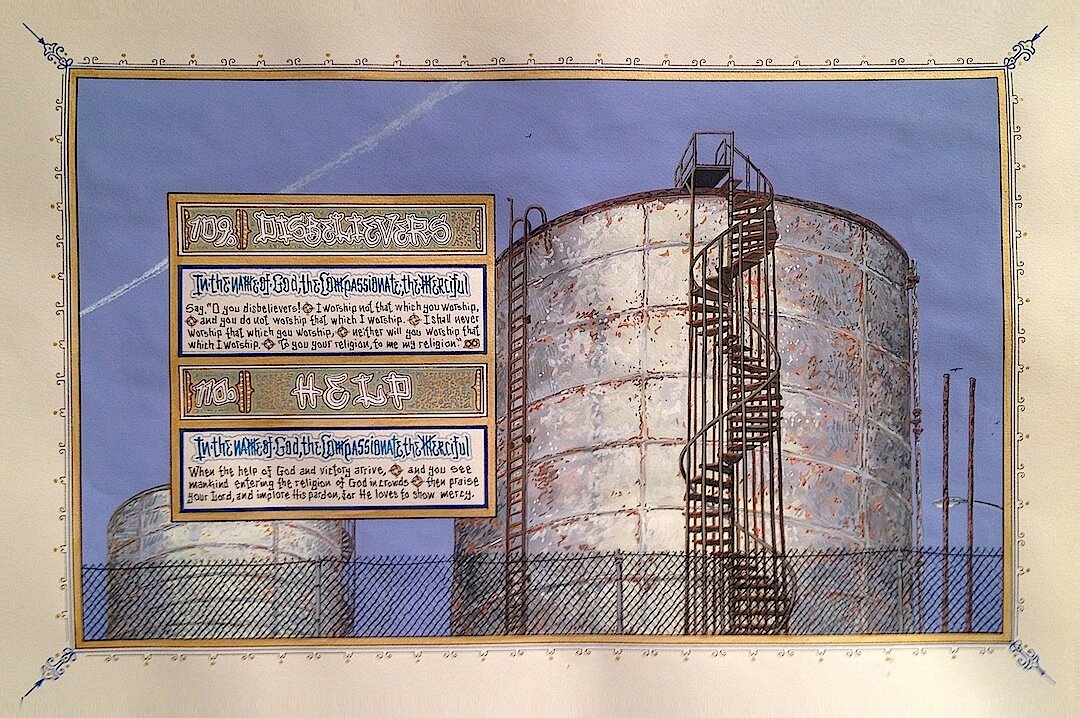

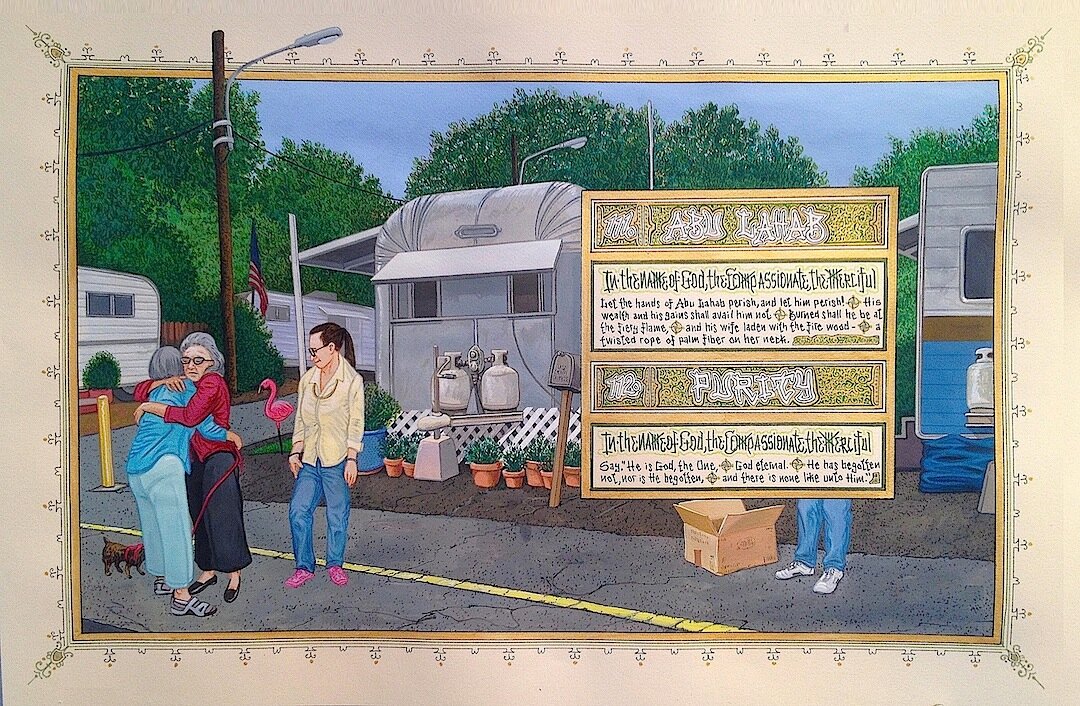

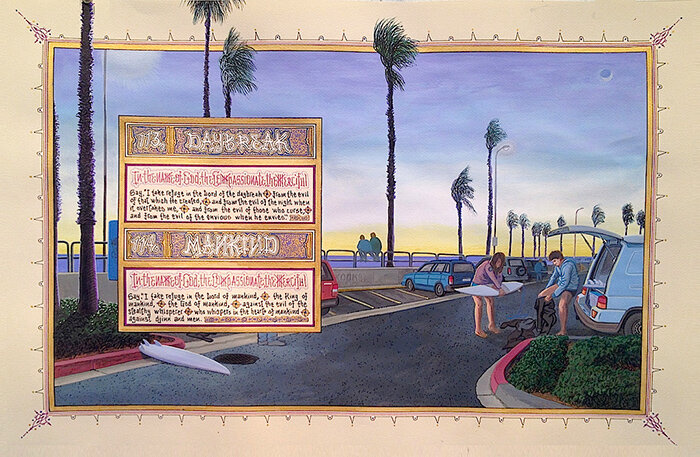

A project to hand-transcribe the entire Qur'an according to historic Islamic traditions and to illuminate the text with relevant scenes from contemporary American life. Nine years in the making, the project was inspired by a decade of extended travel in Islamic regions of the world.

Introduction:

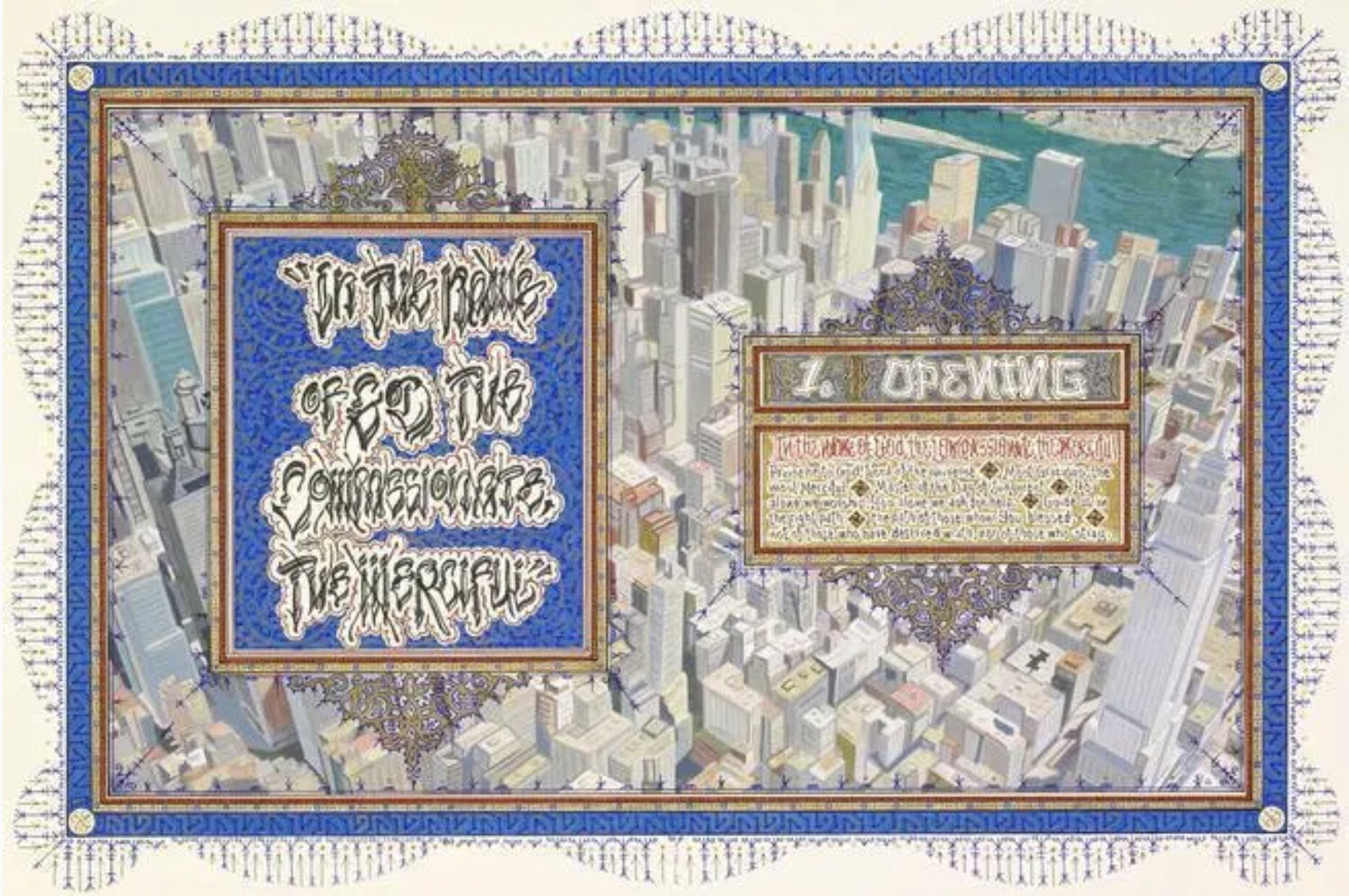

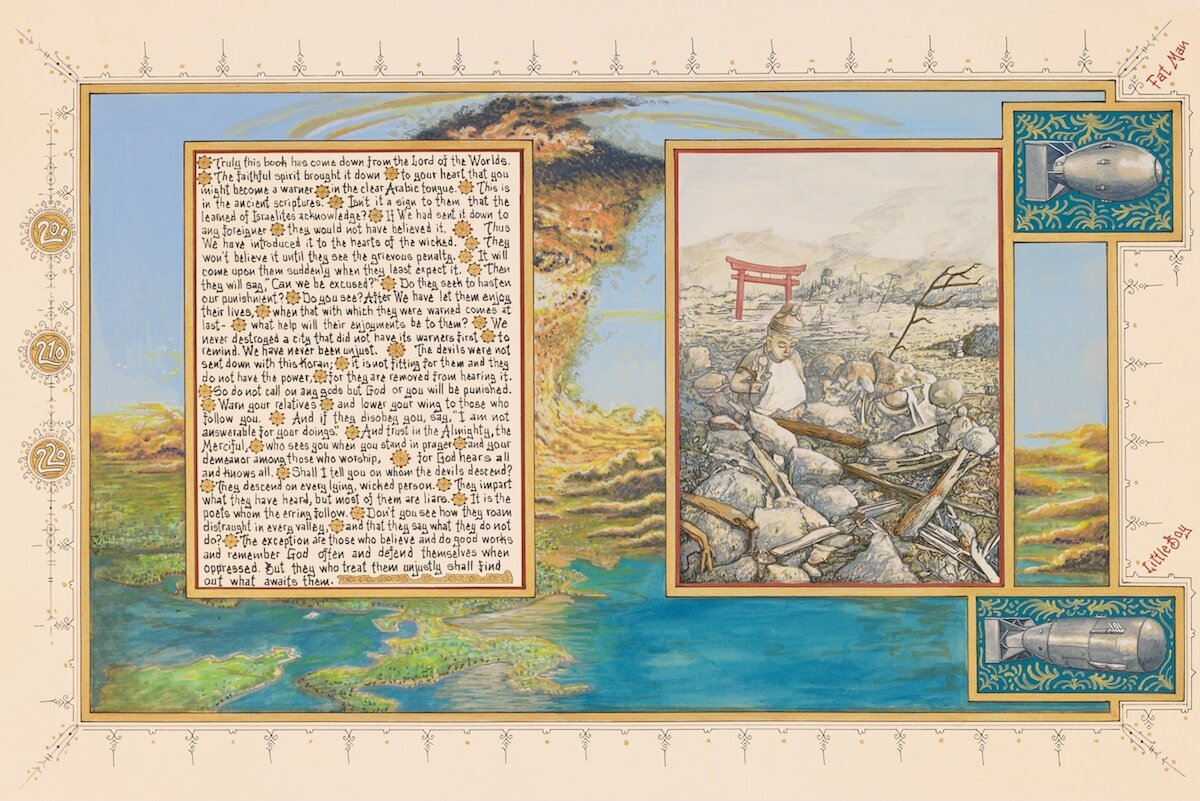

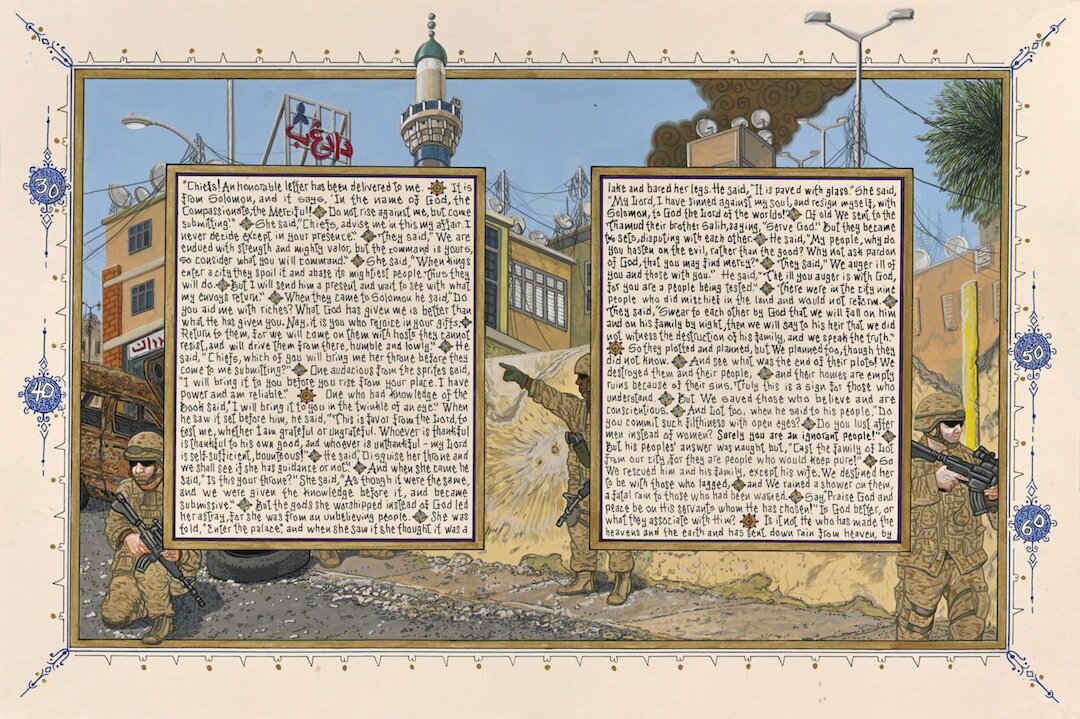

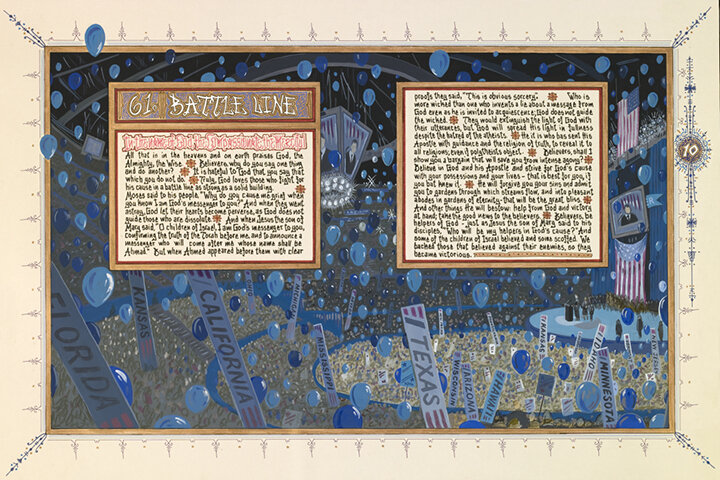

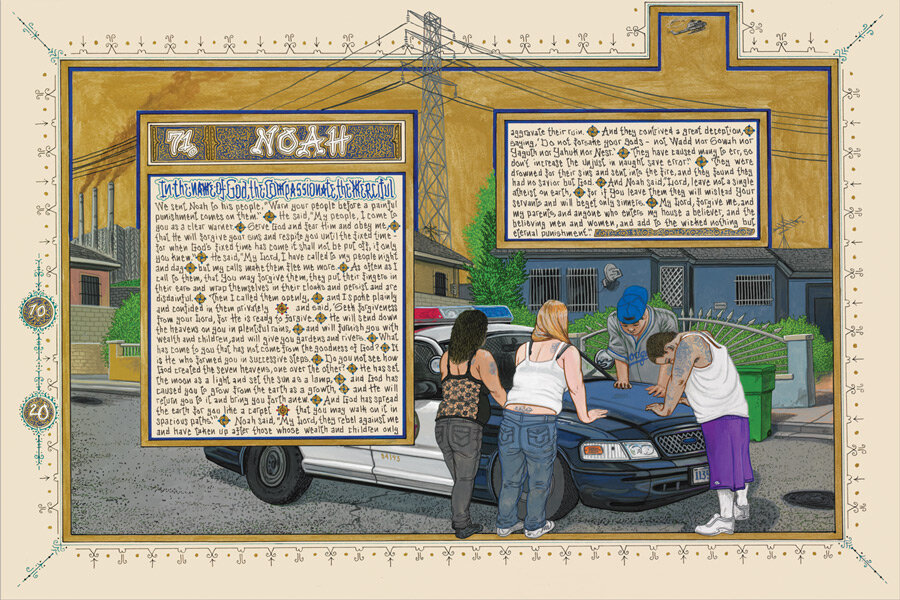

Unlike the Gospels of the New Testament – which relate narratives of Jesus’ ministry on earth – the Holy Qur’an is believed to be the verbatim words of God as communicated through the angel Gabriel to Muhammad in the 7th Century CE. Collected together and grouped generally according to length (rather than chronologically), the 114 chapters (“suras”) form a collection of sermon-like “revelations” that are the fundamental text of Islam, the fastest growing religion in America. At a time when the United States was involved in two wars against Islamic nations and declared itself to be in a cultural and philosophical struggle against Islamic extremists, American artist Sandow Birk’s latest project considers the Qur’an as it was intended – as a universal message to humankind. If the Qur’an is indeed a divine message to all peoples, he ponders, what does it mean to an individual American in the 21st Century? How does the message of the Qur’an relate to us, as Americans, in this life, in this time? What is this message that we have spent so much blood and treasure fighting against, and how can the message of the Qur’an be applied to a contemporary American life? In short, what might the Qur’an mean to contemporary Americans?

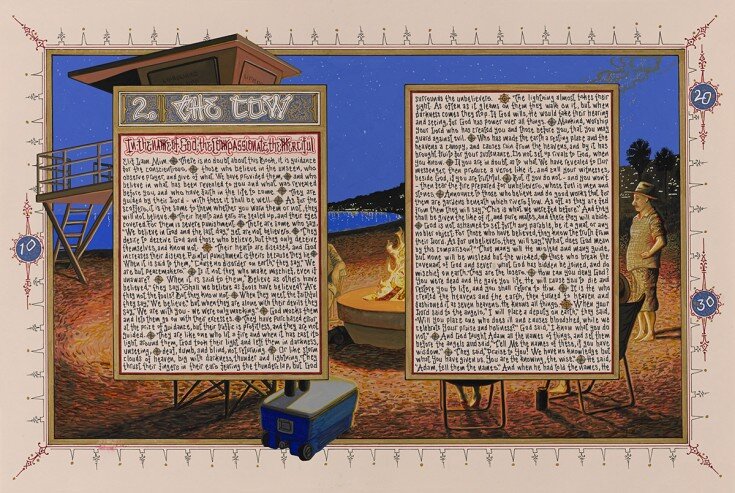

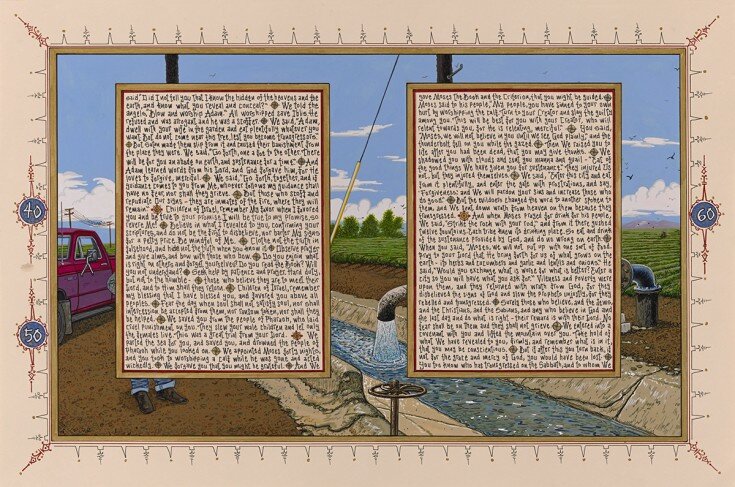

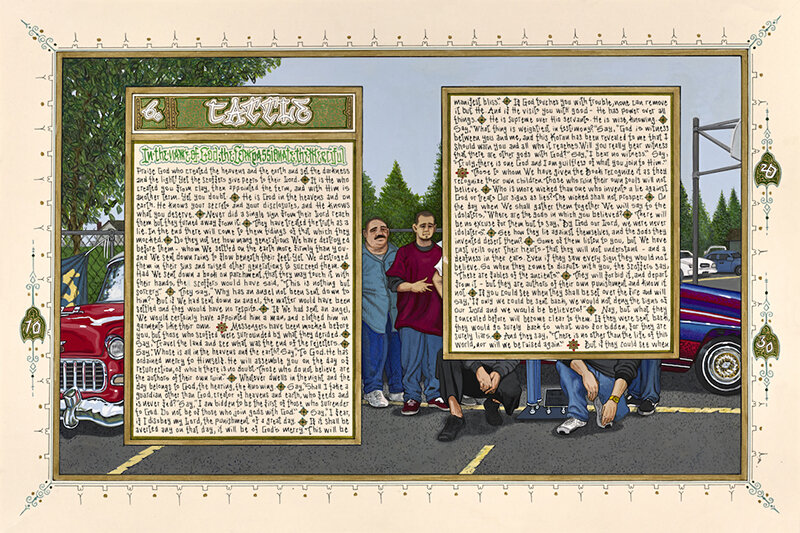

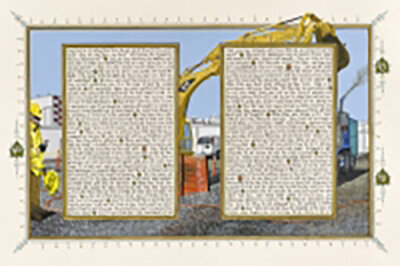

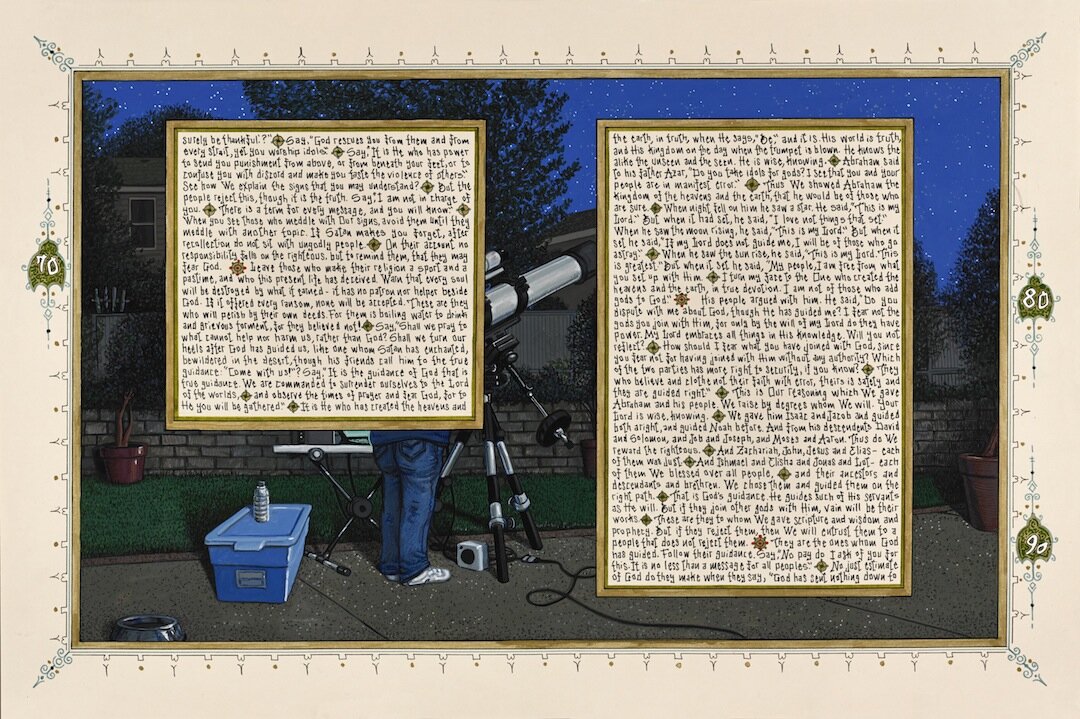

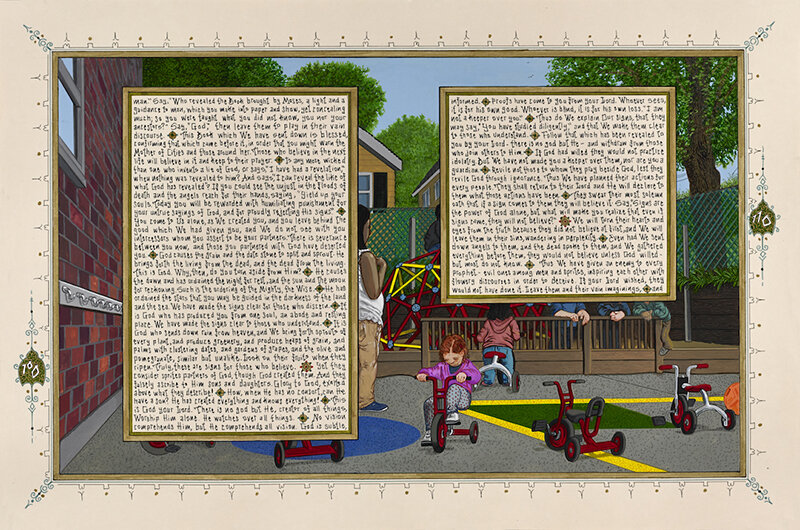

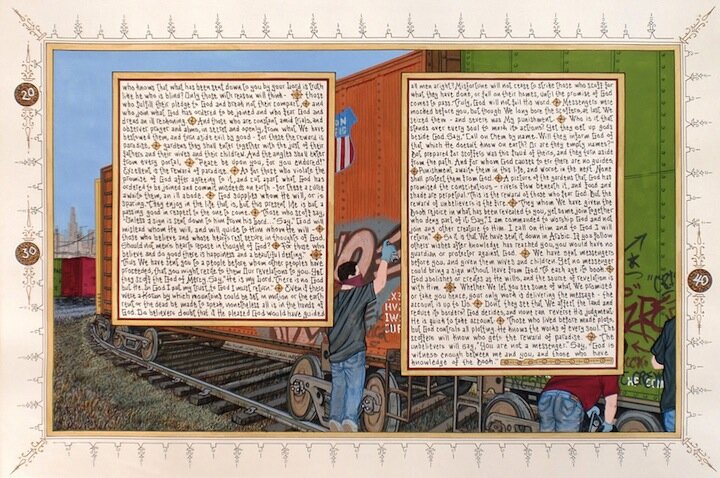

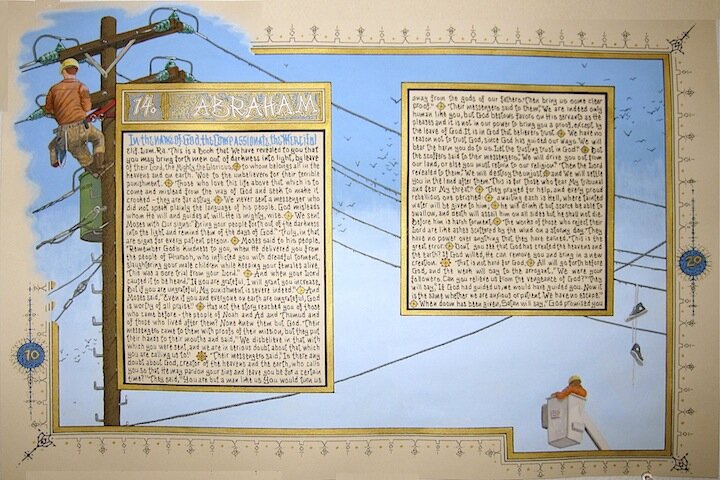

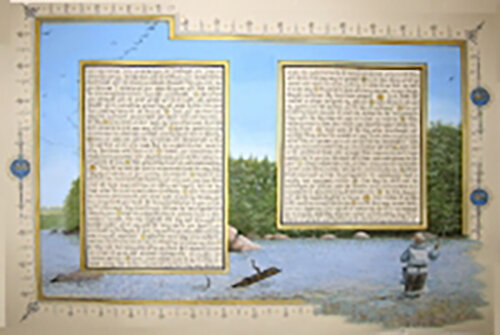

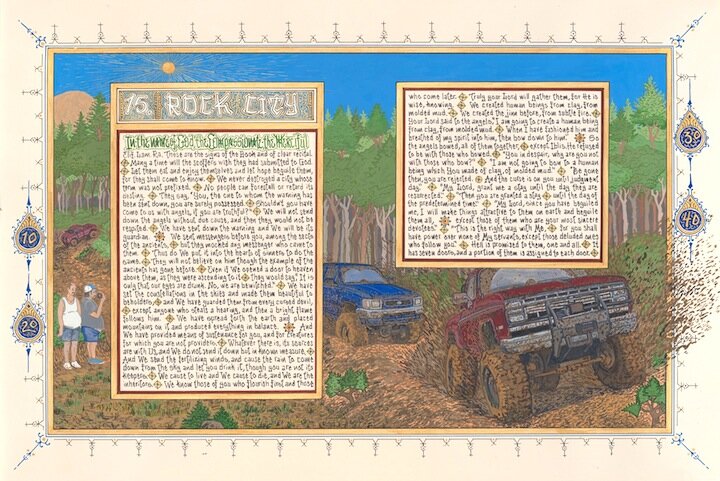

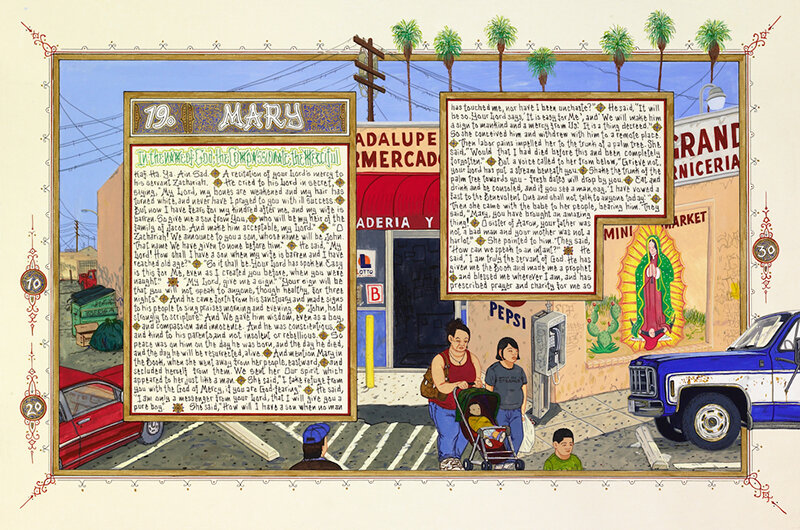

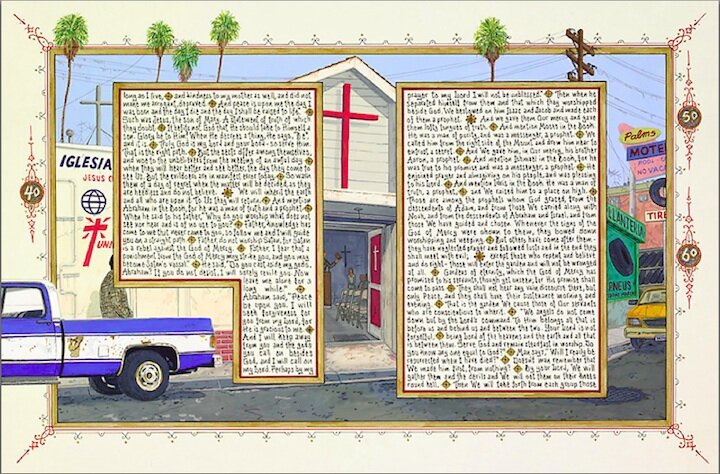

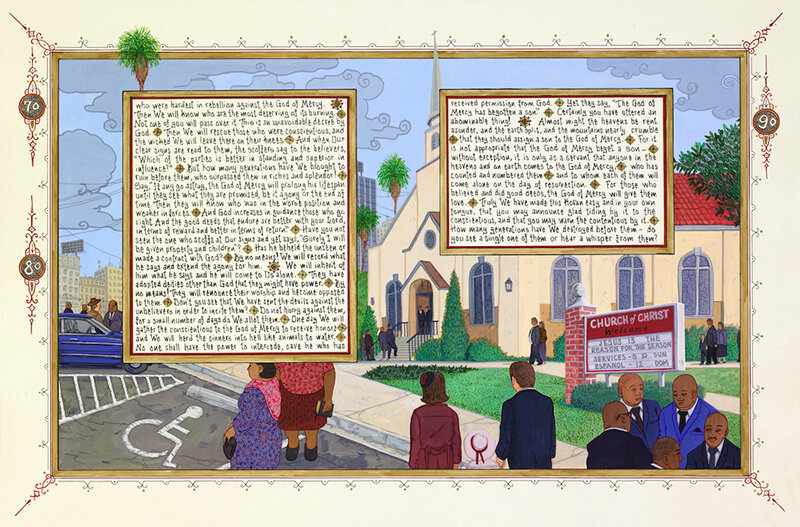

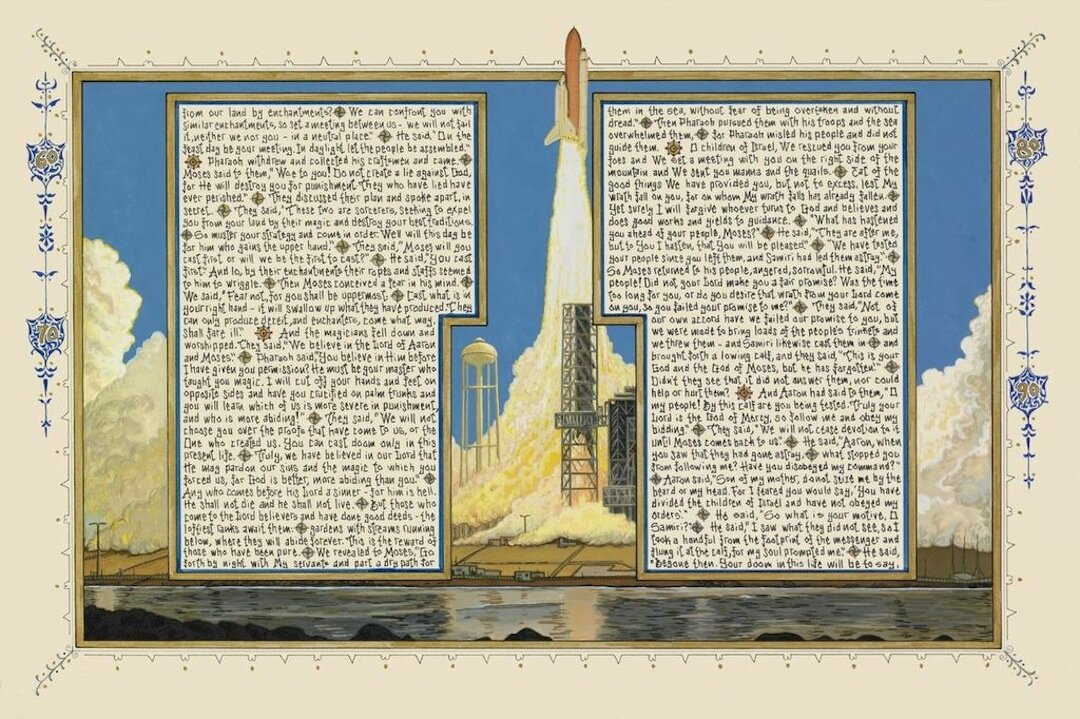

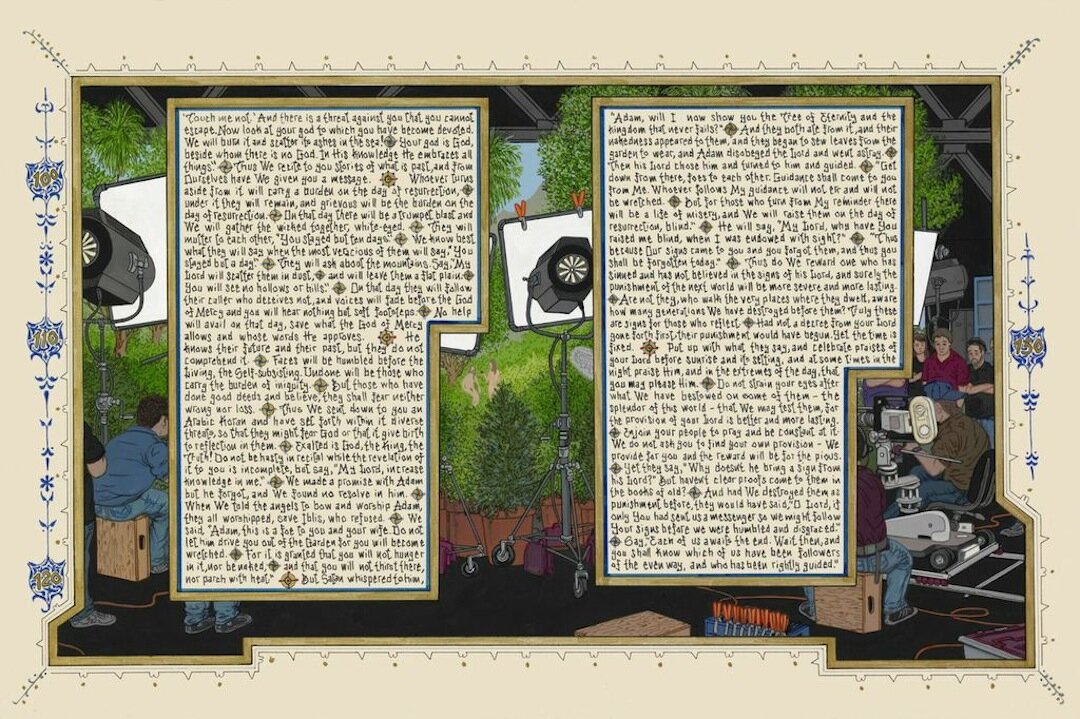

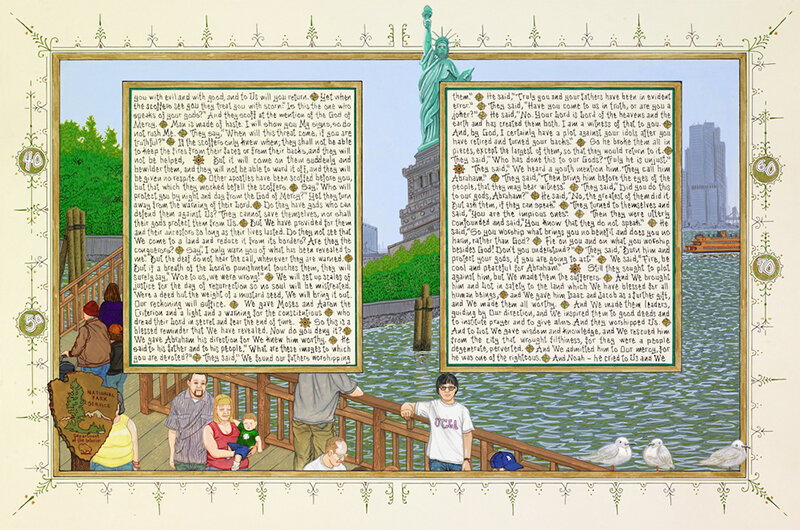

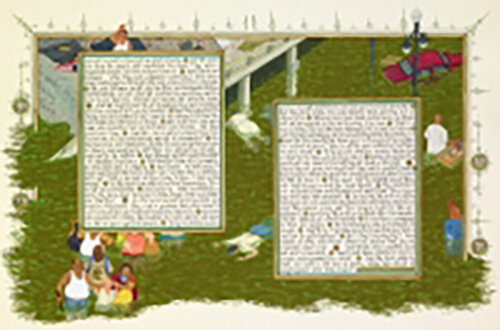

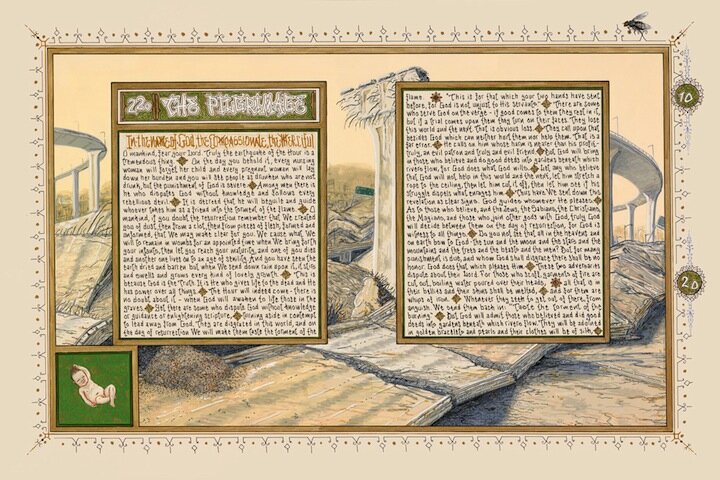

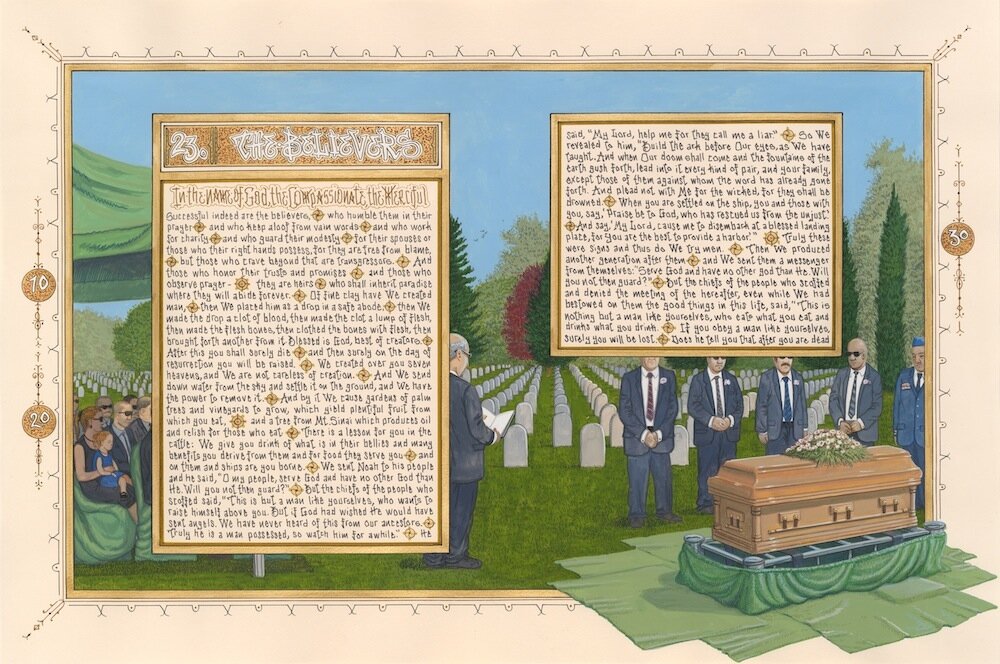

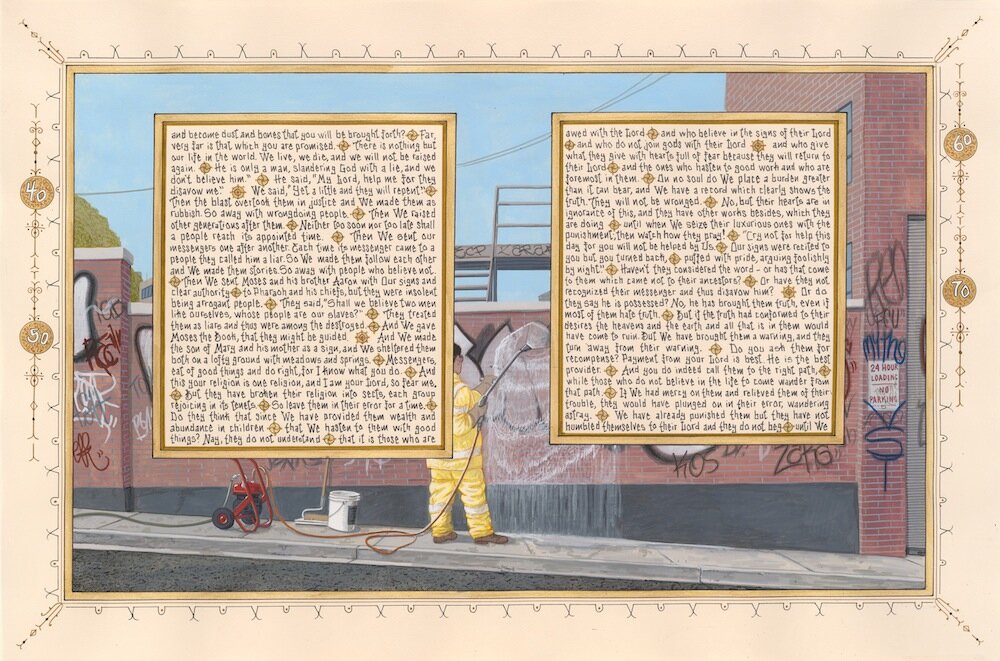

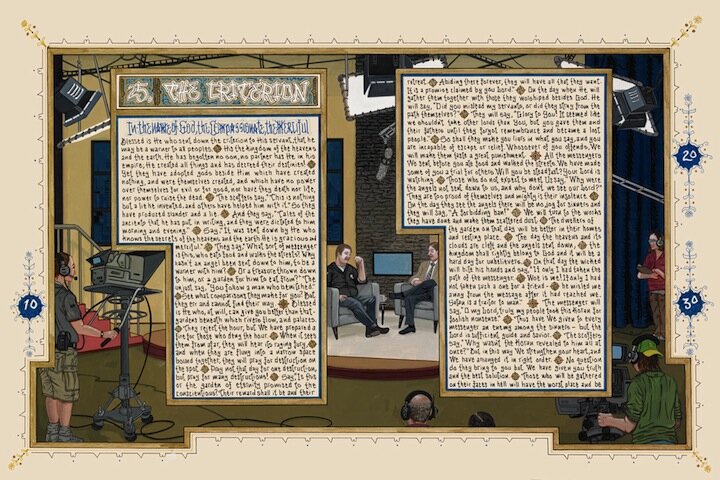

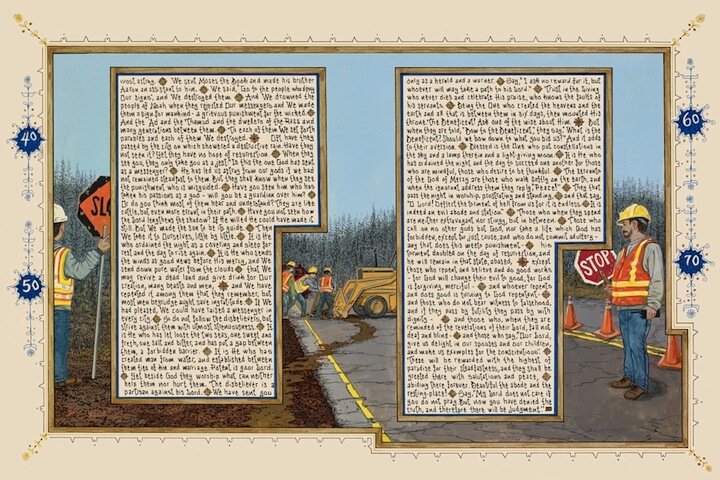

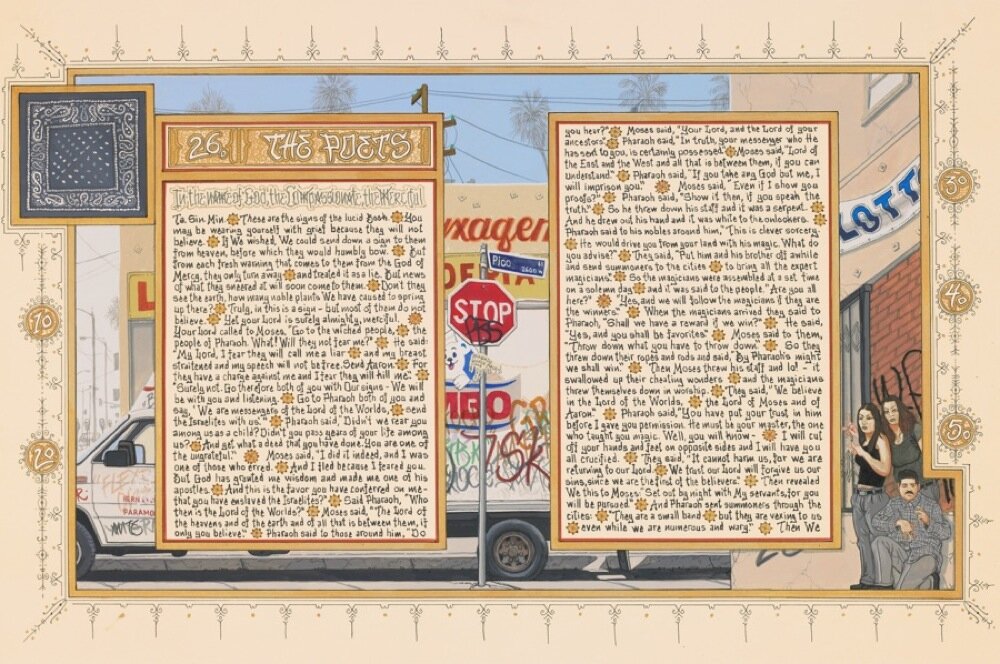

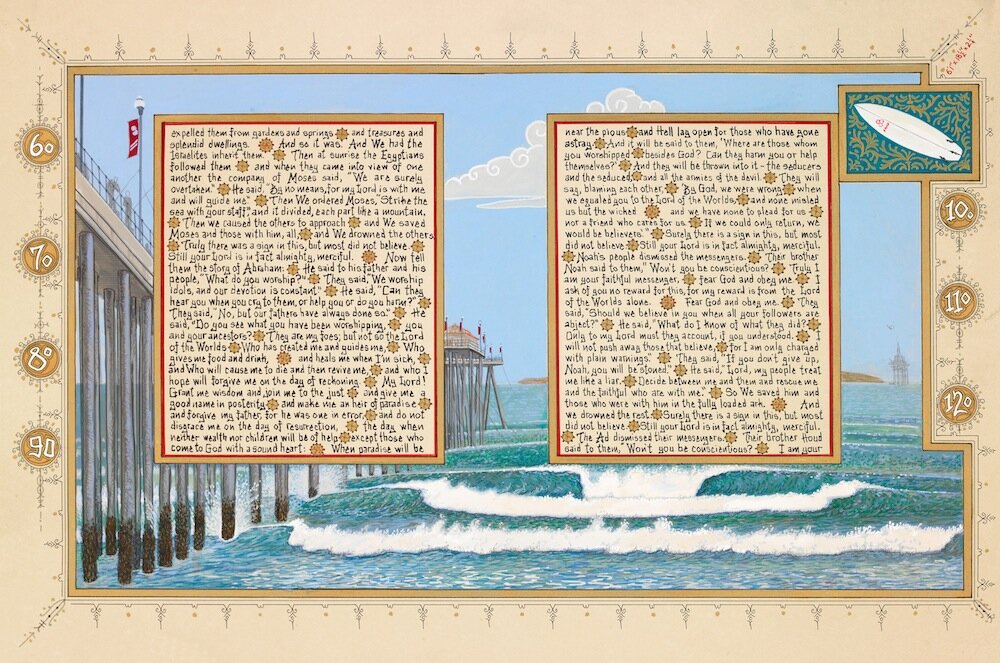

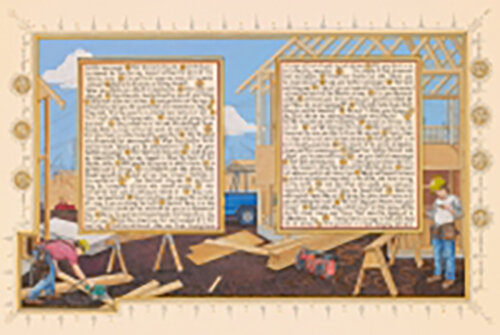

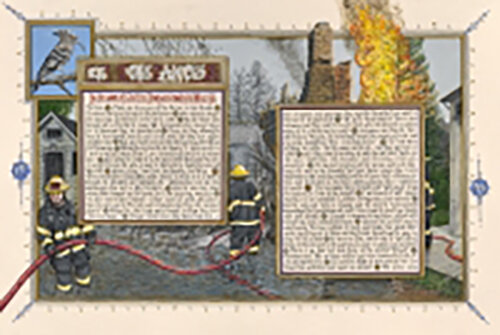

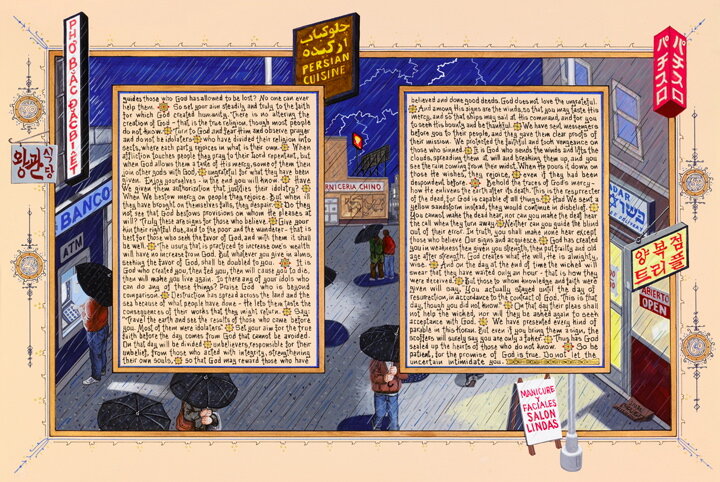

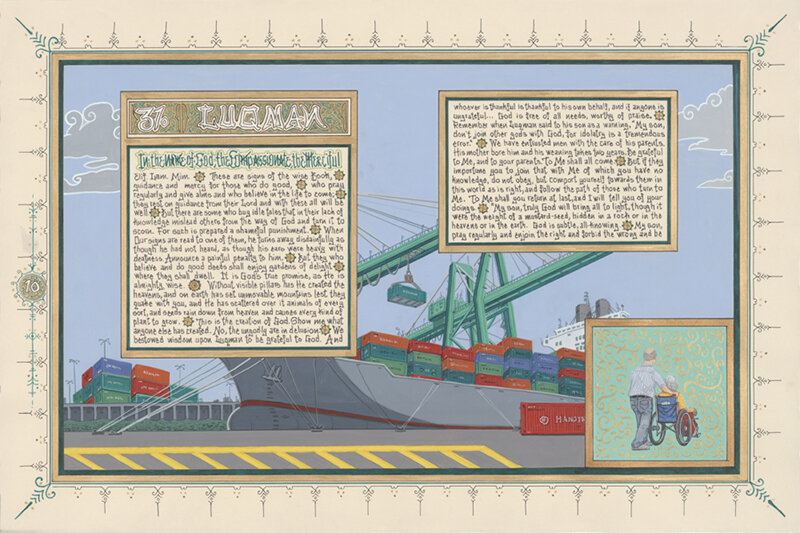

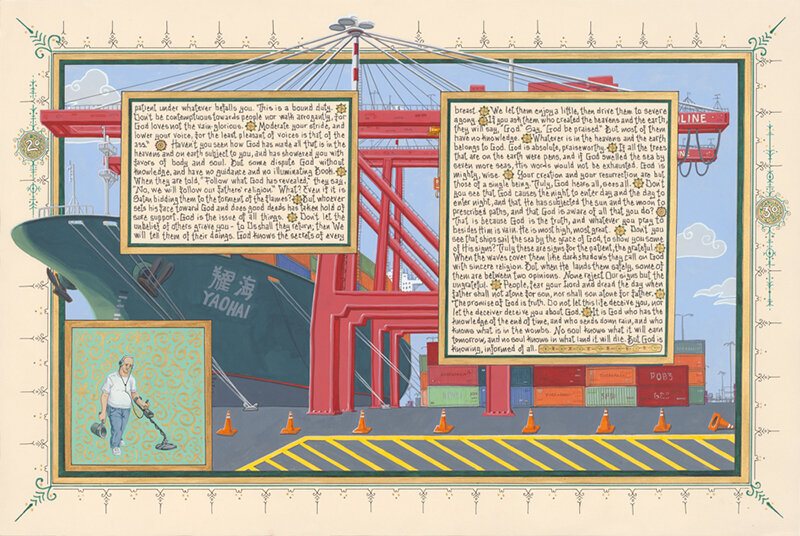

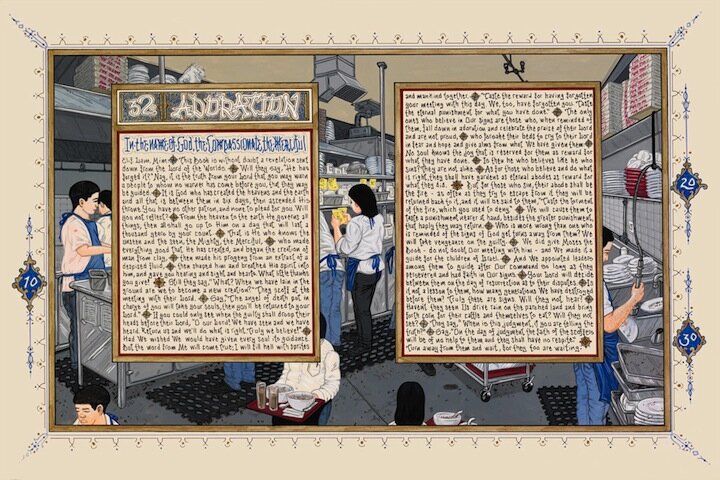

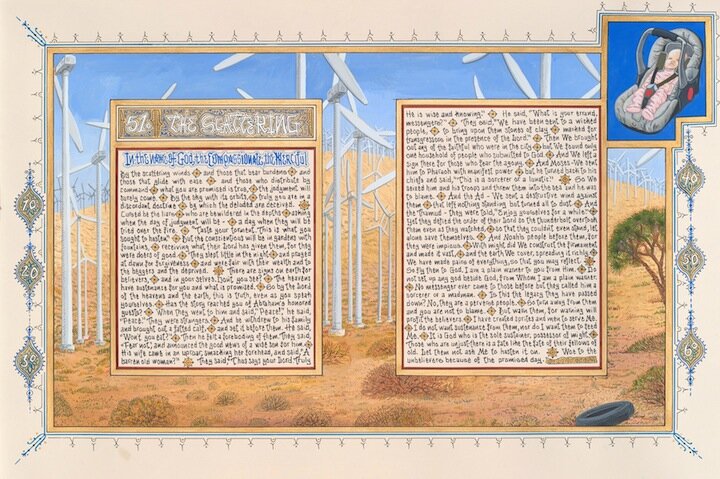

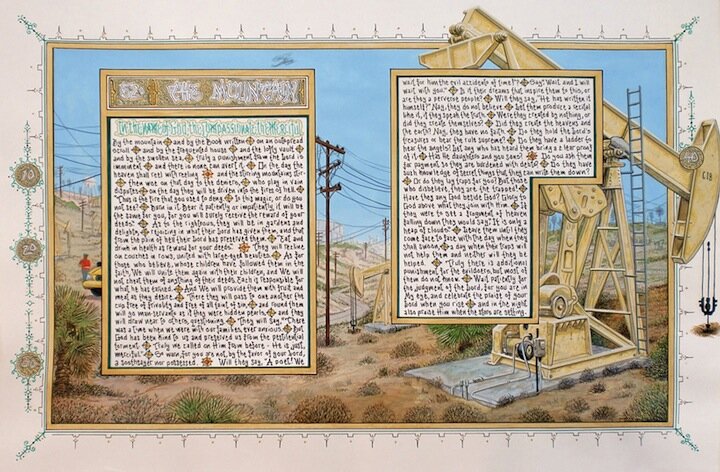

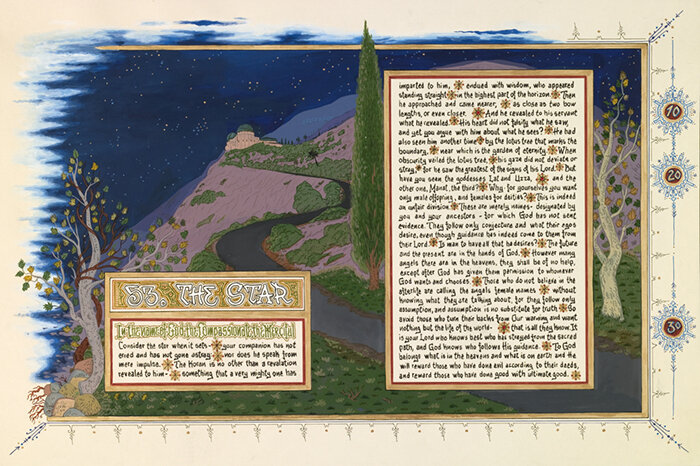

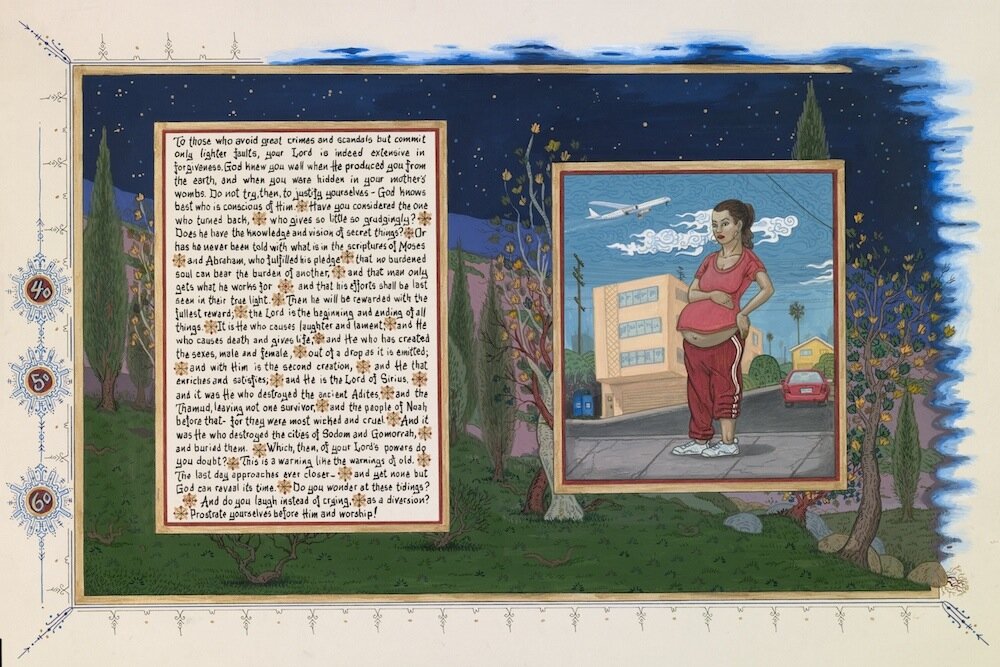

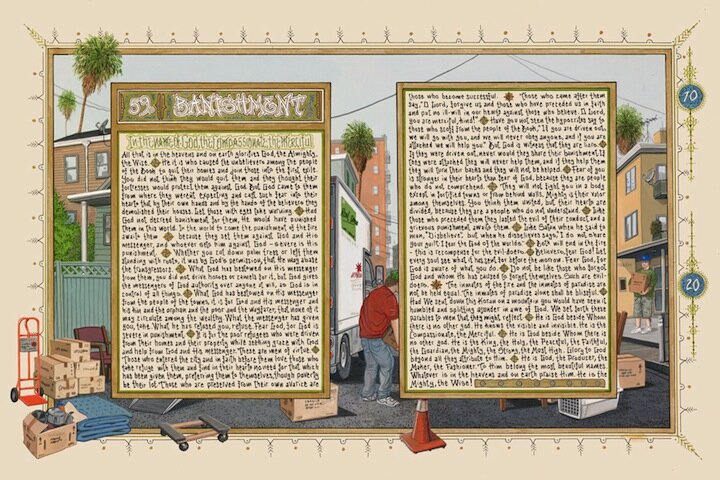

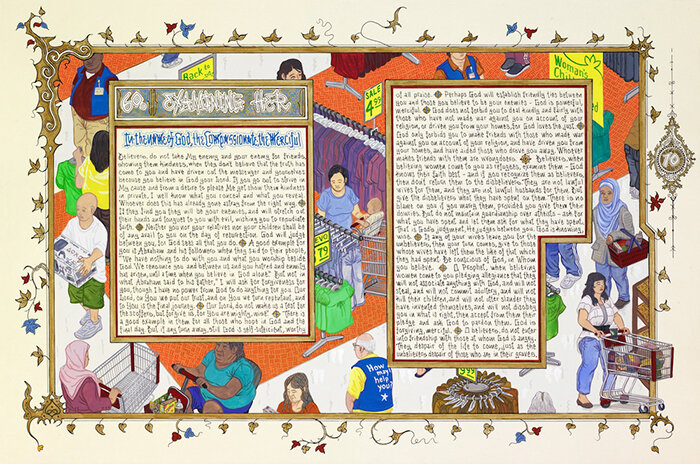

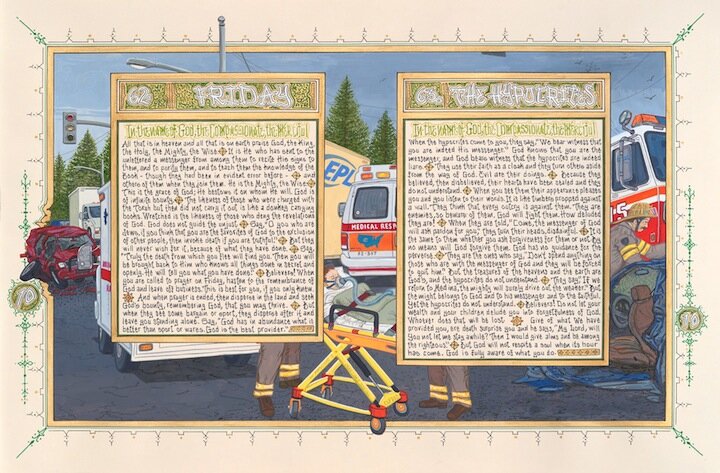

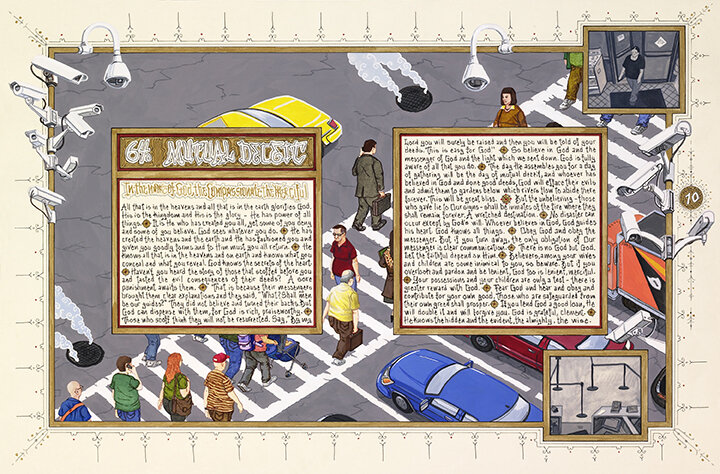

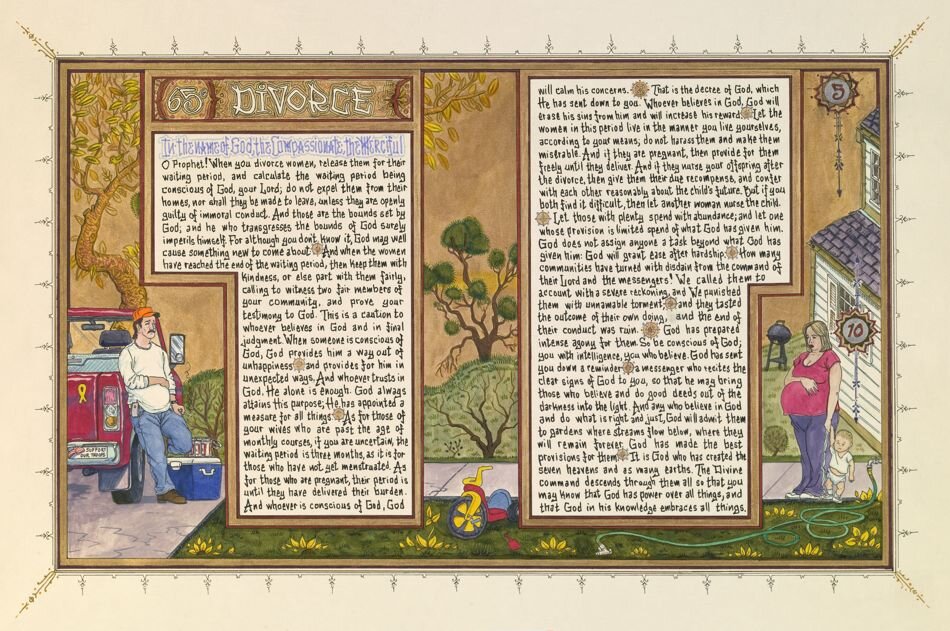

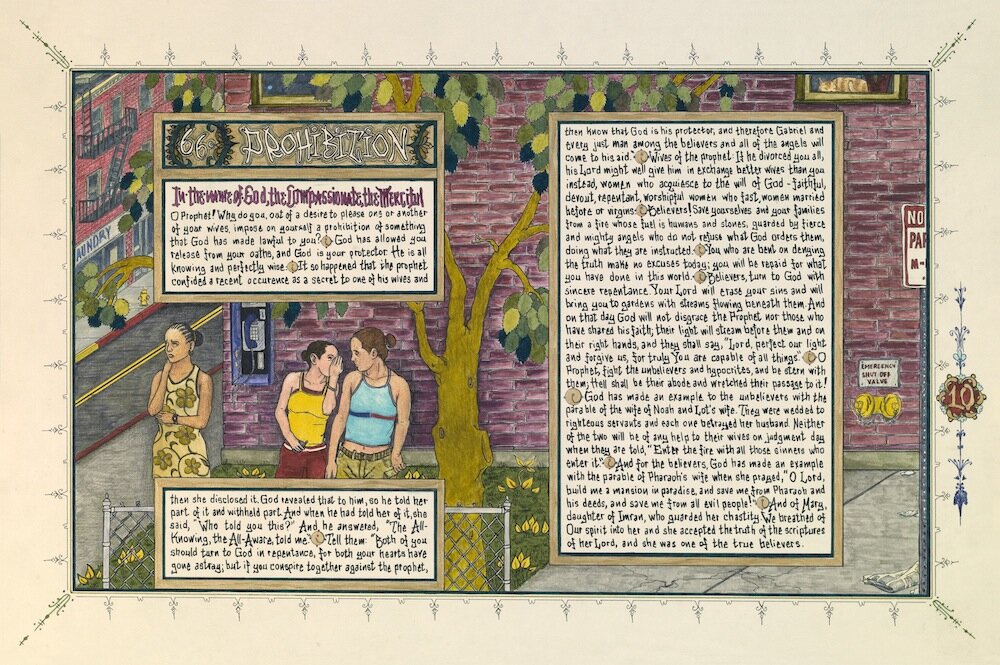

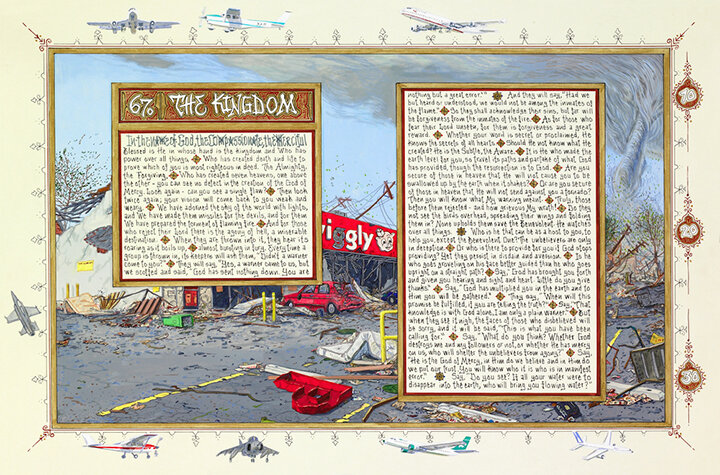

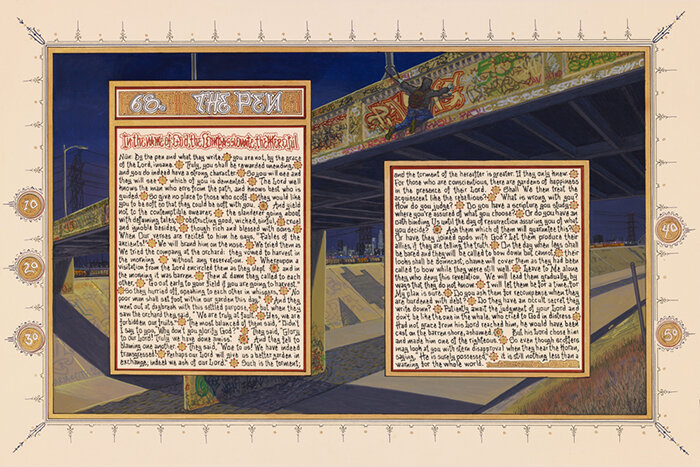

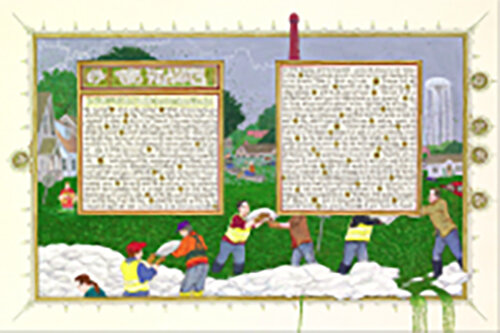

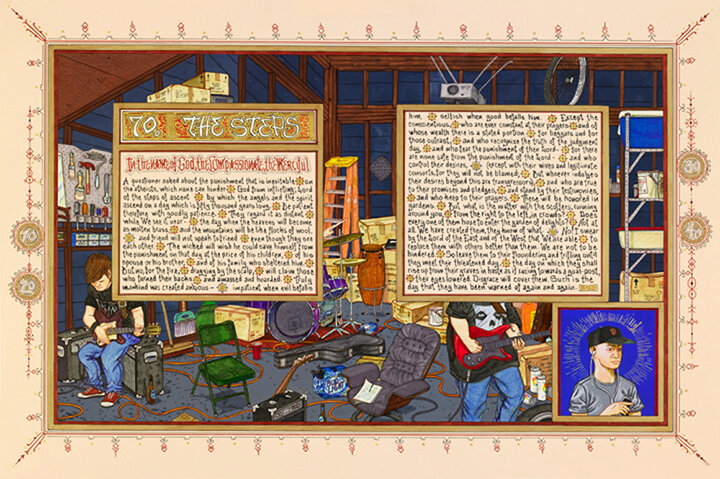

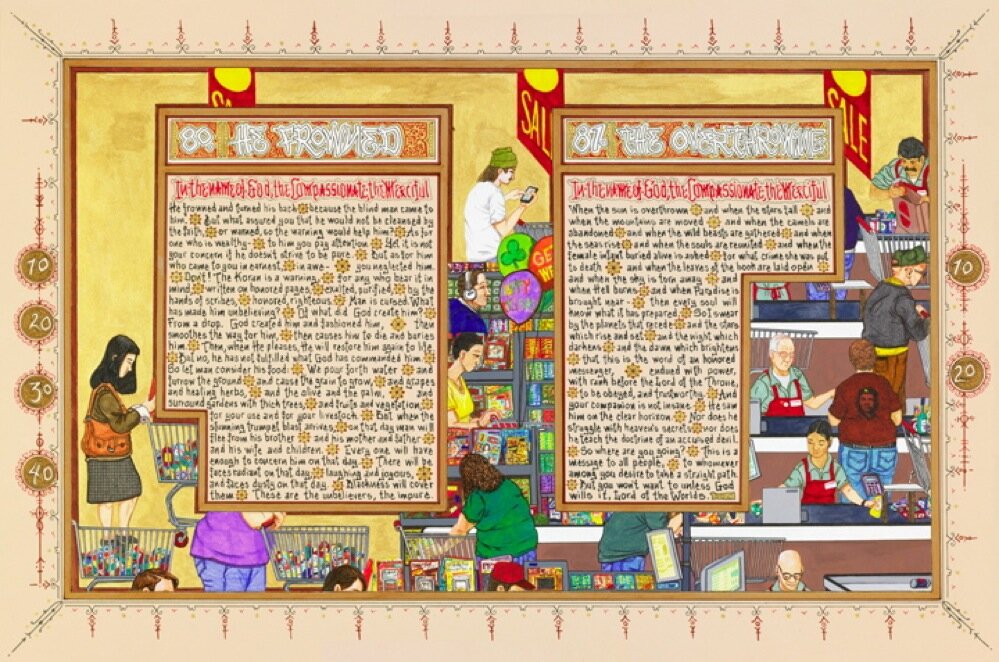

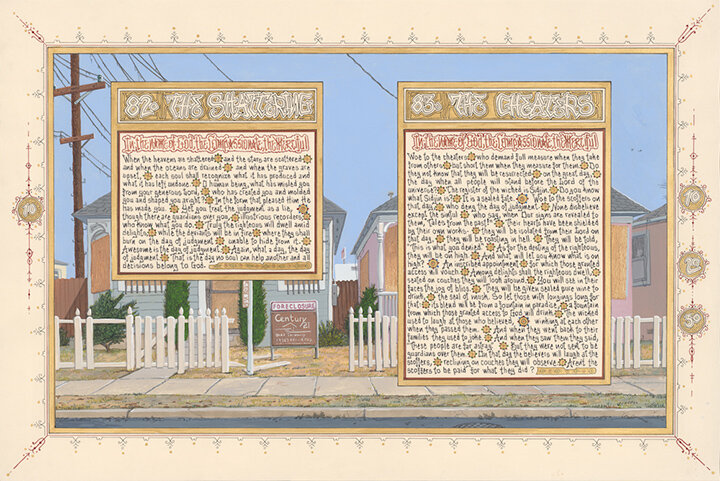

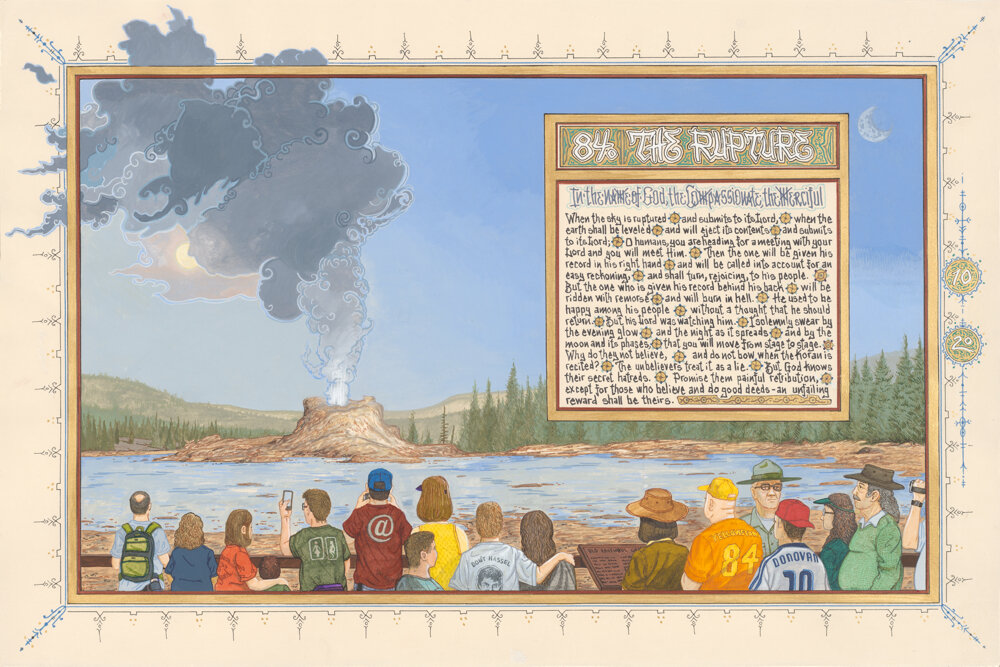

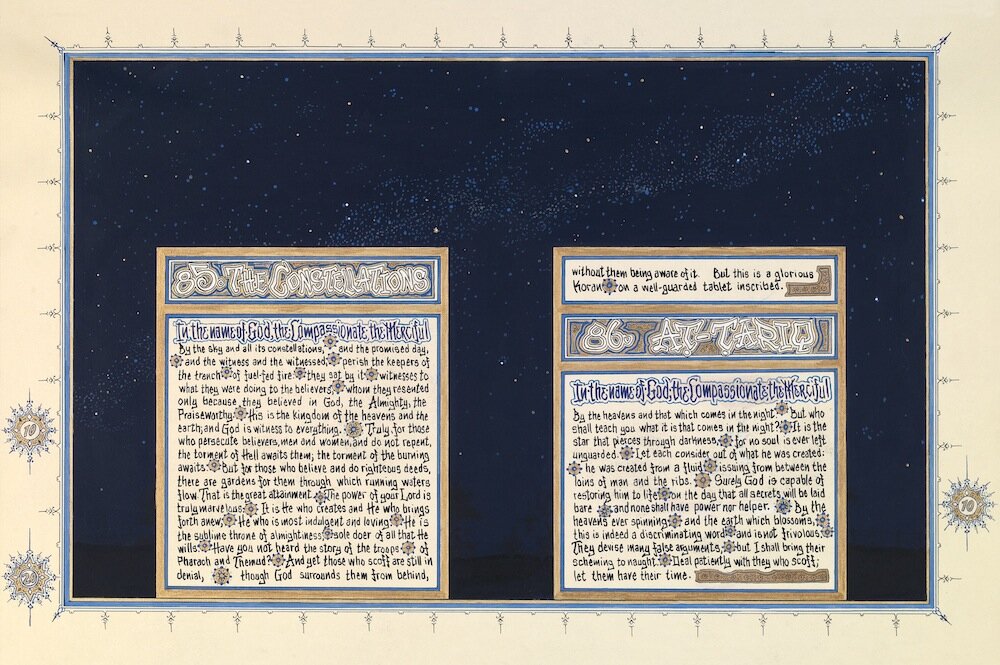

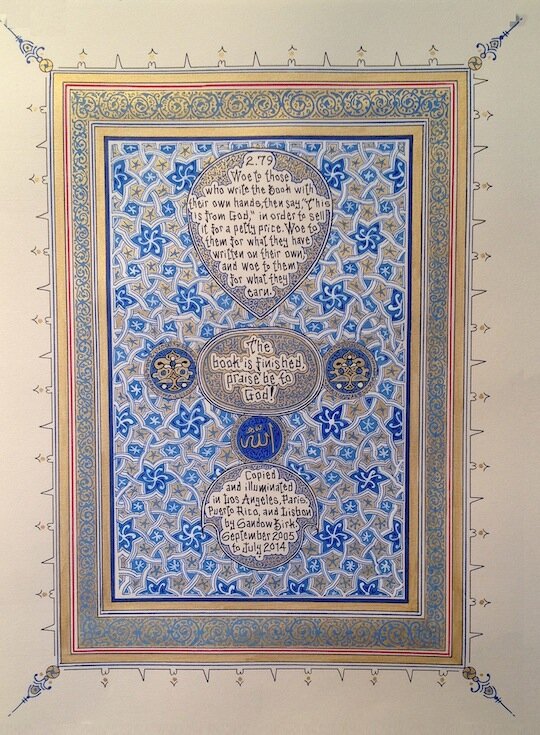

From that starting point, Sandow Birk spent the past nine years creating a personal Qur’an. Following the traditions of ancient Arabic and Islamic manuscripts, the artist hand-transcribed the entire English-translated text of the Qur’an as was done in centuries past – following traditional guidelines as to the colors of inks, the formatting of the pages, the size of margins and the illuminations of page headings and medallions marking verses and passages. His hand-lettered calligraphy uses an American tradition of writing - that of the street letters of urban graffiti that he finds around his Los Angeles neighborhood. Once each chapter was transcribed, the pages were illuminated with scenes from contemporary American life – investigating how the message relates to life in the United States today. Adapting the techniques and stylistic devices of Arabic and Persian painting and albums, the project blends the past with the present, the East with the West, creating an “American Qur’an”.

Background and research:

Over the past decade Birk has traveled extensively through the Islamic world, visiting several of the most populous Muslim nations as well as important collections of Islamic artworks. It was these travels, along with political events across the world, that inspired his initial interest in Islam and the Qur’an. During the course of the project his travels included repeated research visits to a variety of places, from the largest mosque in Africa to the remote Islamic outposts of Mindanao in the Philippines and the Andaman Islands of India. Among several other places, extensive research has been done throughout Morocco; at the Institut du Monde Arab in Paris while on a three-month residency at the Cité International des Artes; and at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, home to one of the largest and finest collections of hand-illuminated Qur’ans in the world. Further research was done at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries, and the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon.

Background – The Holy Qur’an

The Arabic word Qur’an means “Recitation”. The Holy Qur’an is a collection of the spoken messages from God as received by the prophet Muhammad through the angel Gabriel in numerous revelations over a twenty-two year period. The revelations occurred to Muhammad frequently from 610 CE until his death in 632 CE, and they were received in the western region of present-day Saudi Arabia near the cities of Mecca and Medina. After receiving them, they were spoken by Muhammad to his followers who wrote them down, supposedly verbatim, in Arabic. The various written verses were gathered together and arranged in the sequence of the present, universal form around 650 CE. The collection of these verses into 114 chapters, or suras, comprise the Holy Qur’an.

The 114 suras are not arranged chronologically, but (generally) they are arranged from the longest to the shortest. It has become common to number them and to label them with the city in which the revelation was received: either Mecca or Medina. The suras were not originally titled, but it has become traditional to title them. The titles now used are not necessarily titles that reflect the content or main concepts of the sura, but are rather usually a key word that helps identify the sura – often a word from the first sentence. This traditional naming of the suras is thought to be an aid to memory during oral recitations of the Qur’an.

The revelations were received by Muhammad in Arabic, and the true form of the Qur’an is therefore in Arabic. Any other language version of the Qur’an that does not also contain the text in Arabic is not considered a true Qur’an, since it does not contain the text of the revelations in the language in which they were spoken. The words of the Qur’an are considered to be the verbatim words of God Himself.

Each of the 114 suras but one begins with the words of the first sura: “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful.”

Over many centuries, before the widespread use of the printing press, calligraphers and illuminators produced versions of the Qur’an by hand. There were many basic rules that were followed in the fabrication of these codex. Basically, the text of the Qur’an was written first in black ink. (Since the older form of Arabic writing used in the time of Muhammad did not include diacritical points - punctuation or accent/pronunciation marks - the interpretation of the possible variations in meaning has been an ongoing debate in Islamic theology.) In later additions, punctuation and accent/pronunciation marks are added in blue and red ink, to note that they are not part of the original text. The pages were then decorated in elaborate illuminations of various degrees of complexity, often using gold, repeating patterns, and repeating symbols.

The text of the Qur’an is punctuated with elaborate medallions that signify the ending of each verse, and the margins of the manuscript usually include palmettes marking the 10th, 20th, 30th, etc. verses. Since it is improper to touch the text, the manuscripts usually have large margins.

Early Qur’ans were expensive to produce, elaborate, and beautiful. Frequently they were displayed on wooden stands to hold them for easier reading, and they were usually bound in leather covers with a flap and a thong to secure them, often with extensive gold stamping and decoration on the covers.

Birk’s project uses copyright-free English translations of the Qur’an from various authors. Following the traditions of Qur’anic manuscripts throughout the centuries, Birk worked to create unique artworks, each envisioned as if it were a two-page spread in a codex. Working steadily, the process involved the transcribing of the text by hand, using a hand-lettered “font” based on graffiti tagging, a particularly urban American writing form. The final project consists of 427 pages comprising all 114 Suras of the Qur’an.

All works are ink and gouache on paper, 16" x 24".